Higgs and the Certainty of Physicists

by Ann Finkbeiner

The room is 100 percent physicists, 75 percent of them are likely to be under age forty, under 10 percent of them are likely to be female. They’re all unusually quiet, no scrooching, no whispers, motionless.

On two screens is the broadcast from CERN, the physics institute in Switzerland, of a scientific talk. Invisible in the air is the theory called the Standard Model, or at least one of its articles of faith, which you can read like it’s liturgy: the first fundamental particles in the universe had no mass; but as the universe cooled, it changed, and during this change a force called the Higgs field condensed into a quantum liquid, and the liquid dragged on the fundamental particles and gave them mass; and in the liquid, waves formed into a particle, and it was called the Higgs. Highly theological, but in the room on the screens is the first physical evidence that the Higgs is a fact. Sort of. Depending. The room has its own force field created by physicists, tense and ready to jump.

The broadcast has turned to questions and the young physicists in the room get tired of listening to people on another continent quibble and a pale, blonde physicist stands up and says, “So. Let’s summarize.”

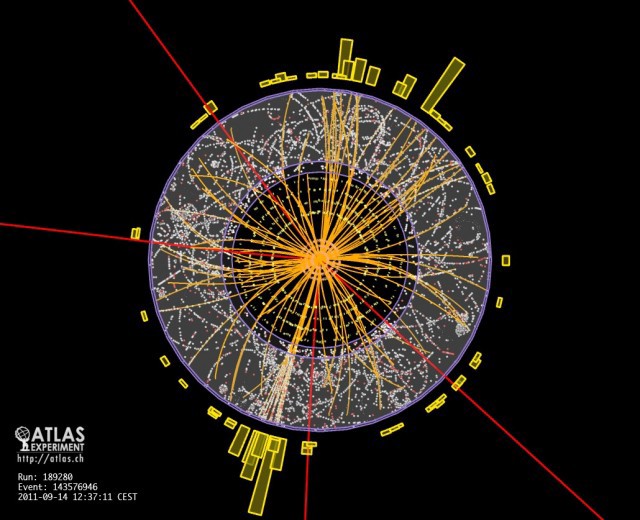

CERN has collided fundamental particles at enormous energies — hundreds of gigaelectron volts (GeV which the physicists pronounce Jev), over and over and over again, and each time has examined the energies of the particles that came out of the collisions. CERN has done this in two different experiments; the young blonde worked on one of them. He says the experiments together suggest that the Higgs’s energy is around 125 GeV. The physicists in the room are not that interested in the number, which is after all a matter of statistics — 125 GeV just had more hits, showed “an excess of events,” they say. They’re more interested in whether they believe it.

Physicists do the most lovely thing: they quantify conviction. They know what they believe to within four decimal places. They assign to their certainty a number called sigma: 2 sigma, you’re certain to one in a hundred; 3 sigma, to one in a thousand. Physicists remain restless up until 5 sigma, one in a million. In the room, the young blonde is waffling on the sigma; the physicists get pushy: “You gotta give us a number or we’re gonna shoot you.” You can’t really combine the experiments, says the blonde, but combine the experiments and the naive number, don’t take a picture of it, is 4.4 sigma.

Five chances in a million that’s it not true.

Quantification of conviction doesn’t always take the form of numbers. “I believe this one day in five,” physicists say, or “I believe this utterly and completely once a month.” Or: “I bet my house. I bet my grad student’s house. I bet your next paycheck. I bet my car. I bet my old car. I bet my dog but I don’t bet my child.” A Higgs of 125 GeV? You have a coin with a thousand sides, how many flips to come up with a fake Higgs? No, you have an unfair coin, how many flips would prove it’s unfair? The room of physicists, a little frustrated now,

turns to a physicist in late middle age who helped find the last hot particle, the top quark: Well? “I’d bet Mitt Romney $10,000 because he can afford to lose it.” C’mon, is this gonna be for real? The physicist pauses. “Sure.”

Well then. So what. The bible, the Standard Model, predicted the Higgs would be at a slightly lower energy, around 114 GeV. An extension of the bible called Supersymmetry — in which fundamental particles are made of strings coiled in 11 dimensions, and for which no evidence exists — predicted a Higgs that’s higher than 114 GeV. “Watch out,” says a physicist with dark curly hair, “tomorrow you’re going to see statements from supersymmetrists that 125 GeV confirms supersymmetry, and that’s absolutely not true.”

The bible’s opposite — cold hard fact — says that most of the universe is not stuff like us but something invisible called dark matter. Astronomers have been nagging physicists to find dark matter for years. Is the Higgs dark matter? To first even believe the Higgs is 125 GeV, says the blonde, will take more statistics and another year of data; but saying in seven-parameter space that it’s dark matter, that’ll take twenty years. “Twenty years?” says an aging astronomer. He stumps out of the room: “Oh Lord. I gotta keep going now.”

Ann Finkbeiner is a proprietor of The Last Word on Nothing.