How To Write A Love Letter

How To Write A Love Letter

by Carey Wallace

A love letter can stir more emotion than any other literature the human race has produced. But take one out of a lover’s hands and most of them become embarrassing, boring and absurd. They’re full of minor events reported as if they’re the opening skirmishes of a great war and small favors received with the thanks due a profound sacrifice. They’re riddled with inside jokes and lousy with clichés.

Love letters tend to fail as literature because love’s hallmarks are also the hallmarks of bad literature: lack of perspective, repetition, superlatives. But strangely, these flaws are part of how we measure a love letter’s sincerity. If we remove them, we remove the evidence of love itself.

In fact, some of the most profound failures among love letters are actually the products of great writers. And before we look at a love letter that works, it’s instructive to take a look at one that doesn’t, despite all its author’s talent: Robert Browning’s first letter to Elizabeth Barrett.

Browning was 33 in 1845, when he wrote the letter; Barrett, 39. The two of them had never met, although they had mutual friends. Browning wrote after reading Barrett’s first book of poems, which had catapulted her to fame. A year later, the two of them would marry, against the wishes of her family, who suspected Browning of being a social-climbing gold digger.

In the letter, Browning’s writing is undeniably gorgeous. He pays Barrett several ornate compliments. He deftly narrates two scenes: the effect of her poems on him and a moment, years before, when they almost met but didn’t. The scenes are vivid; the language is flawless. But the overall effect is of a man in the grasp of inspiration, not love.

“This is no off-hand complimentary letter that I shall write,” he declares in the first line. As the letter unfolds, his verbal pyrotechnics prove that thoroughly. But his self-consciousness also undercuts his claims as a lover. It’s not his facility with language that betrays him. Not everyone is struck dumb by love, and a master artist might be expected to produce great work in the thrall of it. But Browning’s best language isn’t spent embellishing the theme of his love. It’s spent embellishing his own observations: a lyrical departure on the difference between dried flowers and fresh, a long description after their failed meeting of his own regret, a catalogue of the ways he considered responding to her book:

Since the day last week when I first read your poems, I quite laugh to remember how I have been turning and turning again in my mind what I should be able to tell you of their effect upon me, for in the first flush of delight I thought I would this once get out of my habit of purely passive enjoyment, when I do really enjoy, and thoroughly justify my admiration — perhaps even, as a loyal fellow-craftsman should, try and find fault and do you some little good to be proud of hereafter! — but nothing comes of it all…

Ironically, the strength of his response to Barrett almost totally effaces Barrett herself. What’s important to Browning is that he loves her, that his “feeling rises.” He records his own responses with precision and intelligence, but he never applies that same imagination to Barrett. Years ago, they were unable to meet because Barrett was sick. But Browning’s account expresses no concern over her illness, no curiosity over what that time was like for her, and no curiosity about her current state. Barrett remains a shadow, offstage, while Browning lovingly details not her, but the emotion she provokes in him. Browning’s letter is not about Barrett. It’s about Browning. As a literary project, it’s a masterwork. As a love letter, it’s not only hollow, but grating.

In the grand scheme of things, this may seem like a small failure. Against war and disaster, how can it matter how any one lover addresses any other?

Love is one of the great engines of the world. The lack or desire for it drives us to greed and violence: war and disaster. In fact, our ability or inability to speak about love in these secret moments can have profound repercussions in our lives, and lasting echoes in the lives of others.

But if Robert Browning fails here, in the earliest stage of his great romance, is there hope for any of us? Has anyone written a love letter, and done it well?

One obvious contender is the author of Song of Songs, the great Hebrew love poem, some of the oldest and most widely read language on love in the world. In fact, it’s the limits of love letters that makes the longevity of Songs of Songs so interesting.

Love letters don’t give the illusion of eternity that some other literature cultivates. A love letter can seem tawdry and dated even to the author as soon as an affair ends. But Song of Songs has survived for thousands of years, which suggests that it contains language about love that has resonated through all that time.

How is it different from other love letters?

First, the lovers in Song of Songs talk about each other, not themselves. Romantic love, as we see in Browning, is often little more than a potent blend of imagination and selfishness. We compliment the other person by telling them how they make us feel, rather than praising who they actually are — often because we haven’t really bothered to learn who they are: we’ve been too busy enjoying how what we’ve projected on them makes us feel. Like Browning, we engage in the deeply satisfying project of self-revelation, and in return we tolerate our lover’s revelations — as long as they fit reasonably well into the fantasy we’re constructing. We make dramatic romantic gestures that have much less to do with what the other person might want than with our own cleverness and taste for drama.

But you don’t see any of this in Song of Songs. Instead of talking about themselves or their own feelings, the lovers talk almost exclusively about each another. The catalogues they make of each other’s bodies are vivid and carnal: “Your breasts are like twin fawns that browse among the lilies.. His body is like polished ivory decorated with lapis lazuli.”

They’re also, in contrast to Browning’s glancing references to Barrett, incredibly lengthy: at one point the bride begins a litany that begins at her lover’s hair and works its way through compliments to his eyes, cheeks, lips, arms, body, and legs, before returning again to his mouth. These lovers don’t delight in their own responses, but in the qualities of their lover, which they know in intimate detail. But the lovers in Song of Songs also know each other’s histories, praise each other’s accomplishments, call each other friends: after the long list of physical attributes, the bride concludes her praise with the line “This is my beloved, this is my friend.” Where Browning spends his language on himself, the lovers in Song of Songs spend their words on each other.

Second, the language in Song of Songs rings true. Almost the entire popular vocabulary of love is composed of promises so overblown that, viewed with any soberness, they’re actually lies, like Browning’s assertion that he loves Barrett’s verses “with all my heart.” This kind of hyperbole hasn’t disappeared since 1845. It’s still alive and well in popular songs: “I could never live without your love.” “Wild horses couldn’t drag me away.” But most of us learn through hard experience that lovers don’t really die when an affair ends, and that it doesn’t take wild horses to break up a relationship: the cracks and fissures in our own hearts are more than enough. And those popular falsehoods about love, repeated and disproven again and again, actually lead to a deep cynicism about the truth of love itself.

The lovers in Song of Songs never fall into this trap. Their language conveys great emotion with great vividness. It’s highly charged, and highly figurative. But instead of inflated speech, the writer captures his feeling in images that are commonplace and concrete:

Place me like a seal over your heart; for love is as strong as death, its jealousy unyielding as the grave. It burns like blazing fire, like a mighty flame. Many waters cannot quench love; rivers cannot sweep it away. If one were to give all the wealth of one’s house for love, it would be utterly scorned… See! The winter is past; the rains are over and gone. Flowers appear on the earth; the season of singing has come.

The writer of Song of Songs chooses ordinary things to name love: water, flame, song. This roots love solidly among ordinary things. But it also elevates ordinary things to the status of love. And because these ordinary things fill the world, when the writer of Song of Songs links them with love, he calls attention to the fact that the whole world is infected with everyday miracles, like flowers breaking out of the ground, that otherwise go ignored.

Song of Songs is also unsentimental. Popular language about love doesn’t just inflate love’s importance. It ignores love’s seasons. Love in a pop song solves all problems, cures all ills, rights all wrongs — but isn’t strong enough to withstand any whisper of imperfection. Song of Songs, in stark contrast, takes the vagaries of love head on. One lover is too tired to answer the other’s knock. The other abandons his lover to roam the city without saying where he’s gone. But these flaws don’t foreshadow the end of love. They’re just a handful of scenes from a love that is strong enough to admit the reality of trouble amidst a larger celebration.

In the end, both Browning’s letter and Song of Songs share one crucial characteristic: the fact that they were written at all. Too often we’re too busy, too embarrassed, too aware of our own limits to put our love into words. And it’s even more rare for us to commit those words to paper. But our hearts are both fragile and volatile, and life is hard. Lovers need words to cling to in the press and doubt of each day. The spoken word can help us in a moment, but the written word stays with us through a lifetime. Written down, an expression becomes both a record and a promise. And like the writer of Song of Songs, when we write a love letter, we don’t just record a season of our love. We make something that will help our love survive all seasons.

The good news, for all of us who are clumsy, or stupid, or even speechless in the grip of love: great love letters aren’t based on our cleverness or force of expression.

The best ones don’t depend on the quality of our language.

They depend on the quality of our love.

Related: How To Write A Love Poem

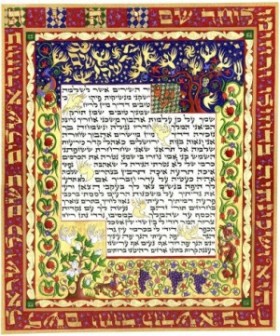

Carey Wallace is the author of The Blind Contessa’s New Machine (Penguin 2010). She lives and works in Brooklyn. You can find her blog here. Top image from Bright Star, via; Thomas B. Read’s portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning courtesy of Wikipedia; image of Song of Songs illuminated manuscript by artist Josh Baum via.