Dreaming In Stereo: Why 3D Is Here To Stay

Dreaming In Stereo: Why 3D Is Here To Stay

by Maximus Clarke

1. “THE CASE IS CLOSED”

“For general use the single-tone [black-and-white] pictures will enormously prevail.” — Rupert Hughes, screenwriter, 1923

“[Sound film] is an exhausted toy, ready to be cast aside.” — David Belasco, playwright, 1930

“Television won’t last. It’s a flash in the pan.” — Mary Somerville, radio broadcaster, 1948

Roger Ebert knows that 3D movies just don’t work — and they never will. This past January, he wrote: “The notion that we are asked to pay a premium to witness an inferior and inherently brain-confusing image is outrageous. The case is closed.”

As Exhibit A in support of this verdict, Ebert furnished a letter from Walter Murch, the acclaimed editor of The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. Murch has a theory about how 3D films befuddle our eyes and brain, by confounding their natural convergence and focus reflexes: “They are doing something that 600 million years of evolution never prepared them for. This is a deep problem, which no amount of technical tweaking can fix.”

Ebert and Murch aren’t the only ones who find 3D movies unpleasant, unnatural, and generally unfit for human consumption. It’s estimated that 2% to 12% of the population is “stereo blind” to some degree: unable to see fully in three dimensions. This includes people with eye alignment disorders like amblyopia or strabismus (which can sometimes be corrected with therapy), people with certain optic nerve defects and, of course, those with only one functional eye.

And some people with fully working binocular vision nonetheless consider 3D films to be a headache-inducing waste of time and money. Two years after the phenomenal success of Avatar, with a host of rather more shoddily crafted stereoscopic spectacles having come and gone in the interim, there’s talk of a “3D backlash,” and studios are scaling down their plans for new 3D extravaganzas.

But I submit that Ebert is seriously mistaken. I’ve been intrigued by 3D since first picking up a View-Master as a child, and I’ve come to understand it much better in the course of producing my own stereo images over the past couple of years. What I’ve learned about the history of the medium, how it works, why it sometimes doesn’t work, and how it’s currently evolving has convinced me that it’s here to stay.

2. “WE CLASP AN OBJECT WITH OUR EYES”

Stereography — the art and science of creating artificial three-dimensional images — has its roots in the early 19th century. British scientist Charles Wheatstone crucially summarized the theory of stereo vision in a landmark 1838 paper presented to the Royal Society: “[T]he mind perceives an object of three dimensions by means of the two dissimilar pictures projected by it on the two retinæ.”

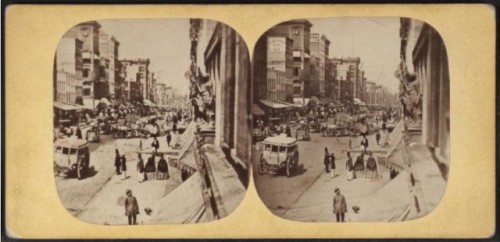

Meanwhile, across the Channel, Louis Daguerre was developing his eponymous photographic process. Very quickly, these two discoveries were combined to create stereoscopic photography. By the 1850s, David Brewster’s stereo viewing devices — recognizable ancestors of the View-Master — had infiltrated many homes. The public appetite for stereo images was fed by firms like the London Stereoscopic Company; in its first two years of business, it sold over half a million stereoview cards, each bearing a pair of photographs taken simultaneously from adjacent viewpoints.

In an 1859 essay in The Atlantic, Oliver Wendell Holmes described binocular vision in vivid metaphor:

“We see something with the second eye which we did not see with the first; in other words, the two eyes see different pictures of the same thing, for the obvious reason that they look from points two or three inches apart. By means of these two different views of an object, the mind, as it were, feels round it and gets an idea of its solidity. We clasp an object with our eyes, as with our arms, or with our hands, or with our thumb and finger, and then we know it to be something more than a surface.”

Holmes, a great stereoscopy enthusiast, developed his own immensely popular lightweight stereo viewer design. You can still buy or build a Holmes-style stereoscope, but with a little practice, you may be able to “freeview” side-by-side stereo images without any special gear, by letting your eyes drift until the pictures converge.

Old stereo view cards aren’t hard to find; they turn up frequently at flea markets and junk shops. Online, the New York Public Library has over 42,000 stereographs of American subjects in its collection. There are countless vintage 3D images floating around elsewhere on the Internet, including pictures of world landmarks, non-Western cultures and (inevitably) naked ladies.

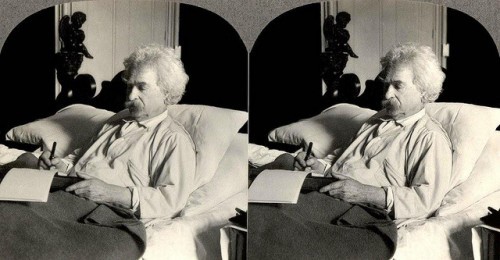

Victorian stereo views were the virtual reality of their era, but the faded images are something more than that now: for us, they’re a form of time travel. Viewing a 3D portrait of Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain or Charles Dickens taken over a century ago is like looking through a slightly dusty window into a living past.

3. BOOMS AND BUSTS

The first major wave of 3D films were produced almost 90 years ago. At least 13 films using the anaglyph process (which requires glasses with 2 different-colored lenses, usually red and blue) were released between 1922 and 1925.

This was an era of experimentation; filmmakers were also beginning to explore color and sound as ways to add new dimensions to the cinematic experience. But after the success of 1927’s The Jazz Singer, sound won out, and color and 3D were virtually abandoned.

By the early 1950s, color finally began to take hold in Hollywood. A newer 3D process, using different types of polarizing filters for the left and right eye, conveyed stereo images without anaglyph’s color distortions. Studio bosses, worried about their audiences being stolen away by television, saw 3D as a way to kick the theatrical experience up a notch, and perhaps keep more bodies in seats.

The dozens of new 3D features produced during the first half of the decade included popular titles like Bwana Devil, House of Wax and Kiss Me Kate. But the costs of shipping two prints for a 3D feature, instead of one for a conventional film, and the technical complexities of keeping two projectors in sync and in focus (or else inducing audience eyestrain), proved too burdensome for studios, distributors and theaters. The boom ended so abruptly that Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder, shot in 3D, had been downgraded to a 2D release by the time it hit screens in 1954.

The 3D medium lay mostly dormant until the 1970s, when it was used for a string of low-budget porn titles. (First link especially NSFW.) The major studios starting nosing around the technology again at the dawn of the 1980s, as they perceived a new threat emerging: the VCR. But moviegoers had mixed responses to high-profile releases like Jaws 3D and Friday the 13th Part 3. Once again, the expense and hassle of shooting, editing, printing and distributing three-dimensional films didn’t seem worth the modest box office boost. After 1986, no commercial 3D features were produced for the rest of the decade.

Over the course of the ’90s, 3D re-emerged within the growing network of large-format IMAX theaters affiliated with museums and theme parks. Unsurprisingly, most of the films produced were nature documentaries or family fare. Shooting and projecting on 70mm film made for better image quality than ever before, and a high degree of technical precision at every stage minimized viewer discomfort. The IMAX 3D trend grew slowly into the 2000s.

By 2007, another 3D wave seemed to be rising. Once again, Hollywood faced disruptive competition from emerging media: HDTV and file-sharing were leading many viewers to skip the theater experience altogether. The industry geared up to give stereography another try, with a new generation of technology that would further simplify and improve the process. Digital projection systems, already being rolled out in theaters, could be configured for perfectly synchronized, sharply focused 3D much more easily than the mechanical projectors of yore.

That year, CGI animators recreated the physical sets and puppets for Tim Burton’s stop-motion animation feature The Nightmare Before Christmas in order to generate a second point of view for each frame of the film. Harry Potter and friends rode their brooms into the third dimension for the first time. And the buzz began to grow about a potentially game-changing 3D epic from James Cameron.

Avatar unspooled in late 2009. Notwithstanding a cliché storyline, its impeccable stereo visuals were a mystical prog rock album cover come to life. By the time it broke all previous box office records, scarcely a month after its release, every producer in Tinseltown was scrambling for a 3D project.

4. MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE

The elaborate processes involved in creating and delivering 3D content are supposed to deliver a more naturalistic viewing experience. The obvious irony is that from start to finish, stereography involves far more artifice than 2D image-making: double camera systems, complex editing and special effects workflows, custom projection equipment and usually some variety of special glasses.

Several different types of 3D imaging technology are in wide use these days. The oldest, dating back to 1853, is anaglyph, characterized by those red and blue (or more rarely, blue and amber) glasses. In the anaglyph process, the picture intended for the left eye is rendered in a color that’s completely absent from the image going to the right eye, and vice versa. Each lens is precisely tinted to let only one of the images through, even when the two images are superimposed on a screen or in a photographic print.

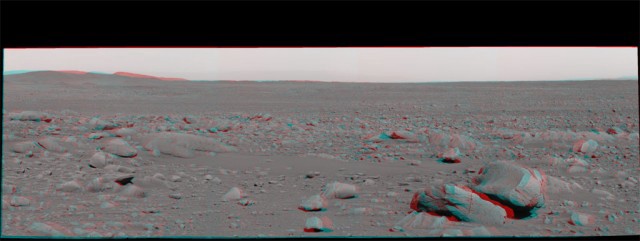

Since it’s color-based, anaglyph tends to garishly distort the hues of full-color subjects. But if the images to be conveyed are black and white, the anaglyph process doesn’t make much difference; each eye will see a monochromatic picture, and the brain can merge them effectively. Anaglyph 3D has enjoyed a DIY renaissance in the Internet era, because it can be created fairly easily with a pair of cameras and some free software, it can be displayed on any computer monitor, and it can be viewed with cheap paper glasses (you can order a free pair here).

There’s now anaglyph 3D content galore on Flickr and YouTube. NASA has even released some remarkable anaglyph images taken on the surface of Mars by paired cameras on its rovers.

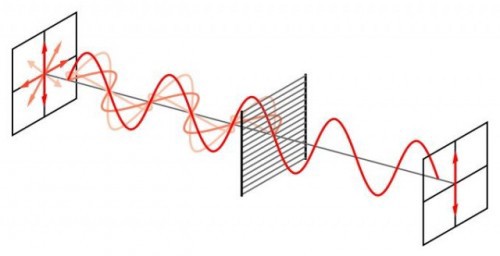

But anaglyph glasses are useless in a contemporary movie theater. Polarization has been the preferred 3D theatrical projection system for over half a century (with RealD’s digital version being the current market leader). Polarized 3D was invented by Edwin Land, father of the Polaroid camera, and uses lenses which invisibly align light waves in one of two different directions. Two pictures, each projected in differently-polarized light, are combined on a screen, and the left and right lenses of the appropriate glasses sort the images out for each eye. Polarized 3D requires a special filter on the projector, and a reflective metallic screen, but its accurate color rendition and the low cost of the glasses make it Hollywood’s choice.

The growing market for 3D television sets is dominated by active shutter technology, which displays left-eye and right-eye images in rapid alternation, instead of simultaneously. Viewers wear battery-powered glasses with liquid-crystal lenses, which receive a timing signal from the TV. The left lens goes black when the screen displays the image for the right eye; then the right lens goes black and the left lens become clear just as the left-eye image appears. In theory, this happens so many times each second that it’s imperceptible.

I recently watched the movie Tron: Legacy, and part of a college football game on ESPN’s 3D channel, on an active shutter television, and it all looked pretty good. However, rapid motion or panning sometimes creates a noticeable out-of-synch flickering effect. And you have to have a very big screen (and sit close to it) to experience truly immersive 3D. The glasses are the most cumbersome part of the system: they cost $100 a pair, are much heavier than polarized or anaglyph glasses and must be recharged periodically.

5. WINDOW VIOLATIONS AND OTHER CRIMES

All the technology involved in stereography means there are plenty of things that can go wrong. Many bad 3D movie experiences result from material that’s improperly shot, processed, edited or projected.

Every type of 3D system sends a slightly different image to the left and right eye. But when the differences are too great, the brain can’t resolve them into a realistic, fully dimensional view, and the magic won’t happen. Normally, the two cameras used to capture a stereo image should be about as far apart as a person’s eyes, and pointing in the same direction. If they’re spaced wider or closer than typical eye separation distance, objects will look either smaller or larger than normal. (This can be interesting, if it’s a desired effect. Here’s an image I took with cameras spaced a foot apart; everything looks strangely miniaturized.)

Images also must be properly aligned. If the vertical alignment is off, the eyes will constantly strain to correct the problem. The horizontal alignment is just as important: it controls how close or far away objects appear. If the nearest object to the camera is perfectly aligned in the left and right images, it will seem to be just behind the screen. If more distant objects are aligned, they will appear at screen depth, and closer objects will seem to project out in front of the screen.

This effect, too, is sometimes desirable. But it quickly becomes gimmicky, then unpleasant, when overused. And it goes completely awry when an object appears to float out in space, but is also cut off along one or more edges of the screen — a so-called window violation. The brain can’t make sense of the mismatch: is the image in front of the screen or behind it?

Yet another alignment-related issue is ghosting, when the image intended to be seen by one eye is faintly visible to the other eye. Ghosting objects appear to be doubled, a distraction which can ruin the 3D effect if severe enough. This happens when the image separation technology — anaglyph, polarized or other — isn’t working as well as it should for some reason.

Other problems occur when filmmakers don’t understand the unique properties of the 3D medium. It’s been said that 3D “wants to be slow”: because the eyes and brain need a little more time to figure out the spatial geometry of each shot, the pace of the editing needs to be more leisurely. A frenetic music video or action movie shot in 3D will become unwatchable if the cuts are timed at the same speed as they would be in 2D.

Then there are the tricky issues of depth and focus. It’s common in “flat” films to see shots where something or someone is extremely close to the camera, with everything else very far away. Usually either the foreground or background objects are in focus, but not both. In a 3D film, making anything deliberately blurred can confound our optical reflexes: we’re used to choosing how far away to direct our visual focus, rather than having that choice forced upon us.

The worst 3D experiences result when a film is shot in the ordinary way, with a single camera, but then converted to 3D in post-production. This “fake 3D” requires digital simulation of a second viewpoint, and it’s hard to do well. Rush conversion jobs on Clash of the Titans and Alice in Wonderland, both released last year, presented audiences with what looked like cardboard-cutout characters in front of flat backdrops. Studio decisions to add 3D to these movies after production, and to do it cheaply, may have done more to stoke a revolt against the medium than anything else.

Given sufficient time and money, 2D-to-3D conversion can be done successfully; this summer’s Captain America is one example, and the forthcoming re-release of Titanic looks to be another. But nothing beats shooting with two cameras to begin with. And plans to convert more old films to 3D stir up bad memories of Ted Turner’s ill-starred attempts at colorizing black-and-white classics.

Ultimately, 2D and 3D movies demand different kinds of visual logic. If directors, cinematographers, editors and animators don’t understand this, they can’t make the right choices to create good stereoscopic experiences. Right now, thousands of film industry professionals are on a steep learning curve. The question is: Will enough of them become proficient at 3D filmmaking before audiences grow tired of suffering through their mistakes?

6. UNNATURAL AFFECTIONS

Walter Murch’s critique of stereography, cited by Roger Ebert, is strictly correct as far as it goes: the human visual system did not evolve to conjure depth out of a flat image. But what Murch fails to acknowledge is that we do stuff we didn’t evolve to do all the time. In fact, our brains have turned out to be pretty good at reading three dimensions into a 2D picture — we do it even when we look at a non-stereoscopic photograph or video. And as Werner Herzog reminded us in his graceful 3D documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the human race has been creating flat images with the appearance of depth for tens of thousands of years. Stereography is just the latest, most elaborate form of this illusion.

We’ve all spent countless hours looking at conventional flat photo and video images, and are very skilled at interpreting them. But most of us have spent only a few hours, at most, watching artificial 3D… and as discussed above, the skill sets and techniques required to produce and reproduce quality stereoscopic images are still not all that widespread. It’s not surprising that we aren’t as good at “reading” 3D yet. But it would be foolish to believe that we can’t get better at it.

It was shortly after watching Avatar that I decided that a no-budget music video I’d been planning to shoot would be even better in 3D. I procured a pair of identical cameras, mounted them on a crossbar and started experimenting. I still haven’t finished the video, but I’ve shot thousands of stereo images (many of which are on view in anaglyph format here), and joined a worldwide community of professional and amateur stereographic enthusiasts (some of whom I’ve met through the New York Stereoptical Society).

I’m fascinated by 3D not only in spite of, but because of its artificiality. There’s an element of sorcery at work when a simple pair of glasses allows a flat screen to become a portal into another realm of depth and solidity. I suspect that on some level, many critics of 3D aren’t just upset about eyestrain or high ticket prices: they are actually unnerved by the medium’s uncanny power. Denouncing stereography as a fraud, a gimmick or a failure may be a way of covering up anxieties about its disturbing intensity. Legend has it that primitive tribesmen, confronted with the cameras of visiting anthropologists, railed against them as boxes for capturing souls. That Luddite instinct is still there, even in many of us convinced of our own sophistication. There may also be a kind of snobbery at work: 3D may be seen as too viscerally enjoyable, too much of a thrill ride, to possess the rigor and obscurity of “real art.”

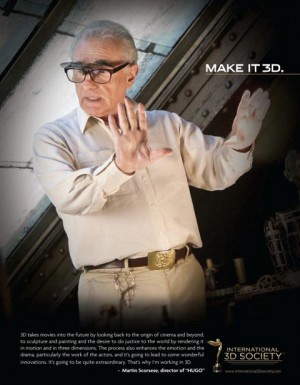

The truth is that 3D is still a very young medium; the world’s most acclaimed living filmmakers have only just begun to explore it. On the heel’s of Herzog’s cave-art documentary, Wim Wenders has released Pina, a celebration of modern dance choreography. In the realm of the fantastic, Martin Scorsese’s Hugo is rapidly winning converts (even 3D grouch Roger Ebert), and, in the words of reviewer Ryan Lambie, stands out as “a reminder that cinema is and always has been an optical illusion, a trickster’s routine as intricate as a clock mechanism.”

Steven Spielberg’s first 3D outing, Tintin, produced with the same motion capture technology as Avatar, is getting mixed reviews for its formulaic qualities — but that’s nothing new for Spielberg. Francis Ford Coppola is showcasing Twixt, an experimental genre film that he remixes in real time at each screening. (This is not Coppola’s first dalliance with 3D: he directed Disney’s 1986 Michael Jackson vehicle Captain Eo, and shot 3D nude sequences for a German sex comedy called The Bellboy and the Playgirls way back in 1962.) At the same time, Ridley Scott is readying Prometheus, his 3D prequel to Alien. Scott, a former cameraman with an incomparable visual sensibility, is so smitten with stereography that he says he’ll never make another movie in 2D.

Outside of the multiplex, artists are using increasingly accessible 3D techniques for their own purposes. Claudia Kunin is transforming old family photographs into surreal stereoscopic animations. Paul Johnson is using the neglected lenticular process (familiar from novelty postcards, with images that change as they tilt) to compose whimsical but subtly unsettling Man-Ray-esque 3D shadowgrams. Maya Zack recently used mural-sized anaglyphic prints to recreate a Holocaust survivor’s prewar Berlin apartment at New York’s Jewish Museum.

To be sure, there will always be things we just don’t need or want to see in 3D. The development of motion pictures, color and sound hasn’t rendered us incapable of appreciating the art of black-and-white still photography. For those who prefer to steer clear of stereography altogether, many 3D films are now shown in 2D as well; where they aren’t, a pair of 2D glasses will flatten out the experience.

But for all the talk of 3D backlash, I’m increasingly certain that the golden age of stereography is only just beginning. Tens of millions of 3D TVs have been sold thus far. New cameras and phones allow anyone to take and share stereo pictures and videos. And on the horizon is the holy grail of 3D: autostereoscopic systems that work without glasses.

These displays employ the same principle as lenticular images: a fine structure of vertical lenses or lines embedded in the screen ensures that each eye sees a different view. The Nintendo 3DS currently uses this technology on a small scale. But a recent consumer electronics convention in Japan featured a 200-inch autostereoscopic screen. The setup weighs half a ton and requires dozens of projectors, but it’s a sure bet that better and cheaper versions will be in movie houses, and living rooms, sooner or later.

Cynics and grumblers will continue, for a few years at least, to dismiss 3D as unworthy of serious attention. But at this very moment, kids watching Up, or playing Call of Duty 4 on a PlayStation 3D display, are rewiring their young brains to understand the medium in ways we can barely imagine. Somewhere among them, the next Orson Welles or Stanley Kubrick is beginning to dream up new worlds, with both eyes wide open.

Maximus Clarke makes pictures and sounds in Brooklyn, and tweets at @bookofsand.

Images from top: Converted Avatar still courtesy of James Cameron’s Avatar wiki; stereoview of Broadway courtesy of the NYPL Digital Gallery; Twain photo courtesy of Abuduzeedo; converted Nightmare Before Christmas still courtesy of animator Joel Fletcher; subway photo by the author; Mars Rover photo courtesy of NASA; wire-grid polarizer illustration by Bob Mellish, via Wikipedia; photo of CrystalEyes shutter glasses by Dave Pape, via Wikipedia; 3D hyper photo by the author; image from “Barbie Dreams In 3D” by Paul Johnson.