Larry David's Rough Night Out With The Aging Literary Lion

by Evan Hughes

A column that resurrects the highbrow gossip of yore.

In the “Seinfeld” episode “The Jacket,” which aired in 1991, Elaine recruits Jerry and George to join her for a drink and dinner with her father, Alton Benes. He’s a cranky old writer, distinguished but well past his prime, and he’s impossible enough that Elaine says she needs a “buffer” to spend an evening with him. (This comment might mark the moment when we all started using the word “buffer” in this particular way. “Re-gifting,” “double-dipping,” “low-talker” — in the lingo of the educated urbanite, all roads lead to “Seinfeld.”) Elaine ends up being late, and Jerry and George face some unpleasant minutes with the embittered and intimidating old author.

Alton Benes: Which one’s supposed to be the funny guy?

George Costanza: [cheerfully pointing to Jerry] Ah! He’s the comedian!

Alton Benes: We had a funny guy with us in Korea. Tail gunner. They blew his brains out all over the Pacific.

The character of Elaine Benes was loosely based on Monica Yates, who dated Larry David some years before he created “Seinfeld.” Monica Yates’s father is the novelist Richard Yates, the author of Revolutionary Road, a classic of the last American century. This scene was inspired by a real evening out with Richard Yates in the 1980s. Fun fact — but here things start to get less amusing.

Richard Yates, who died in 1992, became a literary giant at age 35 with the publication of his first novel, Revolutionary Road, in 1961. As Blake Bailey writes in his terrific biography A Tragic Honesty: The Life and Work of Richard Yates, my main source here, Yates was a worshipped figure in the ’60s on the faculty at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop — a towering example, a handsome man, and a generous teacher as long as you didn’t bully other students or think too highly of yourself. But over time he suffered repeated horrible bouts of depression and psychosis and became an often mean alcoholic.

One classroom show-off at Iowa who crossed him was his student David Milch, then 21, who went on to become one of the most powerful writer-producers in Hollywood (“Hill Street Blues,” “NYPD Blue,” “Deadwood”). Yates found him arrogant and obnoxious, an entitled Ivy Leaguer, and defended other students from Milch’s high-handed remarks. Yates’ ongoing complicated relationship with Milch grated on Yates over time, underscoring his long decline. In the ’70s, Milch was teaching at Yale and hinted that he might be able to arrange a job there for a struggling Yates. It was a galling reversal for Yates just to be hoping for Milch’s help — worse when the wanted job didn’t materialize. “Maybe I didn’t follow through,” Milch told Bailey.

Still later, Milch heard of Yates’ poor condition and offered him an easy job writing treatments and put him up in his guest house in Los Angeles. Yates couldn’t afford to refuse. It is a bitter irony that Revolutionary Road was made into a big-budget movie starring the Titanic duo of DiCaprio and Winslet only after Yates’ death; his books fell out of print in his lifetime and he really could have used that money. Yates hated the work he did for Milch and loathed being on the wrong end of this charitable gesture. He would lecture Milch on how badly the young man was selling out as a writer.

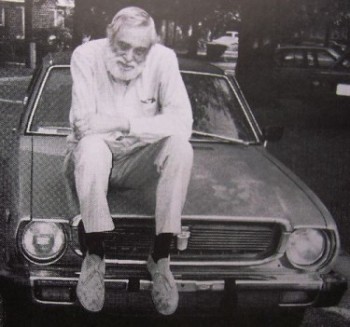

Monica felt a strong affinity with her father, unpleasant though he could be, and he made touching efforts to be a good father to her and her sisters. In periods when he kept it together, he and Monica would talk on the phone for hours. “He always got it, he always said the right thing,” Monica told Bailey. But he made things hard. When Yates was living in Boston, divorced and alone in the mid-’80s, Bailey writes, “former acquaintances would sometimes see a gaunt, stupefied, ragged old man staggering around the streets of Boston; an incredulous second look would confirm that the wretch was none other than Richard Yates. The usual impulse was to hurry away before one was recognized by this poor ghost, though of course there was no danger of that.” Monica said to Bailey, “You can’t be a doting daughter to a guy who falls apart like that. You have to be strong.”

Around this time, Monica asked Larry David, who had remained a friend since their breakup, if he would come out one night and meet her visiting father at the Algonquin Hotel in midtown. Despite his admiration for the writer, David wasn’t in the mood to be sociable (imagine that), but Monica pleaded; her father was sure to get drunk, and she “dreaded being alone with him,” Bailey writes. Monica was, in fact, late, and Larry David’s conversation with Yates did not go well. In an attempt at levity, David told a story about pretending to be suicidal to get out of serving in Vietnam. Yates remarked that he himself was a veteran of World War II. (If David figured that recreating this dialogue faithfully would not have been as funny as the exchange about the tail gunner, he was correct.)

Yates didn’t drink too heavily at the Algonquin, but he wheezed and muttered and seemed none too keen on David, who was thoroughly intimidated. As in the “Seinfeld” episode, when it came time to leave the hotel, David had a problem: now it was snowing outside and he was wearing a brand new suede jacket that was likely to be ruined by the snow. He considered turning it inside out but the jacket’s lining was garish (pink and white stripes on “Seinfeld”), and he didn’t want to be ridiculed by Richard Yates. Swallow the pride or swallow the expense? “I decided to eat the jacket,” David told Bailey. “It was never the same.”

An odd side note here: the actor who played Yates, Lawrence Tierney, was himself in the latter stages of a volatile life. While making his name playing tough guys from the ’40s (Born to Kill) to the ’90s (Reservoir Dogs), he also got into numerous drunken scrapes with the law, often involving violence. In 1975 he was questioned in connection with the apparent suicide of a woman he was visiting; he told police she “just went out the window.” (Tierney was also a regular, strangely, on “Hill Street Blues,” so David Milch knew both the troubled, alcoholic Yates and his troubled, alcoholic double.) During the “Seinfeld” shoot, Jerry Seinfeld discovered that Tierney had tucked a butcher knife from the set under his jacket, apparently planning to steal it. Jason Alexander, who played George, said in an interview, “Lawrence Tierney scared the living crap out of all of us.”

Richard Yates, alerted by Monica, ended up watching the “Seinfeld” episode with a few graduate students at the University of Alabama, where he had taken a job. He was 65 but seemed much older. He would be dead within two years. At the end of the show, Yates asked the others, “What’d you think?” One said, “Well, it was kind of funny, Dick.” “I’d like to kill that son of a bitch!” Yates roared and left the room. Monica felt the “Seinfeld” episode could have been so much worse. Larry David “could have focused on the physical infirmity, the frailness, the runny nose, the drinking,” she said. Instead Alton Benes was simply gruff and frightening. Monica told Bailey that she suspects her father was in fact more pleased than not by the episode; he just wanted to act indignant in front of his students. It had been thirty hard years since Yates had written what he considered his best book. At least Larry David still treated him as an imposing figure.

Previously: The Cordial Enmity Of Joan Didion And Pauline Kael

Evan Hughes’ book, Literary Brooklyn, a work of literary biography and urban history, has just been published. He’s on twitter.