The Google Goblins Give Firefox a Reprieve -- But What About the Open Web?

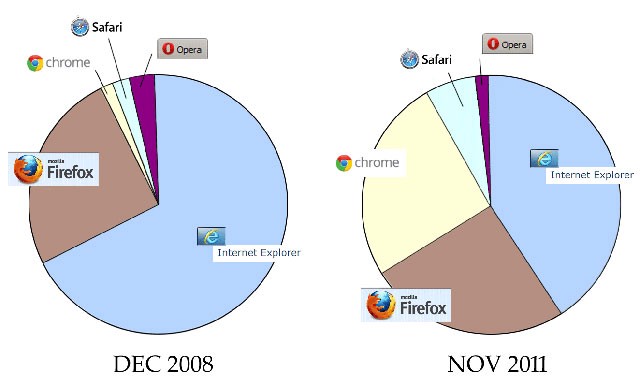

Data from StatCounter.

Did you know that most of Firefox’s budget comes from Google? That is because Google pays the Mozilla Corporation, the for-profit arm of the Mozilla Foundation, a share of ad revenue gained by displaying Google as the default Firefox search engine. By most, really, one means “almost all”: in 2010, 84% of Mozilla’s royalty revenue came from Google, and royalties counted for $121 million of the Foundation’s $123 million in income. Pretty good sugar.

The agreement expired in November. (It first expired in 2006, was renewed through 2008 and then again through 2011.) The rapid growth of Google’s Chrome browser threatened the survival of Firefox. There was no obvious need for Google to continue to subsidize a principal competitor. This caused much handwringing — until this afternoon, when Mozilla announced, at last, that it had signed a “new agreement” to keep Google as its default search partner for another three-year period.

Few of us have ever paid for a browser, so it’s hard to think of this in terms of ordinary business competition, but that is in fact what it is. And to the victor will belong the spoils of the enemy. With three years of deal in place, the prospects for the (sort-of) nonprofit Mozilla browser look better. And what happens beyond that?

You are also welcome to read this later with Instapaper.

In an ideal world — an ideal world which will apparently exist until at least 2015! — we’d be able to continue to search the Internet ad-free — or at least, browse ad-free. This is a public good that affects everyone; I, for one, would welcome a government initiative to produce an ad-free, not-for-profit search engine; an ad-free, not-for-profit digital library. We have the resources but not the political will to make things like this happen; understandably enough, since the political will is difficult to muster in an America where about half of our “representatives” represent not their constituents, but their corporate masters.

Nobody who uses the Internet will deny that web users owe a debt to the engineers of Google. At the same time, Google has grown dangerously big for its colossal britches. Right now, in addition to its search engine, Google owns YouTube, Chrome, Google Books, Blogger, Picasa, Feedburner and Gmail and God knows what else, that’s off the top of my head. Google bought at least 26 companies in 2011, across a broad spectrum of business activities. Google’s ambitions do not stop there; their biggest acquisition so far, at $12.5 billion, was this August’s purchase of Motorola Mobility; they’ll be making proprietary phones and tablets next (though it’s said this purchase was made in order to secure the zillions of patents owned by Motorola). There’s no end to their resources, and correspondingly no limit to their attempts to dominate of every aspect of our lives online — which, increasingly, means our lives, period. Do we really want a single profit-making entity in control of this much of the Internet?

Google recently paid for a study carried out by Accuvant which concluded that Chrome is the “safest” browser against malicious attacks. And doubts arose not only because of the sensitivity of the recent negotiations between Mozilla and Google; the study drew criticism for having perhaps been specially designed to favor Chrome at the expense of Firefox.

But here we are, with Mozilla’s main income stream extended again. It gives Mozilla three years to grow the foundation’s fund further and look at new options. Meanwhile, one thing Google can do, for better or for worse, is spend money and not much notice doing so.

* * *

A substantial number of the Internet honchos with whom I spoke during this period didn’t seem worried about the future of Firefox — partly because the mobile browser market is dominated by the open source WebKit rendering engine and its derivatives, which include Android as well as Safari and Chrome, and mobile is the future, everyone seems to think. Furthermore, Microsoft and its Bing search engine were surely poised to replace Google’s alliance with Mozilla. Certainly there have been tentative moves in that direction already. (In addition, the Mozilla Foundation has a good amount of cash on hand.)

But even Android is not so open source as we’ve been led to believe; Google seems to be trying to have it both ways, playing the part of public benefactor, enjoying the open source “we’re the good guys” PR while maintaining what amounts to very tight control over the software’s development (here’s a good chart illustrating how).

Open source doesn’t necessarily preclude corporate control. Nowadays most open source code is produced by professional software developers working for big companies. Times have changed since Linus Torvalds first set out to create an unpatented and unpatentable operating system; as of 2006, two percent of the current Linux kernel had been written by Torvalds himself.

Jimmy Wales called it. “I think Firefox still has a strong negotiating position,” Wales, founder of Wikipedia, wrote in an email. “I think Google won’t let them go. Bing is ready and raring to go, well funded, and the aggregate share of the browser market held by all versions of Firefox is still 25.3% according to Statcounter. Does Google really want Bing front and center for hundreds of millions of users?”

A good point, except that Bing sucks so hard it draws blood. You can’t sort standard search results by date in Bing. There is somewhat less SEO pollution than there is in Google search results but, big deal, when Google is apt to return ten or fifteen times the number of relevant results that Bing does, and date-filtered if you want. Bing’s news results are anemic compared to Google’s. There is no blog search function at all. And let’s not even get into Google Books, which, I mean, that alone. If I were Google, I can quite easily imagine not caring two pins about Bing, at least in is current state.

It’s hard to see how an alliance in 2015 between Bing and Firefox would benefit Mozilla much, or harm Google. If it is a revshare deal like the Google one, it’s beyond likely that Mozilla’s revenues will plummet anyway, because Firefox users will quickly learn to hop over to the Google website for their searches, leaving Bing without much rev to share.

* * *

So what, right? Why should we care about this? Well, we should care because these huge companies — Google, Amazon and to a lesser extent, Facebook — are increasingly in a position to wreck the Internets we’ve come to love and rely upon over the last 20 years. When the benefits that accrue to citizens come into conflict with the profit-making ambitions of the corpocracy, it has long been clear who will lose, absent an almighty fight. The unstable future of a dominant nonprofit, open-source browser is cause for concern to anyone interested in the preservation of the open web.

What is meant, exactly, by this phrase, “the open web”? Kip Hampton, author and Perl wizard, says it means a combination of three factors:

1) Free and open source servers and publishing tools, which means you don’t need money to publish web pages, provided you have Internet access;

2) Transport protocols and other technical specifications that are not encumbered by patent or copyright claims (so that tools like browsers, servers, etc. can be freely implemented by anyone who is willing to put in the time to develop them); and

3) The general assurance that connecting to the Web means the ability to connect to all of it, without some intervening public or private authority filtering/blocking/throttling access to sites and other resources they don’t like.

There are a lot of potential choke points there that could be exploited by a monopolistic corporation — one, say, in absolute control of browsers and search at the same time. In the U.S., attempts to kill the open web are being made not by political forces, but by forces intent on making you pay (or does that maybe come to the same thing?). Let’s follow this out.

As Chrome gains the monopoly it seeks in the browser market — Chrome 15 just now became more popular than Internet Explorer 8 and Firefox, by some counts — that will create a very different set of problems from those posed by the earlier dominance of Microsoft’s IE browser. Microsoft, unlike Google, never managed to stake out a controlling position in the search business; the nature of search is such that it automatically affects both online retail and social networks to a significant degree.

Even today, business software is Microsoft’s bread and butter. Once Microsoft has sold you a copy of Windows or Office, that’s it, you don’t pay for it again until a new and useless set of upgrades comes along to be shoved down your throat. That is a very old-school manner of going about things that is liable to break down in the nearish future.

Because, in stark contrast, Google’s business is the flow of information. When you watch a video on YouTube, Google makes money; on every Google search you perform, Google makes money; when you check your Gmail, even, Google makes a tiny bit of money, because there is an ad on there (for example, the one I just saw for the DeVry for-profit “university,” which when you think about it, this whole thing is liable to make you pretty ill, one way and another, because you can’t help but think, look, wouldn’t it be better to pay something for these services, so maybe I wouldn’t be a party to all these underprivileged kids getting tricked into a lifetime of hock to a load of tax-avoiding for-profit jerk-offs?).

Anyway, the point here is that Google’s true business is not search, but advertising. More than 96 percent of Google’s $29 billion in revenue last year came directly from advertising. Google makes more from advertising than the whole country’s newspapers combined. But Google News isn’t producing a newspaper; it’s aggregating and distributing and sometimes even propagating the results of work done by now-starving newspapers.

So. Ugh! The real question is, once they’ve got us by the cojones, what happens next?

Google does not have to stay free forever. (Free of charge, I mean. They are plenty free in the sense of unconstrained, what with their roaring Niagara of lucre and their eight corporate jets.) There is nothing to stop Google charging us for their services tomorrow.

We’ve never had to pay for a search engine yet, but if Chrome should take over completely, or nearly so, from Firefox and IE, that is a not-at-all-unlikely scenario. Google could absolutely forbid its search engine to any browser other than Chrome, for example, and if Google search maintains its absolute dominance — likely, for the foreseeable future, given that not even Microsoft with all its bazillions has succeeded in launching a viable competitor — no browser that literally does not include Google search would be usable, really. At that point Google could institute a paywall, of some sort. I think, really, would institute a paywall.

But that’s not even the worst thing that could happen if Chrome were to achieve more than, say, an 80% market share. The worst thing is that then Google would be in a position to determine even more basic aspects of our ability to communicate on the web. (Theoretically, they threaten the open web even now, for they may conceivably be able to control who is able to see what websites just by shutting undesirables out of the Google search engine — or by promoting desirables to the top of results.)

Google seeks to host every document you write and every email you send, they want to show you every book, host your blog, host your photos, answer all your questions. Google offers, apparently, a competitor to Groupon. What the heck. I do not want the entire Earth to be blanketed in products made by Google, Apple, Amazon or any other soi-disant “builder” of “cool applications.”

But that’s what nearly of all today’s other capitalists have done: exploit every advantage until it screams in pain, at all times. Not to have a solid business offering a good product at a fair price, not to be one among many, but to Take All and be the Winner.

Google search is the one indispensable Google product. There are tolerable alternatives to Gmail right now, and to YouTube, and there are more-than-tolerable alternatives to all the rest of Google’s offerings so far. That means that if they get too greedy, we can vote with our mice; we’re the assets, clicking and clicking, and we can take our clicks elsewhere.

But what happens when there’s nowhere left to click to? Ruin is what happens then. Things get more and more expensive and difficult, and quality crashes and burns.

Exhibit A: Facebook

The best days of Facebook are far behind it. When was Facebook’s best moment? I asked these all these youngs. One recalled, “Let me see, I was a freshman, in 2006” (causing me to inhale gin and tonic right up into my brains, practically). In 2006, because that was when you first got to put pictures up, she explained; before that, it had been just the one profile picture that you could have. “Before chat,” said another.

For me, the charm of Facebook ended when my list of favorite books disappeared. The astonishing thing about the original lists of favorite things on Facebook was that you could instantly see anyone else in the Facebook land who was interested in anything on your own list. It was so surprising to discover this. Really popular things would show tens of thousands of devotees, but so many times, there would be just ten, or 100, or even two. Once in a while it would be a friend, or a friend of a friend, who shared a hitherto unknown and unsuspected taste for The Lost Scrapbook or the solo works of Yukihiro Takahashi. A magical thing. I friended a couple of complete strangers just because they were fellow Thurber freaks. These connections were random, unmonetized, unmediated. We can still do this on the Internet now — on Twitter, say, the new home of random and improbable connections — but not on Facebook. Not any more.

One day, my list went up in smoke. Poof! Perhaps there had been some warning, but I missed it, I visited but rarely. I had no backup list; it emerged that you would have to start over. Then, I was shocked to find, the new system accepted only recommendations linking to these Fan Pages that are anything but places for serendipitous connections: they’re just marketing. Even when you’ve already met someone over a book you both like, there is a piece of the transaction to be got, if only in the form of a couple of Sponsored Posts on the right edge of the screen. Every day Facebook grows more suffocated with advertising; each interaction, each game, each moment you spend on Facebook is more and more clearly becoming like an ad-stuffed magazine, only you and your friends have to write all the editorial yourselves.

Facebook continues to “own” every bit of personal, private information we’ve ever put on there. As a nineteen-year-old Harvard student, Mark Zuckerberg offered other people’s private information (gathered from Facebook’s earliest incarnation) to a friend. I have all these thousands of emails, pictures, SMS, he bragged. “What? How’d you manage that one?” asked this name-redacted friend. Zuckerberg replied, “They trust me — dumb f**ks.” The mystery is how anyone imagines Zuckerberg to have altered his original position by one iota. He told Jose Antonio Vargas in a New Yorker interview, “I think I’ve grown and learned a lot” since those instant messages.

His company’s behavior indicates otherwise. The number of privacy scandals there is really shocking.

There are growing indications that people are fed up with the once-loved Facebook. Nicholas Carlson at Business Insider noted that revenue numbers recently leaked to Gawker look “a little light.” Light, that is, given that Facebook looks to be coming in shy of the $4 billion in revenues it would take for them to “meet expectations” in advance of next year’s IPO. $100 billion is the valuation number that has been floated for a number of months but I don’t think they’re going to get anywhere near that, for two reasons. One is the diminishing attractiveness of the feature set, as indicated above. Gone are the days when you could randomly locate some guy in Montana who loves The Book of Tea.

The other is that the bloom is off the rose for the youngs, as well, but in a very different way. Facebook was a novelty for twenty-somethings back in 2004; younger kids who grew up with it and are entering their twenties now are experiencing a certain level of burnout. They had Facebook all the way through high school, they already have two thousand “friends” and have long since grown tired of spending hours on the thing every day. For them, Facebook is liable to go the way of Hanson or Tamagotchis. It’s not a new toy, but an old one.

But even if the IPO is postponed, or Facebook is forced to take the company public at a diminished valuation (like $80 billion or something!), there is no social network anywhere that is half as pleasurable or entertaining as Facebook once was, and Facebook itself has strangled the possibility of a new one developing, at least for now.

Exhibit B: Amazon

Amazon bought the first dominant rare book search engine, Bookfinder.com, in a pretty shifty-looking deal made in 1999, and then bought the next dominant rare book search engine, the Canadian Abebooks, in 2008. If you’re surprised that Amazon owns Abebooks.com, that is understandable, since the word “Amazon” appears zero times on the home page of Abebooks.com. Perhaps Amazon is not very keen that we should realize that it is getting increasingly difficult now to buy a book online, new, used or rare, where Amazon is not getting a piece of the transaction. You’ll be paying more, that’s almost for sure, if you choose Powells or Barnes and Noble, though there are still very good deals to be had at eBay’s Half.com.

Independent booksellers have been fighting tooth and claw since the late 1990s to avoid being swallowed up by corporations, but years of struggle have seen them reduced to sharecroppers. Fees for booksellers at Bookfinder were a flat $25 per month (except for really large inventories), with no commissions, but these days booksellers must pay Amazon through the nose, with a far larger monthly fee plus a hefty commission on each sale, plus they wind up eating quite a bit of shipping costs — that is, if they want the huge preponderance of online book buyers to see their inventory. And all this was deliberate. One saw it coming, even in 1996.

And this means that struggling independent booksellers have less money to spend on inventory and on restoring books, on printing newsletters and attending auctions. It means local used bookstores close. It means fewer experts know less about fewer books. It leaves us all very much poorer.

Kip Hampton articulated our current predicament very beautifully, I thought.

The concrete short-run benefit of saving $50 at the check-out overwhelms long-run concerns about what happens when the family-owned store down the street goes under […] you can gas on ’til you’re blue in the face about walled gardens, privacy issues, and dependence upon private unaccountable profiteers who can change the rules on a whim but those abstract arguments usually crumple when pitted against peoples’ short-term needs.

[T]elling people they should do without some short-term benefit in order to gain a more important long-term one is a tough sell. Really, this is the heart of the challenge we face. People will flip over cop cars to stop some governmental agency from restricting their freedom but those very same people will willingly *give* that same freedom away to some private entity provided that they also get some short-term visible benefit in the process.

And so today we have Amazon, the biggest-box store of all, only the box is super far away where you won’t see their slave-wage employees passing out in the heat.

They say it’s an urban myth about the frog in the pan of slowly-heating water. Which I was very relieved to hear, if only because I’ve always found it so horrifying that anyone would have tried boiling a frog to find out. But it’s a story that resonates all the same. Sometimes I feel like we’re all of us in that pan, with the water having heated up to just past the steaming-Jacuzzi level.

* * *

The progress through Congress of the Stop Online Piracy Act has caused a very large number of people to sit up and take a bit more notice than usual. (SOPA has been halted for the moment in Congress, but only until Wednesday — again since canceled — but at some point there will be an attempt to weasel it through, so a call to your representative is possibly in order.)

If SOPA fails, it will be a hope-giving sign that citizens are waking up to the many dangers threatening the open web. It seems unimaginable, but it is in fact altogether possible that we won’t get to keep this miraculous thing we’ve all built and are sharing every day.

Here is a really crazy idea. What if the global Occupy movement were to unite behind Mozilla, and other open web initiatives? For example, what if Mozilla’s $100+ million Google dollars each year were to be replaced by an annual subscription paid by the many friends of the anti-corporate-greed Occupy movement around the world? You’d need 10 million people paying $10 per year, or you could have a tiered system like they have in public radio.

That is kind of how open source started in the first place, in opposition to the corpocracy. Kip Hampton described it this way:

[W]e came of age in a time when fighting the corporate stranglehold on software generally was one of *the* defining issues for anyone using or writing Open Source tools. We didn’t just use (or write) OSS software because it was there, because it was popular, or because it it was free […] there was a general agreement that we were providing an alternative to for-profit software and anything that even *looked* like it might lead to corporate control/co-option was strictly anathema. More to the point, we could just assume that everyone we collaborated with was on the same philosophical page because no-one who didn’t already “get it” would even show up in the first place.

Its a different world now. People download Firefox because it’s a great browser; even the most business-y business behemoths mostly use OSS server software because that’s what everyone uses; proprietary scripting languages and development frameworks have largely gone the way of the dodo; yet we greybeards still act like everyone who shows up is naturally “on the team” and, thus, we don’t need to explain why OSS is important.

The Occupy movement was united on the Internet. Maybe it could establish a beachhead for the survival of the open web, too.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.