The Unfunded Art Project Inspired By Victorian Human Skulls

The Unfunded Art Project Inspired By Victorian Human Skulls

by L.V. Anderson

Sometimes, Kickstarter campaigns don’t meet their funding goals — but it’s not the end of the world! In this series, we explore what happens next.

Last spring, Jeanne Kelly, a visual artist with a background in forensic art, was finishing up her MFA at Parsons in New York. She found inspiration for her thesis among the 138 human skulls that make up the Hyrtl Collection at Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum. Jeanne wanted to find out what the former owners of those skulls, collected in the late 1800s, looked like. She selected eight individuals — including a tightrope walker who died of a broken neck, a famous Viennese prostitute who died of meningitis and a Russian man who died of self-inflicted castration — researched their lives, and imagined possible intersecting narratives for them. She decided to use 3D printing technology to create small replicas of each person and put them in dioramas to tell the stories of their lives and deaths.

While working a prototype of the diorama for her thesis, Jeanne created a Kickstarter to raise money to cover the cost of the very, very expensive 3D technology and other materials. After 60 days, Jeanne had gotten pledges for only $1,511 of her $8,500 goal.

L.V. Anderson: How much research did you have to do for this project — or was it mostly fictional based on your own ideas?

Jeanne Kelly: I started with the basic facts: the actual, factual concrete little bit of narrative that each individual had. Like, we know their name, where they came from, what age they were, what their occupations were, and how they died.

I think the real trigger for me was the tightrope walker and the fact that he died with a broken neck. And instantly when you hear that, you’re like, “Oh, of course, he fell.” He’s a tightrope walker, he died of a broken neck: he fell. Our brains want to fill in the story. And we’ll fill it in with the easiest path; we will complete that line.

And the thing that’s fascinating to me about doing this project was being able to work with that but also say, “And these other things.” One of the characters is known as a child murderer; she was executed for killing her own child. When I heard “child murderer,” before I knew anything else about it, and I just read before I visited the museum that there was a child murderer in the collection, the first thing that popped into my head was a creepy old man in the corner, and no, it turned out to be an eighteen-year-old girl. And then I started thinking, “What did that mean, back in the day?” and that’s when I started to look at the time period and the place and the factual information, historically, down to what people were wearing at the time, what the interests and the politics of the region and the time were, and that sort of thing to get a clearer idea of — okay, is this a child murderer in the way that we think of, or is this possibly a woman or a teenage girl who had an abortion and was executed for murder? All of these extenuating non-facts that fit into the story.

And the rest of it was purely fiction, was purely me trying to tie them together and making them up and making it interesting and breathing life back into these harsh facts and harsh realities of these people’s lives.

I wish I could hear all of your stories, because these characters — and I know “characters” is maybe not the right word, because they were actual people — but they’re just so interesting. Even the very small amount of factual information we have about them. Like the prostitute who died of meningitis —

Right?

— and the religious guy who died because he took off his own testicles — like, what the hell? I’m sorry, but that is ridiculous, and I want to know, how does that happen?

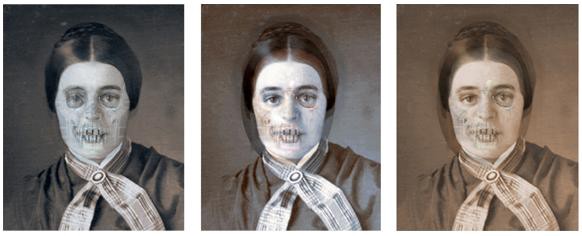

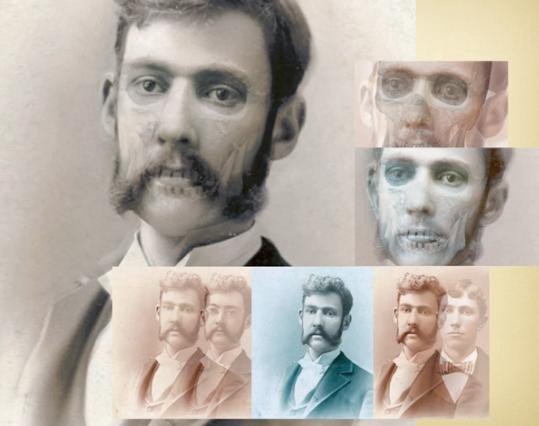

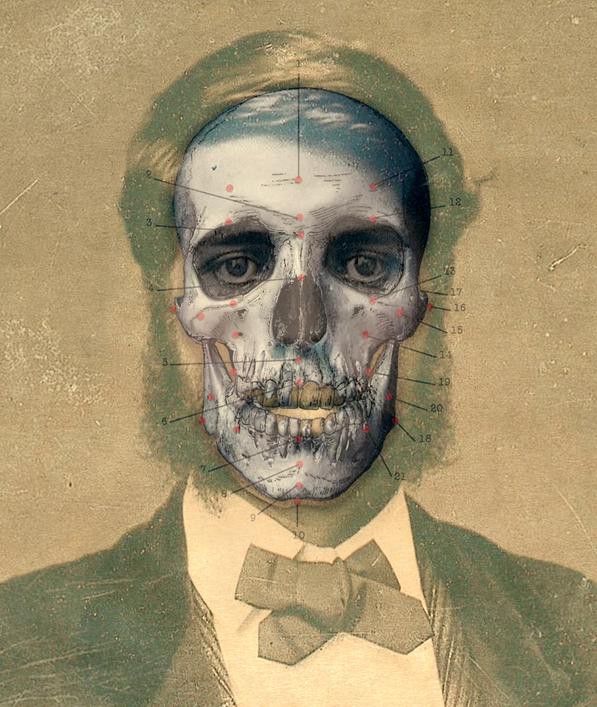

And why, and what in the world? And like the thing with the prostitute, she was the first skull that I actually went to, because when you see these skulls in the museum, in this bank, all these rows of skulls, her skull actually stands out as quite beautiful, as morbid as that may sound. I could tell that in life she was quite stunning. Her features are slight; her cheekbones are high; she’s very symmetrical in her features, which is very important when it comes to beauty.

I know nothing about forensics stuff — can you tell me a little bit about that aspect of it and about your background in forensic art?

It’s very scientific — there’s a lot of skepticism when it comes to, how much is it art, and how much is it forensic? When it’s done for legal purposes, such as when it’s done for identification of an individual that’s been found, and is unknown, it’s very rigorous in the application of technique and the application of data. When it starts getting into the artistic aspect of it, you really have to be careful not to take any liberties. So if you don’t know for a fact that the gentleman had a mustache or any facial hair, you don’t add it, because that’s the type of thing that would prohibit someone from recognizing [the subject].

So this project was not forensic in that aspect. It wasn’t legal forensics, and it was really freeing in that way, which went back and brought back also that research that I had done on the time period. Victorians love their facial hair! So I was able to have fun with that, and so my courageous cop has a big old Victorian police officer curly mustache. It just fits; it works with him. So there were liberties I took with these reconstructions that I would never take on legal forensic reconstructions.

http://player.vimeo.com/video/22275528?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0

This kind of diorama seems so old-fashioned to me, and yet the technology that goes into it was obviously extremely cutting-edge. In your art, is that tension something that appeals to you?

It does appeal to me, and I think for me this had to be this way; I had to let the time period that these people existed in dictate the feel of how their stories were going to be presented. So that was another big part of the research: What was visual storytelling in the Victorian times? And I looked at zoetropes and stereoscopes and all these different ways that people were exploring visual narrative at the end of the 1800s, and was just really inspired by the zoetropes and by these viewing mechanisms — basically you just turn this knob really fast and it makes a movie.

The digital aspect of it is probably where my heart lies right now. I work pretty much primarily digitally, and if I could get away with making everything digital, I probably would. But it doesn’t do the work any favors; there’s no justice in that, and it’s kind of selfish to do that, so I kind of loved being able to combine those two, like analog and digital, and have it work so well. Other pieces that I work on and other things that I do, I take the same approach. Whatever the project calls for, whatever is needed, is where I’ll go. So if it needs to be a sculptural, three-dimensional box with gears and lazy Susans and 3D printed figures, so be it; that’s what it’ll be.

How did you get involved with Kickstarter?

I really decided to do it because this is the kind of project that I could not have paid for out of my own pocket. I don’t have that kind of money. When I first started and was approved for it and put everything together, I had a big talk with a few friends about, “Let’s work this budget out, and what can we do, and where can we get free materials,” and that sort of thing. I think it was $8,000, the goal that I set, and the reason that I set it that low for this project was to get one box done.

I think for me, personally, the shortcoming of Kickstarter is that you almost have to be a little bit well known, even if it’s just within your circle of art or that sort of thing, already published, already have your foot in the door in order to get the donations flowing. Or you just already have to be connected. And unfortunately, I don’t have that kind of network. I tried, I really tried, but I’m maybe not the best self-promoter.

I know the feeling. But you did get $1500, which is something.

After doing Kickstarter for the Hyrtl, a friend of mine turned me on to a funding site called IndieGoGo. And it’s not as well designed and well presented as Kickstarter is. But the one thing they do that Kickstarter doesn’t — and I understand the reasons why Kickstarter does what they do, and they’re very valid — but IndieGoGo is, basically, when you make a pledge, you make a pledge, and if you have a goal, you have a goal, and if you don’t meet the goal, you still get what is pledged, and you still owe the pledgees what you promised as rewards. It would have been nice to have that $1,500 that people had pledged, and I would have been able to still fulfill my obligations in the rewards and the thank-yous that that would require.

I like the caliber of Kickstarter, but I don’t think I’m there yet. I feel like I could do IndieGoGo a couple of time and then move up to the East Side and go to Kickstarter.

Did you know early on that you weren’t going to get all the way up to $8,000, or did you hold out hope till the end?

I tried to hold out hope till the end. I had a lot of friends of mine who, like me, don’t really have the money to have donated directly to my cause except maybe $5 here or something like that, but I had a lot of people spreading the word. So I just kept this idea in my head that, “Oh well, once the word gets out there, once I get the right kind of exposure, things will really kick off and things will really start happening and I’ll start seeing the pledges being made.” I think it was really in the last couple of weeks that I realized, “Okay, plan B. This isn’t going to happen, so what do we do now?”

So what was plan B?

Well, plan B has pretty much been I attempted to fill out some grants, and it’s really difficult with this project because it doesn’t fit into the little cubbyholes that grants open in. So after I realized I was getting denied on several grants that I applied for, I basically had to be realistic.

So the project at this point has been pretty much shelved. I don’t really have the funds or the means to work on it or do anything more with it. The reconstructions themselves, the two-dimensional reconstructions, and the actual narrative are the two aspects that I can work on, and I have been, in free time, when I’m not trying to unwind from actually working on things, I have been working on reconstructions for the other four characters. I really, really want to see Geza [a herdsman who died of old age] done, and I really want to see Francesca [the famous Viennese prostitute] done. I just want to see what these people look like. And that’s where this project started: the very selfish, “I want to see what these people look like.”

So I’ve been working on that, and where it’s at right now is just developing the narrative and creating two-dimensional prints. There are prints and print variations at the Mütter for sale now in their gift shop, and I gave a talk at Observatory in Brooklyn and sold a few prints to some of the people that came to the lecture. And that’s where it’s at right now. As much as I would love to just devote a couple of years to building these and doing this, I just don’t see it as being realistic at this point. Especially now, truly understanding, having built one prototype, really understanding what the cost of this would be.

And you’re still in the MFA program, or did you graduate?

No, I graduated in May.

Oh, congratulations!

I graduated magna cum laude!

That’s great! What have you been doing since then?

I’ve been working with a team of people on a zoetrope that I think in September — September 14th to 17th — it was installed in Union Square. It’s part of the Arts in Transit program. It’s called Union Square in Motion, and it’s a digital linticular zoetrope.

What does that mean?

It’s a linear zoetrope, meaning instead of like the old-timey zoetrope where you spin the cylinder and you look through these splits and you see a horse galloping or you see something animated, what we’ve done is flatten that out. And I know you’ve seen them in subways, when you’re in the subway cars you’re going by and there’s this animation —

Oh, yeah. I love that.

So a linticular zoetrope, what it does is, digitally we can reduce the size of the image to 1.2 inches — it’s a manipulation to the image, and then it’s digitally projected through a convex or concave lens, depending on where you’re standing and which one you’re looking at. And it’s an optical illusion; it expands the image back out at you.

There’s a vacant concession stand there, and it’s been vacant for 14 years or something crazy, so we petitioned the Arts in Transit and contacted MTA and begged, and they saw what we were doing and said, “Sure.” And we did a Kickstarter! A new project.

Oh, wow! Was it successful?

It was indeed.

Wonderful!

We weren’t asking for as much; I think we got a little over $5,000, but it was just enough to purchase the monitors, because we needed nine televisions, and we had to build these boxes to go around them, and there were hard drives and flashcards and custom lenses put in front of the monitors to get all this done, but it was just enough to do that. Well, I shouldn’t say that; we then had to chip in a couple of grand to finish up the last bits, but the big chunk of it came from Kickstarter and Kickstarter funding.

So I’ve been doing that, and I’ve been doing a little freelance, mostly like digital design for websites and some branding for a friend of mine who’s opening a pickle store: gourmet pickles. They’re amazing pickles, too; I’m sure he’s going to do amazing. So yeah, just freelancing, and being happy with that.

Previously: The Connie Converse Album That Never Got Crowd-Funded

Was your Kickstarter unsuccessful? Want to talk about it? Send us an email with a link to your Kickstarter page at [email protected].

L. V. Anderson lives in Brooklyn and works at Slate. Images are copyright Jeanne Kelly.