Trinity

I.

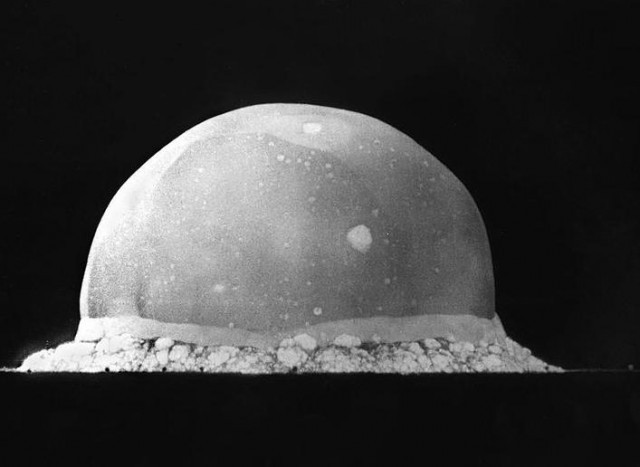

On July 16, 1945, the first atomic bomb test took place in the Tularosa Basin of the Jornada del Muerto desert near Socorro, New Mexico. Just three weeks later, Hiroshima and Nagasaki would be bombed: the only time nuclear weapons have ever been used in war. The test was code-named Trinity, and it forced a radical shift in the way that human beings came to regard their place on earth; from that day onward, for almost seventy years, we’ve lived in the uneasy knowledge that a very few people might gain the power to destroy all civilization — all life, even. The events of this day produced the chief wellspring of every kind of modern-day political and cultural anxiety, cynicism and depression. At that moment, humankind was forced to grow up, whether we knew it or not.

In Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, the bongo-playing, safecracking amateur magician and Nobel-prizewinning physicist Richard Feynman recalled his experiences at the Trinity test site. He was twenty-seven years old.

They gave out dark glasses that you could watch it with. Dark glasses! Twenty miles away, you couldn’t see a damn thing through dark glasses. So I figured the only thing that could really hurt your eyes (bright light can never hurt your eyes) is ultraviolet light. I got behind a truck windshield, because the ultraviolet can’t go through glass, so that would be safe, and so I could see the damn thing.

Time comes, and this tremendous flash out there is so bright that I duck, and I see this purple splotch on the floor of the truck. I said, “That’s not it. That’s an after-image.” So I look back up, and I see this white light changing into yellow and then into orange. Clouds form and disappear again — from the compression and expansion of the shock wave.

After the thing went off, there was tremendous excitement at Los Alamos. Everybody had parties, we all ran around. I sat on the end of a jeep and beat drums and so on. But one man, I remember, Bob Wilson, was just sitting there moping.

I said, “What are you moping about?”

He said, “It’s a terrible thing we made.”

For all his brilliance as a raconteur, Feynman leaves a great deal unsaid after that. The end of the subject chapter finds him in New York a short time later, having himself sunk into a terrible and entirely uncharacteristic depression, imagining the nuclear destruction of the city.

How far from here was 34th Street?… All those buildings, all smashed — and so on. And I would go along and I would see people building a bridge, or they’d be making a new road, and I thought, they’re crazy, they just don’t understand, they don’t understand. Why are they making new things? It’s so useless.

But, fortunately, it’s been useless for almost forty years now, hasn’t it? So I’ve been wrong about it being useless making bridges and I’m glad those other people had the sense to go ahead

And there the chapter ends. That a mind so eclectic and wide-ranging should kind of drop the ball at the very moment where some hard-core philosophical or ethical reflections would seem to be in order is a little jarring. Still more so this remark, made just a few pages earlier:

“[The mathematician John] Von Neumann gave me an interesting idea: that you don’t have to be responsible for the world that you’re in. So I have developed a very powerful sense of social irresponsibility as a result of Von Neumann’s advice. It’s made me a very happy man ever since.”

Feynman’s first memoir gives great care and attention to the idea of scientific integrity, to publishing whatever results we get, to “the truth” whatever it is, wherever we may find it and wherever it leads. The subject of moral responsibility, he barely glances at. But he would change his tune substantially, and only a few years later, perhaps in the wake of his work with NASA to discover and report the causes of the Challenger disaster. Feynman concluded his second memoir, What Do You Care What Other People Think?, with a lecture he first gave at Caltech in 1955, which contains a most thoughtful analysis of scientific ethics.

We are all sad when we think of the wondrous potentialities human beings seem to have, as contrasted with their small accomplishments. Again and again people have thought that we could do much better. Those of the past saw in the nightmare of their times a dream for the future. We, of their future, see that their dreams, in certain ways surpassed, have in many ways remained dreams. The hopes for the future today are, in good share, those of yesterday.

It was once thought that the possibilities people had were not developed because most of the people were ignorant. With universal education, could all men be Voltaires? Bad can be taught at least as efficiently as good. Education is a strong force, but for either good or evil. […]

Clearly, peace is a great force — as are sobriety, material power, communication, education, honesty, and the ideals of many dreamers. We have more of these forces to control than did the ancients. And maybe we are doing a little better than most of them could do. But what we ought to be able to do seems gigantic compared with our confused accomplishments.

Why is this? Why can’t we conquer ourselves?

It’s characteristic of Feynman that he seems content just to ask the question, let it hang there. This gives rise to the possibility that just the fact of the question might be teaching us more than any provisional answer could.

II.

Last week, an article by Alan P. Lightman appeared in Harper’s called “The accidental universe: Science’s crisis of faith.” Lightman is a physics prof at MIT, and also a novelist. He does a fantastic job of describing the cosmological freakout of modern physicists on being confronted with the possibility that our universe is only one among many, part of a “multiverse.”

Dramatic developments in cosmological findings and thought have led some of the world’s premier physicists to propose that our universe is only one of an enormous number of universes with wildly varying properties, and that some of the most basic features of our particular universe are indeed mere accidents — a random throw of the cosmic dice. In which case, there is no hope of ever explaining our universe’s features in terms of fundamental causes and principles.

This evidently makes a lot of physicists very sad, I guess particularly those who (unsatisfied with “42”) had hoped to witness the discovery of a definitive answer to Life, The Universe, and Everything. They are weeping like Alexander not because there were no worlds left to conquer, but because there are too many, an infinity-dwarfing number.

But maybe what we are coming to understand that the whole idea of “answers” is just lame, that we’ve been barking up the wrong tree entirely. Maybe we can face our uncertain future mindfully, like grownups. And even take some delight in the incalculable depth of the mystery of it. Of us.

It’s not the first time that the physicists have had to start over on a new basis of understanding, of course. And that necessarily means, for some, a lifetime’s efforts down the tubes. Also, it’s easy to imagine that the loss of such pretty conceits as the sphere of the fixed stars, or the geocentric model of the universe generally, or string theory or the be-all-and-end-all of Newtonian physics, must have caused confusion and pain to those who’d believed in those things all their lives. But it is also liberating to be freed of the burdens of certainty. The possibility of the multiverse being a true thing fills the receptive mind with pleasurable awe and humility.

In “The Value of Science,” Feynman explicitly described the abiding value of not-knowing:

With more knowledge comes a deeper, more wonderful mystery, luring one on to penetrate deeper still. Never concerned that the answer may prove disappointing, with pleasure and confidence we turn over each new stone to find unimagined strangeness leading on to more wonderful questions and mysteries — certainly a grand adventure!

III.

My grandfather died on my twenty-sixth birthday. I had been particularly close with Pipo all my life. He was the one person who never gave me any grief whatsoever, out of a large Cuban family very prone to grief-giving. To the point where one mid-summer afternoon at the age of fourteen, when my best friend’s diary was seized and read by her mother, and many of our various exploits became thereby known, and I arrived home to find this mother’s station wagon parked crookedly in our driveway and the door left wide open, and I knew that this could portend nothing good; when, after a time, I learned that the result of the terrific fuss kicked up by all these shrieking adults was that I should be sent to live in exile with my grandfather for a week or two, my only reaction was one of utter and blissful relief.

Pipo lived in a tiny and wonderful little house on the cheatin’ side of Long Beach. He was a gifted gardener who was devoted to his roses, his tomatoes. Such an exacting guy; you’d take him to the market and he would solemnly examine nearly every pear on offer before making his selection. He loved to cook and was so great at it. I lost my taste for Cuban chicken soup entirely after he died because it’s all just a sad, pathetic soup-shadow of my grandfather’s soup. This meditative, amused air he had about him. He was so composed, balanced and peaceful in his ways. And Pipo had the most fantastically attractive humor and generosity. I went to see him after I was first divorced, age of 22, having already been on the receiving end of a great deal of grief, such a rumpus you would not believe; I was just wrung out like an old dishtowel from the whole thing. I should have known better than to be expecting another lecture. He just laughed and said, “I hear you got rid of that skinny guy.” (Except in Spanish. Pipo never learned to speak English, except for baseball.)

When he died it was like losing an anchor of a certain indefinable kind and I knew I would be just drifting for a long time. There were so many people at his funeral. And here we turn to the subject of this story, because Pipo was, nominally, a Catholic, but like most in my family merely a cultural, one might say secular Catholic, not at all an observant, religious one. He would go to Mass for a wedding or a baptism, but I never saw him receive communion; he distrusted priests and the machinery of the church intensely, in his quiet way, but never would he have broken with Catholicism formally. Such a thing would have been unthinkable.

By the time of his death I had broken with the church myself, a positive break, and I had all a young person’s “intellectual” certainties, complete with a magisterial contempt for all the superstitious mumbo-jumbo of religious rituals. But when you are twenty-six and really quite unmoored and one of the only people you’ve ever really trusted has just disappeared off the face of the earth, and there are all these strangers and distant relatives kind of surging all over you and explaining how well they knew him and how much they cared, and they are just all in your face and trying to get near the Center of the Grieving. All you want is for them to go away, because you cannot talk to one more person who wants to watch you fall to pieces, in what seems like a downright ghoulish and even peeper-ish manner.

But in advance of a Catholic funeral a rosary is read, which, a rosary is this necklace of beads and each bead signifies a prayer. But it’s just the same two prayers, over and over: Aves, or Hail Marys, and Paters, or Our Fathers. Ten Aves, one Pater. You do this fifteen times. And during each decade of ten Aves you are technically supposed to be contemplating a specific joyful, sorrowful or glorious Mystery, such as the Annunciation, or the Resurrection; there’s a set order to it… well anyway, there is all this stuff you are meant to be thinking about. But who is to know what you are thinking about as you repeat these words?

And they’re really easy words to remember and repeat because you’ve known them all your life and magically everyone gets right out of your face and it’s quiet in your head, finally. There is murmuring like doves, a rustling stillness, and suddenly instead of hating on all these people to an almost unbelievable degree I realized it was my grief, sadness and rage that had been making me feel so uncharitable, and that I really was (and not just “should be”) grateful to these people (any of whom might indeed have known and loved my grandfather as much I did, at some stage in his long life) for coming all this way to participate in this sad occasion with my family, when they could have been home making pancakes. That was the first time a religious ritual had really worked for me — like a charm, in the event — and though it didn’t alter my essential lapsedness I felt a pang, that I had been so summarily dismissive about this thing that had, clearly, its uses. For a lot of people.

Never again did I express scorn or open disbelief in any kind of spiritual practice, after that day. I’m in no way suggesting that the comforts of religion will work for everyone; they won’t ever work for me; I am by nature too skeptical even to embrace atheism. But all peaceful strategies for dealing with our pain are to be respected, from however afar, I strongly believe.

Something more than that happened, too. The switch flipped for me conclusively into an attempt at adulthood, on that day. I set my mind in such a manner as to try to worry only about giving offense, and never about taking it; to think about honoring my obligations to others, rather than the other way around. To take care of others, rather than to be taken care of. That means giving up the innocence and trust of a child, the comfort of knowing that someone wiser and better than you is going to come and make you soup. Well, the day comes when you must cook your own soup, and that is in a way a sad thing, and in another way a mysteriously liberating and exhilarating one.

It’s a similar way of thinking that is possible, and even suggested, by the legacy of June 16, 1945; a submission to the few inalterable realities we must face as we head on into the whatever is to come. Forgiveness of what is past, of the mysterious and unknowable paths of others, a willing recognition and shouldering of our shared burden. The only certain knowledge being how little we can ever know.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.