Some New Directions

by Thomas Beller

Lou Reed wore black. He moved slowly and a bit stiffly through the darkness that had descended on the Great Hall, a sheaf of paper in his hand. For the last thirty years he has looked like an ageless lizard but now I felt concern for him at the sight of his stiff gait. He entered the circle of light and put on reading glasses, gold rimmed.

Just a few minutes earlier the audience had been treated to several facts. One of them, shared by the Dean of Cooper Union, was that Abraham Lincoln had spoken in this very hall. I have been to a number of events at the Great Hall over the years and this fact has been reported on every occasion. The space — a scooped out amphitheater underground, slightly redolent of a bunker, with a domed ceiling and gothic arches — resonates with the evocation of Lincoln’s speech having been spoken into darkness over and over for decades, centuries. The other fact was that although the program listed him later in the evening, Lou Reed would now go first because of another commitment. Immediately I began to imagine what this commitment might be, if it was another public appearance, or a dinner with a friend, or some complicated mélange of professional and personal socializing, or if he was just tired and wanted to go home and watch TV. At any rate it was going to be an evening of circling around and engaging with the avant-garde, and Lou Reed was a fine ambassador for this world, whose literary iteration has always made me feel a bit uncomfortable, even reproached. I was one of the presenters that evening, so in this encounter I felt somewhat beyond reproach. I was eager to see how it would all look when freed from the defensive position.

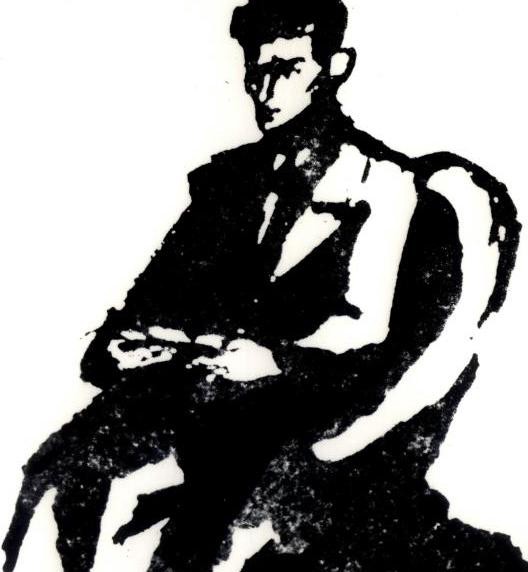

Reed began to read “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” by Delmore Schwartz. Behind him were three huge screens which were now filled with a photograph of Schwartz, dapper in a suit and tie, luscious full lips and no sign of the madness that was to undermine him. The mood of the moment was that of the early minutes of an art house film, black and white, scratchy and intense — an analog atmosphere. I half expected to see a credit for Janus Films or New Yorker Films appear followed by the somber opening shot of something from Goddard, De Sica, Jarmusch.

Maybe I felt this because “In Dreams Begins Responsibilities,” itself takes place in a movie theater. The narrator settles in to watch a film of his parents’ life before he was born. Scenes from a courtship, with commentary from its offspring.

Of all the material in the New Directions catalogue, whose 75 years we had gathered to celebrate, and which includes such familiar names as Ezra Pound, Borges, Henry Miller, William Carlos Williams, Roberto Bolano, and Tomas Tranströmer (who just won the Nobel prize), this book by Delmore Schwartz, and in particular this story, is the one with which I am most familiar.

Reed read in his monochrome Long Island accent. The sound system was excellent. His tone was conversational, matter of fact, pitched just a little towards tension. We sat in the dark watching Reed in his pool of white light at the podium, hearing about a man sitting in the darkness watching bright images on the screen. The movie theater, and the movie, are set in New York City.

You are also welcome to read this later with Instapaper.

Somewhere along the line the American avant-garde in literature moved back into the America from which it traditionally fled; nestling in academia, or just in cities with low rent. Dalkey Archive Press, located in Champaign, Illinois, is just the most conspicuous example. Large parts of its catalog are crusty New Yorkers like David Markson, who lived in a studio in the West Village, and Gilbert Sorrentino, who did his time in California but came home to Sheepshead Bay to die, and Carole Maso, now a country matron but for a long time a bohemian who made rent by cleaning Manhattan office buildings at night. Listening to Reed’s voice, remembering the voice of Irving Howe, and imagining the voice of Delmore Schwartz, was an affirmation that the avant-garde had once had a distinctly New York address.

Reed’s hands trembled a little as he turned the pages. His rendition may have deprived the story of some its humor but he brought other things to it, most notably a sense of place. That accent! On the early Velvet Underground records it is not so noticeable, in the same way that when I was a kid and listened the Beatles I assumed they were American; when I first heard them speaking it was a shock. In Reed’s later, solo work, his singing becomes a kind of declaiming and he comes out of the vocal closet as a New Yorker, specifically a guy from the boroughs — even if he is from Long Island — someone familiar with “the Dirty Blvd.”

I started thinking of how many of Andy Warhol’s Factory gang were outer borough people — Reed; Mapplethorpe with his hard core Queens accent and Patti Smith with her New Jersey sound; Paul Morrissey, who made the movies, and Donald Lyons, who wrote about them and was Edie Sedgwick’s muse, from the Bronx and Queens respectively, as was Danny Fields, who managed the Velvet Underground and brought Sedgwick into Warhol’s circle.

Now the screen behind Reed featured the cover of the book itself, edited by James Atlas and with an introduction by Irving Howe. Reed’s voice was like a conduit to an earlier New York, a place of immigrant striving that was directly engaged with literature and politics in a way that feels abstract now, that incredible gang of Jewish Intellectuals; Schwartz, Irving Howe, Daniel Bell, Irving Kristol, Norman Podhoretz.

The payoff of “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” (spoiler alert) is when, at a key moment, the interior voice we have been listening to suddenly surfaces and he begins shouting at the screen. “Don’t do it!” he yells. “It’s not too late to change your minds!”

I thought Reed did this well but I also felt he had sold some humor or dynamic in it a bit short. But then the story continues to a place I had forgotten about — an usher grabs the narrator’s arm and throws him out of the theater, all the while delivering a lecture on the perils of acting crazy, how the narrator is too old to behave like this, doesn’t he know that? “Everything you do matters too much!” says the usher.

Reed made that usher come alive. He left the pool of light to applause. It was, by far, the lengthiest presentation of the night, appropriately. Reed was Schwartz’s student at Syracuse, and is writing an introduction to a new edition of the book.

Nicole Krauss, in dangling gold earrings, came next, a solemn presence. She talked about her special bookshelf where she keeps her most extra favorite books — only a slight paraphrase — and what a large number of them are from New Directions. She read from the work of Yoel Hoffmann. He was an author, I decided snappishly, whose obscurity seemed justified.

There was one vivid image — a carp that had been caught in the sea is brought home and put in a bathtub. It swims back and forth for two days, up and down, and then the Aunt in the story, its main character, declares, “That fish thinks just like us,” and insists it be brought back to the ocean and set free. Hoffmann was one of several authors I was introduced to that night who possessed the distinction of not eliciting my interest. (Though having now slandered this guy, and by extension Krauss, I will now probably feel guilty and therefore develop an attachment to him; I will have to read him to justify or overturn this blithe assessment.)

Paul Auster appeared in triptych on the giant screen, sitting in his study on a grey-green leather couch, hair combed back neatly over his head. Another New Jersey kid, you can hear it at the edges of his voice, he began with an encomium to New Directions in general and then began talking about George Oppen, a poet. He read a striking piece of prose about the predicament of men who wished to avoid the German draft during World War II and who “dug a hole.” In this hole they lived for up to two or three years. Winter was a problem, not for the cold but because anyone who delivered food to the hole in the snow would leave tracks. The only safe time to deliver food was during snowfall. One man knew of the locations of a couple of dozen such holes and kept these men alive. But he had his own problems, which the story — could it have been a poem that Auster read as prose? — goes on about in fascinating detail.

I had expected the flatness of the screen to make Auster’s appearance dull, but there was an entirely unexpected and exciting aspect to it — we sitting, like a special guest, with Auster in the confines of his study. His place of work, procrastination, sex, or sexual thoughts, a private, interior space which was filled with books and pictures and other personal ephemera. I could not make out the titles of the books but their shape, color and texture were interesting — quite a few old bound items were part of a set, a number of these sets of two or three or four. The collected works of someone; not knowing who was almost as interesting as knowing. Framed pictures hung on the wall and also sat on his desk, leaning against the back wall, in black frames. It was a veritable Elle Décor sort of moment, and I thought of all the exasperating moments in movies and fashion shoots when someone gets it into their head that books would be useful as a prop, and how shamefully fake these moments are; the apotheosis of this being, perhaps, the lobby of the Mercer Hotel with its huge bank of books that, upon being touched, reveal themselves to be made of styrofoam.

Auster, perhaps trained by his years of Francophillia, has very nice taste. Over his left shoulder was a photograph of an attractive, stylish woman who I assumed was his wife. Though it could also be his daughter, the one he wrote about saving when she fell down the staircase and he happened to be there to catch her.

Part of me felt like I was intruding, but then Auster made his name with the New York Trilogy, books about highly stylized voyeurs, and his high minded fans often get all Rear Window on him, most famously the tourist from Turkey whose peripatetic stalking of Park Slope in search of the author was documented in the New Yorker. I am sure he has had to deal with less charming instances of this impulse. The rap on Auster, in my opinion, is that his voice, on the page, sometimes veers into Rod Serling territory. Once you enter the Twilight Zone it is hard to leave. But I could have sat with him in his study for hours listening to him read and talk about George Oppen.

Francine Prose was the first reader to make us laugh — behind her the screen filled up with the book cover of Gustav Janouch’s Conversations with Kafka. A work of non-fiction, Janouch, an aspiring writer, had a connected father who arranged for him to take long walks with Kafka through Prague. Kafka did most of the talking. At the end of these evenings Janouch would rush home and write everything down. Prose shared the following anecdote from the book: The two men are walking at night when they see, off in the distance, a dog cross the street.

“What was that?” says Kafka.

“A dog,” says Janouch.

“It could be a dog, or it could be a sign,” Kafka says. “We Jews often make tragic mistakes.”

The book’s jacket was up on the screen, a painting of a young Kafka against a bright yellow background, his expression handsome, astute, avid, almost leering. I felt a materialistic, acquisitive response to a book based on the design alone. Going all the way back to the stark minimal design of Ezra Pound and Djuna Barnes, New Directions has always had a flair for design but it’s tended to be black and white.

Prose talked about how, in lieu of cash, she took a gift of books as payment for her intro to the Janouch book, and finally settled on Microtexts by Robert Walser, page after page of tiny scrawl and fascinating design. Walser, as literary as can be, was mimicking the impulse of every ambitious art director I have encountered at a magazine, namely to make the font so tiny that the words are like conceptual decorations to the page whose main purpose is to make the white space look dramatic. It was a gorgeous book. New Directions have clearly staked their future on the fetishized physical object, one whose tactile pleasure correlates with its literary pleasure.

It occurs to me now, writing about Prose, and knowing her prolific work as author and journalist and literary activist, that her name could be a stage name, like Robert Zimmerman changing his name to mimic Dylan Thomas, whose voice had kicked off the evening.

Rackstraw Downes came next. He announced he had been reading New Directions for forty years and read from Eliot Weinberger. Somehow, perhaps because I was mulling over the name Rackstraw Downes, I missed everything he said.

Carroll Baker came next. It was not a name I was familiar with. A lady of a certain age, she came to the podium with a bounce in her step, radiating sass and good humor. She had short blond hair and pink sweater and announced that she would be reading from Tennessee Williams’ Sweet Bird of Youth. A still from the film appeared behind her in triptych. It featured a young woman who resembled Carroll Baker, in a mode of astonishingly sultry suggestiveness, curled in the arms of a man.

It took a moment to grasp that we were now being presented with two versions of the same person. I looked back at Carroll Baker, hoping to God that I wouldn’t think “I can’t believe that is the same person.” I didn’t think it; just the opposite, it was very much the same person and she stood at the podium a bit mischievously, as though somehow aware of this trick and our anxiety at what judgments we might arrive at. It was interesting to subsequently discover that her first job in show business was as a magician’s assistant.

Baker launched into a scene. We were in the hands of a performer and I was impressed by the reading, the posture, the scene, and the fact that while reading she chewed gum.

Also, I was very impressed that she wore no make-up, at least none that I could detect. The image behind her was replaced with the cover of the book, but that black and white still remained — a retinal burn that lasted all the way until she laughingly strode back to her seat to the sound of applause.

The poet Anne Carson’s presentation was listed on the program as including dancers and a saxophonist. The dancers were on film; they moved around a large spooky space followed by a kind of Zamboni with a spotlight gliding after them. The saxophonist was real, and stood behind her on stage, breathing sounds of accompaniment that were at times musical and at other times a sort of sound effect. She read from a book of poems about her brother, written after his death. The book, Nox, is based on a poem of Catallus, “Poem 101.” One word of the Catallus poem surfaces in each of her poems. She read the Catallus poem in Latin to start. Before the dancers appeared, a black and white still of a young boy popped up on the screens, her brother, “looking heroic in flippers.” She said. The picture itself only gave us a young boy, maybe thirteen, maybe ten, and the feeling of time lost, but beyond that it drove home that we were now going to be presented with an artful and intense processing of grief. I was riveted throughout, even in the really arty bits when the sax made funny noises, thinking that it was so great to see this in New York, in downtown Manhattan, in the Great Hall, which validated it somehow, as though here in New York you can do this, it is what people come here to do, even if they then disperse to university towns. Here, in this bunker, is where the oxygen is. I don’t know what Abraham Lincoln would have made of it all, the saxophone, the dancing singers, the slender woman at the podium. He may have been a big fan of Catallus. He may have understood the poem she read in Latin and not had to wait until the end when she read it again in English, revealing it to be about the loss of a brother. Perhaps he would have felt comfortable with its intense sense of loss and grief.

I made a mental note to read Catallus.

Fredric Tuten came next, and read from Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood, praising it even while saying it was at times a very difficult book to read, which I was heartened to hear, as I have never gotten very far in it. He then joked that he was tempted to read all of it. He laughed heartily at this suggestion. In me it instilled a moment of fear. Not that I thought he would do it, though you never know.

He told us how, after she moved back from Paris, Barnes lived in a tiny rent controlled apartment on Patchin Place, just behind the church at Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Avenue, until she died. Tuten told us her neighbor, E.E. Cummings, used to drop in regularly to see if she was okay. What stayed with me most from Tuten’s appearance was how, when he characterized Nightwood as a book about love, I felt no spike of interest, but when he said that it was also a book about the intense feelings of love rejected, I was interested.

Next was a short clip from the movie The Driver’s Seat, based on a novel of the same name by Muriel Spark. A parenthetical at the start informed us that Muriel Spark hated the movie; I later found out Spark was never paid for the rights, though whether this informed her opinion of it is hard to say.

The clip was deeply strange and wonderful in a kitschy 1974 sort of way: Elizabeth Taylor appears on screen in close up, furious; she is buying a dress, not in a store but in a showroom. She moves among mannequins, her eyebrows splendidly dark and alive; she is talking about the importance of natural color, natural fabric. The saleswoman she speaks to is Italian. The whole scene feels dubbed. When it is revealed that the dress is stain resistant, Taylor throws a hissy fit, storms into a dressing room behind a curtain, and tears off the dress. A moment later a more senior figure emerges to placate the angry Taylor. A flustered little dynamic ensues. The younger saleswoman tries to explain. Then Taylor steps from behind the curtain and there is a shocking moment of confusion provoked by the flesh-colored bra she is wearing. In the end it turns out the same dress is made without the stain-resistant chemical. The scene ends there. The heads of the mannequins between which Taylor has been moving are wrapped in tin foil.

I was next. I talked about a remark by James Laughlin, the founder of New Directions, about how their publishing strategy is built around the notion that a book takes twenty years to find its audience. Of course this is an utterly outrageous statement, wonderfully contrary, and possibly true. It echoes the famously amusing statement by Zhou Enlai, when asked by Henry Kissinger about his thoughts on the French Revolution: “It’s too early to say.”

A less provocative version of Laughlin’s remark is that readers have strange and peculiar needs. Their wishes are often perverse. It’s more complicated than supply and demand alone. Books sit for years on our bookshelves, mute and ignored, and then one day they call out. Maybe you take them down. Or maybe you just glance at them. And there it may end. Such a process may have to occur several times over a period of years before the book is even opened. But one day you suddenly think you absolutely must read this book. You may feel this at the exact moment you are unable to get to that book, at which point you buy another copy of a book you have spent twenty years not reading. At which point the fever may pass again, never to return. Or you may actually read it at last.

The New Directions author I spoke about was Niccolo Tucci, whose collection of stories, “The Rain Came Last and Other Stories,” is a favorite of mine. Part of the charm of his stories is their capriciousness. By way of illustrating the strangeness of a reader’s needs and desires, neither of which this reader is in particular control of, I spoke of how a month or so earlier I was in the manuscripts and archives division of the New York Public Library, perusing the letters and manuscripts of Niccolo Tucci, shortly before leaving on a trip to Cambodia. I had been to Cambodia before; I was going on assignment for a magazine; I had a lot to prepare for in the two days before my flight. There was absolutely no reason in the world I should have been spending time perusing marginalia by Niccolo Tucci. But there I was.

Tucci’s stories are histrionic, droll, charming, seductive, chaste in their concern for family life yet somehow acknowledging the ever-present libidinal chaos that springs from it — his voice has a naughty, Italian, libertine lilt. His letters are more extreme versions of this. The self pity is less comic and more urgent. I found them shockingly hysterical, in both senses.

I began by reading a letter written to him by an editor at the New Yorker, Katharine White, dated September 5th, 1947. It begins:

“Dear Mr. Tucci,

“I am sorry that you are having such a hard time writing but perhaps it will reassure you to know that what is happening to you is happening to dozens of other writers, my husband among them. He had not been able to work all summer and indeed has written less than you have, I know, since the first of the year. The awful state of the world is what makes a thinking and imaginative person half sick all the time.”

Then I read the letter to which she was responding:

“Dear Mrs White,

I should have answered your very kind letter long ago, but I was always hoping to send you a few stories as the best substitute for an answer. I have them: they are summer stories, and in a few weeks they will no longer prove acceptable. And I also have every other reason in the world to try and sell them now; among others the fact that I have borrowed money from the magazine and cannot pay it back. Yet I would be so grateful to you or to anyone else if anyone could tell me what it means when a man my age, with the problems he has and the wonderful opportunities that are offered him by magazines like yours, cannot even overcome the reluctance to get a few things copied and sent away by mail. I am now finishing a reporter at large on Einstein whom I visited recently with Bimba and my mother-in-law (who is also on my shoulders now). Einstein said many things that were quote interesting, then he played the violin for Bimba, so these are all things I could quite easily write down and give to Mr Shorn [sic]. But it will take me another week to do it. It’s not the heat, and not the family. They are away, in an abandoned farmhouse of the Addams type, near Harpers Ferry in Millwood Virginia. I am here alone, surrounded by my manuscripts. No one disturbs me except the world at large and the impending war, and of course the futility of all appeals to reason. This goes for me too. I appeal to my reason and nothing happens. Really, I am almost ashamed to show my face at the New Yorker now. Well, probably today, after mailing this letter, something will happen and I’ll work.

“Remember me with friendship to Mr White, please.

(then in a fountain pen scrawl): “Yours with best regards Nika Tucci”

From there I launched into a few paragraphs of his story, “The Evolution of Knowledge.”

After that I stepped off but not before adding, “It’s very difficult, and rare, for a publisher to be interesting, even for a short time. And New Directions has been interesting for a long time.”

This was my nod to the fact that a publishing house, if it lasts long enough, is not a single entity but includes many hard to pin down issues of succession, education and, most ineffably, taste. The same taste that informs an editor as they read a manuscript comes into play when hiring people to surround and eventually succeed them. James Laughlin started New Directions, he published the iconic books on which its reputation rests, and somehow this sensibility was passed down from one person to another and ended up with Barbara Epler, who is now editor.

Helen DeWitt came next. Limpid blond bangs and blinking furiously like a subterranean creature forced into daylight. There was a lot of stammering, fumbling with the microphone, gasped phrases. “Standing up here is like being in Kafka’s The Trial!” she finally blurted out and, a moment later, “Oh, they’re clearing out.” Chunks of people were gathering their stuff and heading up the aisles. Something about her manner of incredulity and excitement gave every indication that we were about to be treated to a kind of high art version of Sally Field’s famous Oscar speech.

I don’t think that every writer needs to be a loquacious figure of ease who is never happier than when her voice is amplified to a room, but all this stammering and blushing seemed a bit much. Then I considered that DeWitt was not just promoting a New Directions author; she was herself a New Directions author, whose novel, Lightning Rods, has just been published. These publication readings are, in my own experience, occasions for a mini-nervous breakdowns. They are supposed to be a celebration of the book’s publication, but for the writer, especially once you are past your first one when you and the book are pure potential and all your friends are there, they are going away parties, a kind of a wake; I wore all white at the first reading at Barnes and Noble for my most recent book. It was the end of summer; I hadn’t thought about it too much. But in hindsight it corresponded to my feeling that the reading was a kind of Buddhist mourning ritual in which the body is burned so the soul can roam free.

DeWitt, after citing the number of rejections her manuscript endured before New Directions took it (19), did get around to reading and talking about a New Directions author, Ezra Pound. Pound, she said, had been domesticated and made into a harmless pet at the college she attended, Smith. This so aggrieved her that she dropped out to live a life of hardship and adventure and become the person she is. She hammered at Smith College for a while and then at all English departments before pausing to say, “I mean, yay, English!” It was impressive, the hate. Then she read from Ezra Pound’s Cantos.

Next came Siri Hustvedt, who appeared on the screen seated on the same couch as her husband, Paul Auster, but at the other end, so we had the satisfaction of further exploring the room and its decor. Behind her was that photograph of herself, I think, her arms wrapped around her torso. But after a minute the video malfunctioned.

Next up was Paul Beatty. A big guy, lean but with some heft, he approached the podium with a curious body language that reminded me of that slippery quality certain boxers have, a bob and weave. He read from Roberto Bolano’s “Distant Star.” But first he talked a bit about New Directions books, and how he had always tried to avoid them. “They’d say, ‘Oh, you’re from L.A., you have to read Nathanael West!’ And I’d be like, ‘No! I don’t want to! I always hear about him. But then I’d have the book, and read it, and I’d have to wrestle with it.”

Francisco Goldman read last. He spoke of how New Directions had been a boon to his early adventures in picking up girls when he lived in Boston, and how they were the first books he ever purchased. He read from the work of César Aira, a prolific Argentinian author whose method, Goldman told us, was to sit down and just start writing until the book was done. “Don’t try this at home,” Goldman said. “Unless you have this particular kind of genius.” Goldman read from a book called An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter.

The evening wrapped up with Alice Quinn, head of the Poetry Foundation of America, who presented Barbara Epler with a black and white photograph of James Laughlin. He is seen in silhouette, smoking a pipe, a bit mysterious, even a little bit Hitchcockian somehow. Quinn was for many years poetry editor at the New Yorker, and she published some of the poems that Laughlin had begun writing in his later years. She told of a visit to his Connecticut home where, for lunch, she received an immaculate grilled cheese sandwich and Oreo cookies for dessert. Though this was reported in all innocence I took from it the feeling that Laughlin was an old school WASP who did something adventurous and meaningful with his money.

But that is a kind of praise as Percocet — it kills feeling and clogs you. Beatty’s remarks were the most memorable for me, because they acknowledged what a pain in the ass literature can be. Speaking about New Directions Books, with feints and ducks, he spoke of books not as some wonderful palliative, not as this delightful thing that can move and uplift us, etc., etc., but as frightening, demanding, intimidating and essentially bullying presences. Things he would often prefer to avoid. It was a bit like the feeling Italo Calvino evokes at the start of If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler, when he talks about a writer going into a bookstore and being besieged by all the books he hasn’t read but means to, or hasn’t read but ought to, all of them reproaching him.

In Calvino’s warm, Italian voice it has a humorous quality, but Beattie seemed to say that these books — specifically these New Directions titles that people kept giving him — were a pain in the ass that took him out of his own groove. “It happened with Bolano,” he said. “Everyone was going on about The Savage Detectives. The last thing I wanted to do was to read anything by Roberto Bolano. But someone gave me Distant Star. And so I had to wrestle with it.”

The evening was filled with challenging moments, but the whole time, even in the moments of resistance or boredom, I was awake in some essential way, which is why I was so eager to write this down this account of it. I wanted to get these thoughts down on paper, so to speak, before they vanished like fireflies whose beauty was connected to a specific time and place.

Thomas Beller is a cofounder of Open City. He teaches writing at Tulane University, and his most recent books are The Sleep-Over Artist, a novel, and How To Be A Man: Scenes From a Protracted Boyhood, an essay collection.