The True Story Of The Oscar Streaker

The True Story Of The Oscar Streaker

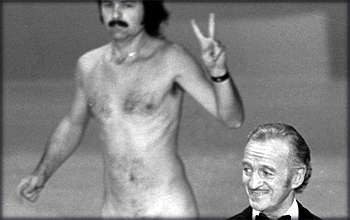

It was Tuesday night, April 2, 1974, and America and various other parts of the planet were knee-deep in the telecast of the 46th Academy Awards. David Niven (co-hosting with John Huston, Diana Ross and Burt Reynolds) was introducing Elizabeth Taylor, who was to present the Oscar for Best Picture, only to be interrupted by a young man running across the stage behind Niven. The man flashed the peace sign and kept running. He was wearing no clothes. And Niven noticed, and paused to acknowledge the amusement of the audience, and said something Niven-y and withering. And the live broadcast continued. (The Sting won!)

This event is notorious, and often repeated as one of the most scandalous moments of the history of the telecast of the Oscars. (Even by the Academy itself, as a “favorite Oscar® moment”.) This was an age when live television was pretty much the only avenue for instant pop-culture notoriety, as social media then was something that happened over water coolers and bridge tables, and ARPANET was still only dreaming of the age when it could be filled with an infinite number of cat videos. So a naked dude upstaging David Niven’s tuxedo? Very much an Oh my stars and garters! moment. And that is how the streaker, a man named Robert Opel, became notorious himself, and remains so, fodder for History-of-the-Oscars pieces and trivia in general, overshadowing the much more interesting trivial fact that an Oscar telecast was co-hosted by David Niven, John Huston, Diana Ross and Burt Reynolds.

Robert Opel became That Streaker Guy. This is a troubling fate for Robert Opel, because while he was perhaps the most televised streaker ever, he was much more than that.

At the time of the streaking, Opel was variously described as an unemployed actor with an eye on a stand-up comedy career and an advertising executive. It was a moment in the spotlight for him. He was later hired by producer Allan Carr to streak at a party for Rudolph Nureyev and Marvin Hamlisch (yes, really), and was even accorded a post-telecast press conference at the Oscars, just like the movie stars with their newly acquired statuettes. But was this a stunt in the sense of a stab at lasting fame?

From the preview for the documentary on Opel’s life (by Opel’s nephew, Robert Oppel, who spells his name with one more “p”) entitled Uncle Bob, Opel’s own explanation:

It all sounds very serious and very heavy, I guess, but part of it is to examine our attitudes about who we are and what we look like, and how important is it if I come to you this afternoon wearing green pants and this kind of shirt or I don’t have any clothes on at all? I mean, like, what does that really mean? How much information can you really transmit to each other on the basis of what you’re wearing?

He was 33 years old in 1974, slim with longish hair and a mustache (as was the fashion). He was actually employed as a photographer for The Advocate, and an advocate Opel was as well: an underground artist protesting various issues, frequently doing so while naked, both before and after the Oscars incident. He crashed City Council hearings, and he created a giant phallus costume that he wore as “Mr. Penis,” crusading against public nudity laws on the Los Angeles books.

But it was later, post-streaking fame, that Opel’s career as an artist and agitator blossomed, when he moved to San Francisco (finding LA an unfriendly place after being targeting by the LAPD for harassment in response to his frequent activism), later in the 70s. In San Francisco, Opel became notable in the nascent gay activism scene in SOMA, as a photography, filmmaker and publisher and the kinds of publicity/awareness stunts that shaped the movement. He ran an Anita Bryant Look-Alike Contest (Bryant being a noted anti-gay activist and orange juice pitchwoman at the time), and staged a mock execution of Dan White, the man who murdered Harvey Milk, with the executioner (Opel) dressed as “Gay Justice.” He appears prominently in both Gay San Francisco: Eyewitness Drummer by Jack Fritscher and Folsom Street Blues: A Memoir of 1970s Soma Leatherfolk in Gay San Francisco by Jim Stewart, two books about the birth of the gay protest movement in the Bay Area written by two members of the scene.

In 1978 Opel opened Fey-Wey Studios, a gallery devoted to erotic art which channeled the energy of the SOMA gay bars. Fey-Wey Studios, and Opel by extension, was instrumental in bringing the work of Robert Mapplethorpe to prominence. For a more indelible picture of Fey-Wey and the SOMA scene at the time, I refer you to this interview with photographer BIRON, a friend and contemporary of Opel’s:

With Robert Opel as its director, it was an incredible place just half a block down the street from the BLACK AND BLUE bar and the 8TH STREET BATHS — two institutions that attracted gay men to the area in droves and who would sidetrack to the gallery on opening nights. But when I said ‘director’ I was being sarcastic. Robert was more like a circus ringmaster who keeps things moving with one act after another. He had a lot of energy, a good heart, and to boot was quite handsome.

I miss those opening nights. The receptions were always fun with the usual booze and a good place to meet interesting people. Robert showed the works of Tom of Finland, Étienne, Lou Rudolph, Rex, Chuck Arnett, Domino, Charlie Airwaves, Rick Borg, Mark Kadota, Olaf, and The Hun, and other artists — all barely recognized as artists in those days even within the broader Gay community.

Opel’s career as a gallerist and activist was cut short in July of 1979, as he was murdered in the course of an attempted robbery. Two armed assailants demanded drugs or money, or they’d blow Opel’s head off. Opel declined, and the assailants weren’t lying.

It’s long been rumored that Opel’s streak across the screen was not necessarily a unilateral act of transgression by Opel, and that he may have had a co-conspirator or two. The facts that he gained access to the backstage area in order to stage the streaking, and that he was given a post-show press conference, give rise to the suspicion that the event was set-up by the producers of the broadcast, maybe to give the long-venerated institution a little jolt.

But ultimately, does it matter? Whether or not it was a work or a shoot, what remains is the still photograph from the telecast, with the pixilated nethers and the bemused look crossing the face of David Niven (a man who knew bemused).

The Niven-y thing Niven said (also rumored to be written before the telecast, in preparation for the planned streaking) was, “But isn’t it fascinating to think that probably the only laugh that man will ever get in his life is by stripping off and showing his shortcomings?” It might have been the only laugh Opel got on national television, but it’s certainly not the only splash he made. As a man dedicated to tilt at windmills we might consider quaint forty years down the road, Opel made a difference, in the gay liberation movement, and in the field of transgressive art. Says BIRON, “Uncompromising and unapologetic, he blurred the lines between art and life as he traveled beyond the confines of accepted behavior. Harvey Milk and then Robert Opel both killed within a few months.” The quote from BIRON is clearly the quote a person would opt to be remembered by, and yet, for the relatively short life of Robert Opel, the annual return of the Streaker at the Oscars! story is what remains.

Related: Your Ultimate Oscar Ballot Cheat Sheet for Nominated Shorts