The Struggle For The Occupy Wall Street Archives

by Michelle Dean

The story of the Occupy Wall Street Archive starts with Jeremy Bold, so we might as well too. When Hollywood decides to cash in and make its OWS movie, central casting could do worse than work off a picture of Bold — he has a dark goatee and black plastic-rimmed glasses. He has a “protest name” — Jez. He’s in dark, long-sleeved t-shirts and jeans whenever I see him, hair askew, a well-worn nylon backpack slung over one shoulder and a scarf not infrequently tied around his neck. In other words, he looks like any number of people you might have seen at Zuccotti Park. Jez is 27 and originally from North Dakota.

Though he’s been involved in Occupy Wall Street from its inception, Jez isn’t a career leftist. His current part-time day job is as a subject librarian in philosophy, at NYU’s Bobst Library — the impulse to collect and curate comes naturally to him. And Jez had an idea that was deceptively simple. He’d collect and catalogue all the signs and pamphlets and newsletters and odds and ends of political art the protests have generated. But preserving all of those for posterity turned out to be, as with all things Occupy Wall Street, more complicated than anyone could have foreseen — not least because the movement itself would have trouble seeing the value of an archive.

You are also welcome to read this later with Instapaper.

An example of how Jez talks: The first time I asked him to explain his motives for starting the archives, he grinned and said, “The idea came from a number of places, and I’ll try to make it as simple as possible, as succinct as possible.” He paused and then took a deep breath. “There is an essay, or an interview with Jacques Derrida, which occurs in a book called Philosophy in a Time of Terror.”

My “okay” on the tape sounds decidedly skeptical.

But as Bold continued his explanation, he drew on an idea that doesn’t require Derrida’s guidance to understand. Put simply, it’s that the history-defining moment has that same old clichéd quality of pornography: you know it when you see it. However, in the moment it can be hard to grasp the moment, so to speak. You may know that “something happened,” but you might not know what it is.

Bold said he had this sense early on in his involvement in OWS. And inspired by a presentation he’d seen at NYU about the collection of artifacts after the September 11th attacks, he decided to get serious about collecting immediately. He told people he knew in the movement to save their writings and signs. He began carrying stuff home himself.

But — and this he says he took from Derrida too, who wrote a book called Archive Fever — he thought it was essential, if the movement wanted to have some degree of control over how it was recorded and interpreted by historians, to collect their own documents. “So I was like, we have to have our own house, and if we’re going to talk about creating our own history, doing all this stuff ourselves, we have to have our own archives. So I was like, all right, let’s do it.”

When I first met him, Jez was referring to the project as the Occupy Wall Street An-Archives. He had also, of course, started a (sporadically updated) tumblr of that name. But when I asked him if he identifies an anarchist he almost laughed.

“The thing is, I’m not! I never even identified as an anarchist until this thing, where I was like, oh, is this what anarchism is?” he says, his voice rising to a self-critical falsetto. “I guess, maybe I’m an anarchist?”

That ambivalence about anarchist politics, let alone activist politics more broadly, was to become a general theme of the Archives project. Maybe that was inevitable. File boxes and acid-free manila folders don’t usually take center stage at a protest. Everyone’s eyes are on the political ideals, not the filing cabinets — and justifiably so, at the time. Worrying about the archives can seem strangely beside the point — until that is, you read the historian’s account, and can barely find yourself in its reflection.

***

On the evening of October 9th, Jez spoke at a general assembly meeting in the park. He announced he’s been collecting for the movement’s archives. The minutes record him as appealing to the example of the Greeks.

One of the people at the general assembly that day was Amy Roberts. Amy is studying for her master’s at Queens’ College’s library school. She is tallish and slim and has pin-straight, dirty blonde hair. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen her wear makeup. Amy is from Wisconsin originally; after an aborted first attempt at college, she spent a few years in St. Paul, Minnesota. She was involved in a socialist group there, and started working at a meat plant as part of an effort to improve working conditions. The management tried to put Amy in a quality control job — “because I was white” — but she wanted to see what the cutting floor was like. She lobbied successfully for a knife job. It gave her carpal tunnel, and tendonitis.

Eventually, Amy moved to New York, getting her BA in anthropology from Hunter College just as the recession hit. Looking at the economy, she made the same decision as so many others: she stayed in school, thinking she’d enjoy being a librarian. But it turned out the librarian market was squeezed too. She got interested in archives because frankly, there were more jobs. So now Amy goes to school, works part time, and plays classical violin gigs. She shows up to meetings, now and again, carrying her instrument. She worries, she told me, because she doesn’t have health insurance and lives with roommates, and she’s now 35.

Amy heard Jez speak that day at the meeting and found him in the crowd, offering to help. Her practical soul had the potential to serve as a great complement to his grand ideas. Soon she too was carting signs on the subway back home to Queens. But it was rapidly apparent that the job of collecting these things, let alone organizing and cataloguing them, was going to take more than one person. And Amy and Jez were sometimes met with resistance; people did not understand why they wanted signs, or why it was important to preserve anything at all.

People throughout the movement were forming what they called “working groups,” which were, more or less, exactly what they sounded like: groups of people interested in doing the same kind of work, organized along non-hierarchical lines. Amy and Jez decided to form one for the Archives.

***

I’d been working part-time at NYU’s Tamiment Library for only a few days when my boss there mentioned she’d heard there was an effort afoot to collect Occupy Wall Street signs and pamphlets. I Googled “occupy wall street archives” and didn’t find much. But one listing for the working group’s first meeting finally popped up. It was on the blog at Amy’s school.

It was only when I reached the park that I realized that the listing hadn’t said where I should go. The library seemed like a natural bet. I began talking with a young librarian, a woman whose name I never quite caught. She didn’t know anything about the archives effort, but started asking me questions about it. Never having had much of a talent for thinking on my feet, I said something about hearing it was a collaboration with NYU.

The librarian’s eyes changed. “Oh yeah,” she said. “I have heard about that. And I have a problem with it, as a librarian. I want to know why we are giving our stuff to capitalist, money-grubbing NYU.”

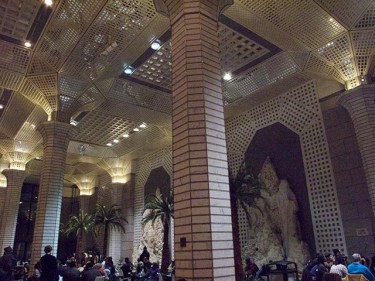

Soon after, Jez and Amy arrived and introductions made. We took off for the atrium at 60 Wall Street. The atrium (like Zuccotti Park itself) is privately owned public space. It makes for a pretty decent de-facto conference center. There are twenty-odd white plastic tables, and a large complement of matching chairs. The overall aesthetic is best described as early-90s-suburban-mall, complete with palm trees, an ersatz waterfall, and recessed mirror-tiles. Reporters have derived several “isn’t this ironic” stories from the fact that the skyscraper rising above the atrium houses the New York headquarters of Deutsche Bank, but every person down there I mentioned this fact to shrugged. There is wi-fi and a (rather filthy) bathroom. By the archivists’ second or third meeting, the atrium was so packed with different working groups that the first order of business was always securing chairs, which one usually had to spend the rest of the night defending.

Since that first meeting, the Occupy Wall Street archivists have met every week in the atrium, on Sundays at 6. Amy and Jez usually “facilitate” the discussion, and as such remain de facto leaders. There were anywhere from four to twenty people in attendance. The group split responsibilities into three streams, the first tasked with the archiving and storage of physical materials, like signs and pamphlets and what archivists call ephemera. A second task was the collection of oral histories. And the third was the archiving and collection of digital materials. The last was immediately taken over by a bunch of students from the Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program (MIAP) at the Tisch School for the Arts, who arrive en masse to one meeting. There were few agendas and fewer minutes kept, but things trundled along, slowly.

The tone of the meetings was generally professional, particularly when contrasted to the more emotionally charged discussions that were often happening nearby. One night, for example, we were quite near a frustrated argument in some kind of technology group about whether the movement should have a website at all.

Some group members were, like the MIAP students, either current or aspiring professional archivists. But more than a few weren’t. Some just liked making media and wanted to help. Some were academics. Some were just hanging out around the park. One night, at a meeting, a SUNY Old Westbury professor named Samara Smith, who is a sound documentarian by trade and has been especially active with the planning of oral histories, pointed out that this might actually be a boon. Involving non-experts, she said, would make the whole project more democratic and inclusive.

***

James Molenda, 32, is one of the few Archives group members who actually slept in the park on a regular basis. Every time I saw him, during the occupation of the park, he was wearing the same grey wool sweater, a piece of duct tape stuck to his chest. The tape marked him as a member of the Sanitation working group, whose job was trying to keep the park at least minimally clean. James is tall and has sandy-brown hair that he sometimes pulls off his face with a bandanna. He’s originally from Indianapolis, got a degree in literary and cultural studies from William and Mary, and he now lives in Brooklyn. James is neither a librarian nor an academic. But you could probably call him a professional archivist, in a sense: he is the managing editor of FOUND Magazine, which publishes found notes and ephemera and is edited by Davy Rothbart and Jason Bitner of NPR.

I asked James several times how he identifies politically — and never quite got a straight answer. The first time I met him I asked why he stayed in the park, and he said: “There’s just so much to do here.” Later on he tells me that he doesn’t think of himself as much of a protester, though, like everyone else he knew, he’d been “having really long arguments, and coming to different conclusions about economic policy, and politics, whatever, the types of things people in New York Cities in their twenties, when they’re not fucking partying, rail on about.” And the OWS movement just seemed different to him somehow. “It wasn’t just a march.”

James is, admirably, great at getting stuff done. At the first meeting it was already clear he’d be impatient with things like mission statements, and committee work. But he was full of strategies on how to collect the “sheer bulk” of materials in the park. He spoke of collaborating with Sanitation to get them to pick up signs, but that never quite came through; it’s hard to get them to understand why people might want to keep this “garbage.” Many in the Archives group itself seem to feel the same; most members are more interesting in oral histories and digital archiving. So for the most part, it’s James, Amy, and Jez who collect the signs, picking them up from their owners in the park or rescuing them from abandonment on the sidewalk.

They would then take the signs to the storage space the movement has set up in a storefront at the United Federation of Teachers’ building, popularly known as SIS (Supply, Inventory, and Storage). Archives had managed to secure a small corner for its purposes. The first time I visit the space seems huge and empty. But after a few weeks, the Archives area had been walled-in by boxes containing a donation of what James told me was $86,000 worth of comforters. That seemed like too much money until I saw them for myself, stacked to the at-least-14-foot ceiling.

One night it’s determined the boxes must be moved down the long corridor that snakes through the space. Someone stood, or rather balanced, atop the boxes, which were soft and pliable but heavy, and threw them down. James developed a toss-slide technique that I can only say closely resembles bowling. It inspired laughing and clapping all around. Which I mention only because it was one of those moments of unrestrained joy that might tell you why, despite the police hassles and the tedium of committee work, everyone stuck around.

***

One night in late October, after he’d finished his sanitation shift, James headed over to the cardboard recycling hub in the park, where he’d had luck finding good signs in the past. Seeing a set of ten or so that appeared bound together, he started to pull them out of the bin. Suddenly, he felt someone hip-check him and arms circling around to wrench the signs away. “That was the first time anyone at Zuccotti Park had really been aggressive about anything other than, I don’t know, hating Michael Bloomberg or being disgruntled that the Kitchen wasn’t serving food at 3:30am,” he later told me. The man was tall and lanky and had glasses and dark hair. He was perhaps in his late forties.

James tried to reassure this curious assailant that it was all right. He merely intended to save the signs for the Archives, he explained.

At this the man, whose name turned out to be Tommy Fox, replied: “No, it’s fine, I’m collecting archives.”

And then he left, taking his signs with him.

Amy and Jez ran into Tommy Fox too, some time later. Jez spoke to him, and asked if collaboration was possible. Tommy Fox refused. His stated grounds were that the signs were too important for history to give away. A rumor went around that he was working with the Smithsonian. Tommy Fox became an agenda item at the next meeting of the Archives working group: “The Rogue Archivist.”

I tried, for the purposes of this article and frankly to satisfy my own curiosity, to find Tommy Fox. But for a long time people thought his name was Tommy Knox, and only recently did I learn otherwise, so my efforts were stymied. Other journalists have run into him though — he is one of the drummers, 54, and this purports to be a picture of him, from the back. I called the Smithsonian, and they checked with their curators, who said the name didn’t ring a bell, and that they do not generally “outsource” their collecting. Perhaps Fox merely meant to donate the signs to the Smithsonian, and others misunderstood him. Perhaps it’s all just a rumor. But I have a feeling he isn’t, er, a card-carrying archivist.

The Smithsonian has, however, definitely been down there collecting signs themselves. So has the New-York Historical Society. George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has started up a collection too, though they told The Economist they’re mostly interested in digital materials, as is the Internet Archive. Of all of these bodies, the only one who reached out, directly, to the physical collection branch of the Archives working group is Tamiment. (The MIAP students are coordinating with some of these other institutions on digital issues.)

The entire idea of institutional collaboration is a fraught one. On the one hand, it could open up a world of resources and money. On the other, the longer the group remains independent, the more control it can continue to have over the shape of the collection, and most importantly, future access to the materials. This is a movement that has been heavily informed by the free-culture, open-source philosophy, and the archivists possibly even more so than your average protester. (At one point, while inquiring about Creative Commons licenses, Amy ended up being put in touch with Lawrence Lessig directly.)

When you’re with this group, you hear the word “transparency” a lot, and they really mean it. Example: I started recording the meetings soon after I started attending, offering to donate my recordings to the archive itself. The first meeting I recorded ended up being a large one, and the need for some kind of speaking stick arose. After I jokingly gestured to my recorder, the group ended up using it, passing it around and speaking directly into the microphone.

The ideal of independence, though, has been a difficult sell — as has the idea of the Archive itself.

***

The first real hint that the Archives group’s work might not be viewed as crucial to “the movement” came in early November. There is a long and, frankly, boring procedural story lurking in the background here, but suffice to say for present purposes that the movement itself had become frustrated with its primary governing structure, the General Assembly. A proposal to form a second governing body called the Spokescouncil was passed. It’s a representative body, and the representatives are chosen from certain working groups deemed “operational.”

But Archives, for whatever reason, did not get the consensus it needed to be so deemed. (“Operational”-ism, as it turns out, is a highly subjective property.) Several groups, including Sanitation and the Library, voted against it. James was the only Archives member there, and he wrote to me in email afterwards that he “had people talking to me like my parents had just died in a car accident… It’s just, ugh, feel like we just got voted off the island.”

The very next night, November 10th, the Archives budget was up for consideration by the General Assembly. The request, which had been discussed and workshopped extensively by the working group beforehand, was for $3,940. Most of those funds were to be devoted to a new, secure storage space. SIS was difficult for members to get into, and there were concerns about climate control to ward off possible mold problems. A large amount of the collection had spent some portion of its life out in the rain.

Amy and Jez got up to present the proposal. “Hi,” Jez yelled, holding a sign with a green lizard on it high above his head. He’d selected it because he wanted to give an impression of what the collection contained. “So we’re from Archives.” Jez told the crowd that the Archives to date had collected 300 signs, showing the diversity of perspectives in the movement. Amy read out the budget, and broke it down for the crowd.

The second the facilitators opened the floor for questions, it was clear that Archives had skeptics. People wanted to know if they had solicited donations, if they’d collaborated with the Internet Archive, if they knew about Tamiment, were Archives coordinating with other institutions to ensure that no duplicative work was being done, and on and on. By the time the facilitators called for the vote the crowd was uneasy. I was so stunned by this turn that James, standing nearby, had to kick me to remind me to raise my hands in the wiggling fingers that indicated an “aye” vote. The budget did not pass, and both Amy and Jez walked away looking ill, extinguished. We ended up drinking away the rest of our evening.

The defeat was made especially bitter by this: right before the Archives budget, the GA considered an emergency request for $29,000 to send twenty OWS protesters to Egypt to monitor the elections. Within three days OWS received a letter purporting to be from some deeply puzzled Egyptians. “Truth be told, the news rather shocked us; we spent the better part of the day simply trying to figure out who could have asked for such assistance on our behalf.” There was talk of overturning the GA’s decision, but ultimately the trip was postponed due to conditions on the ground in Egypt. It’s not clear what the current status of the trip is.

***

When the eviction happened five days later, James stayed until the bitter end, hanging out with a crew of holdouts gathered around the kitchen. He manages somehow to evade arrest.

Amy left the park as the raid was beginning. Later she said she wished she’d thought to take stuff with her, but she didn’t. She just left. The Archives group later tried to recover materials from the warehouse where the NYPD dumped what it had cleared from the park, but it had little success.

Jez was arrested at around three a.m., during the chaos of the post-eviction marches. He was charged with misdemeanor obstruction of governmental authority, and felony assault of a police officer. Because the case is pending, he can’t talk about what exactly happened. It is frankly difficult to imagine him assaulting anyone.

On the Day of Action on the 17th, Amy went on the march and crossed the Brooklyn Bridge with the other protesters. She asked some people for their signs. But they are hard to convince, because, they said, “History is now!” Her instinct for preservation was, they thought, premature.

***

Only four archivists showed up to the first Sunday meeting after the eviction. Jez, to whom no one has spoken since the raid, is reportedly out of town. Truth be told, things had been fraying between him and Amy for some time. Amy often frowned while he was speaking at meetings; Jez would talk to her without making eye contact. Jez was mostly interested, it seemed, in collecting the posters and bringing them around to galleries. He’d mention these plans at meetings, although it was never clear when and where he was taking things. His patience for the day-to-day administrative work of running the archive seemed to be running low. I wondered if he’d ever show up to meetings again.

James and Amy were there that first week after the raid, though. So was Shazz (given name: David McNerney), a quixotic figure who joined the Archives group just before the raid. He came in from somewhere out of town (I never quite get a handle on where), and quickly became involved in a number of different working groups. He offered to find the group a donated space, and keeps excitedly speaking of a basement in Harlem he’s found.

The group began discussing how to motivate other protesters to collect things, “people who aren’t insane pack rats,” as Shazz put it. A protester with a reddish beard, someone who had nothing to do with archives, came by to collect a piece of paper from a pad that hangs on the wall.

“Anything that’s written on these should be archived,” Amy deadpanned.

“Are you shitting me?”

“That’s what we do,” Amy continued over the rest of the group’s laughter. “That’s what we do.”

“I disagree heavily with that,” said the interloper, friendly but cautious. “And you know what? If you guys start picking around, like random shit that I leave around… you guys are just creepy.”

“Do you trim your beard over the sink over here, in the bathroom?” Shazz asked. “And what do you do with those clippings?”

“Oh my god,” the interloper said, finally getting the joke. “So now, you’ve got me on your side.”

But he doesn’t quite sound like it.

***

For the next few weeks the Archives group seemed to flounder. James, ever the logistician, began making a catalogue of the current collection. But the promised space in Harlem didn’t materialize. One week no one shows up for the Sunday meeting. The oral history group managed to organize a training, which garnered rave reviews from all who attend, but only a few have been collected so far. Shazz reported to the group that Yoko Ono was donating a piece to the Occupennial, and that she’d specifically asked that the archives keep it, but even if that were true (I requested confirmation from Elliot Mintz, Ono’s publicist, but never heard back), there is no secure area to store such a valuable thing.

I recently asked Smith, the documentarian and oral historian from SUNY Old Westbury, what she thought of the group’s inner processes.

She paused a moment. “I would definitely say that participatory-direct democracy is slow.”

We both laughed.

“But I am not frustrated by that,” she said. These conversations enable careful choices — and that’s important, she thinks.

***

It’s hard to say how many individual artifacts the archive currently holds. Today there are perhaps a couple hundred signs in the collection. There are also bags upon bags of pamphlets from every imaginable advocacy group. There are letters from the piles of mail the occupation received, though Archives does not have the complete set just yet.

The archival impulse is to collect first and ask questions later, and the pamphlets and signs collected represent a variety of viewpoints, some of more obvious value than others:

Due to popular demand, bank transfer day has been extended by me through the end of nov. Show your support. Either pitch a tent or transfer your $

Wes Taylor is a nonce.

When a piece of crap takes a crap, and that crap throws up, then the throw up takes a crap, That’s a 401K.

I want to burn Turkish flag.

Vote for Nobody. Nobody will keep campaign promises. Nobody will listen to your concerns. Nobody will help the poor. Nobody will bring the troops home. Nobody cares. Nobody tells the truth. If nobody is elected, things will be better for everyone.

Only about a hundred of the items are catalogued, so far. The group needs to find a space and time to process all the materials. They’ve recently been offered a shared space in Brooklyn Heights, which may mean that they can finally remove the materials from SIS, and from various people’s apartments. They’re continuing to talk to Tamiment about that being the eventual permanent home for the materials, but it’s hard to say what will happen. There is no legal entity at the heart of OWS that “owns” this collection. Whose signature might go on a donation agreement is not clear.

Though it will always be the Occupy Wall Street archive, it’s also still an open question whether these materials, taken together, are representative of the movement as a whole. So much of the collection was done on an ad hoc basis, and a great deal of material was lost in the raid.

But maybe that’s not the right question to be asking. One night in late October, as we were leaving the 60 Wall Street atrium to walk back to the General Assembly in the park, I fell in beside James. He asked me what else I was writing about Occupy Wall Street. I said I was only writing about the archives.

He looked surprised. “But I feel like this is such a small, bookish part of all of this. There are so many other parts to this thing.”

And I knew that. But it also felt like it might be the point.

Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her on Twitter.