A Scenic Tour Of Toxic Sites Across America

So we’ve all scanned Google Earth for the Indian ship-breaking beaches, or the rows of planes in aircraft boneyards, or the abandoned and overgrown town of Chernobyl. But toxic, garbage-y sites aren’t always limited to exotic, remote locales — sometimes they’re right past our backyards. Sometimes they’re even under our backyards.

Osborne Reef

In 1972, two million tires, clustered into groups with metal clips, were dumped into the ocean in a two birds/one stone attempt to clean up the landscape encourage natural reef growth. Instead, the well-intentioned ecologists created a 50-foot diameter dead zone a mile off the coast of Fort Lauderdale. Area marine life was forced away by the completely inhospitable environment. Additionally, the cheap metal of the clips soon corroded away in the salt water. The tires broke free from the bundles and, tires being tires, they became mobile. Soon tires were washing up after every tropical storm and hurricane on shores from North Carolina to the Florida Panhandle. There have been removal projects on and off since 2001, but at a cost of $17/per tire it’s a slow process. By the way, the last tire in was a ceremonial gold-colored beaut dropped by the Goodyear Blimp. I wonder if they’ve dredged that one up yet?

Fresno Sanitary Landfill

Congratulations, Fresno! You’re the home of the first modern landfill, the only one to be declared a National Historic Landmark. Opened in 1937, the Fresno Sanitary Landfill accepted an average of 16,500 tons of municipal trash per month until it closed in 1987. Today it’s a Superfund site — but the human exposure levels are low enough for baseball fields to sit on the same block. Though I’d steer clear of that pond.

Puente Hills

The largest landfill in the United States is sandwiched between two of the most stereotypically Calfornia-sounding towns in existence: Avocado Heights and the City of Industry. It is located, as you could reasonably conclude from those names, just outside of Los Angeles. Puente Hills, aside from being a giant mountain of garbage and accepting your dirt for free between the hours of 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. (where else are you going to put your dirt, huh? On the ground?), channels the gas produced decomposing trash into power for the equivalent of 70,000 homes/yr. The Center for Land Use Interpretation, an LA-based research organization, organized archeologically minded tours of the dump as a way of showing the public what happens to their garbage once it leaves their curb. CLUI summarized the trip in a 2009 edition of their newsletter, Lay of the Land — trust me, it’s a must-read.

Munisport

Munisport. That sounds fun, right? Like a rec center or something. Nope! This is a column about trash heaps, not foosball. Located in North Miami, Munisport actually had a short life as a landfill, 1974 to ’80, but that was enough time for a a massive underground ammonia plume to form, threatening Biscayne Bay. Poison in the groundwater could only keep the developers away for so long. Twenty years later, a 6000-unit condo project went up under the name Biscayne Landing. Being a known contaminated area, few units were sold, and when you add in the recession, well… The project was declared a 100% loss earlier this year. A pair of near-empty towers sit on the waterfront, most potential residents scared away by features like the horrific odor that emanates from the ground after a rainstorm. Does anyone know if “CSI:Miami” has done a show on this? If yes, please tell us the Caruso quip in the comments?

Valley of the Drums

And you thought this little tour was going to be all California and Florida. Oh scenic Bullitt County, Kentucky! Home of bucolic rolling hills, bluegrass music, UPS’ big sort, and up until recently 23 acres of the finest leaking industrial waste drums this side of a Sierra Club scare ad. Seriously. Look at this place. It was an uncontrolled dumping ground for all kinds of industrial waste for years before the authorities paid it any mind (which they did in the late ’60s, when it caught fire). Though the site once held more than 15,000 leaky drums, careful cleanup efforts have reduced it to only a few dozen today (they’re still finding more in neighboring Jefferson Memorial Forest, which, oof!). Many of the drums contained (and thus, leaked) latex paint, which over time has dried to form curious modern fossils. View those and a variety of other terrifying photos in this retrospective slideshow, published by the Courier-Journal in 2008.

Point Comfort

This is not an infrared image. It’s not a scene from the Mars rover. It’s not the Crayola harvesting ground. It’s not the Hungarian sludge, either — although that’s not a bad guess. It’s the Arcoa aluminum plant just outside of Point Comfort, Texas, and the dull red hue comes from the waste product created by extracting aluminum from bauxite ore. That massive slide in Hungary was caused in part by that plant’s practice of storing the waste as mud. Here in the United States, the waste is intentionally dried out, which means that dust storms in that area of Texas are rust colored. Which sounds almost picturesque, until you notice that it’s eating away the paint on your car and then wonder what it’s doing to your lungs.

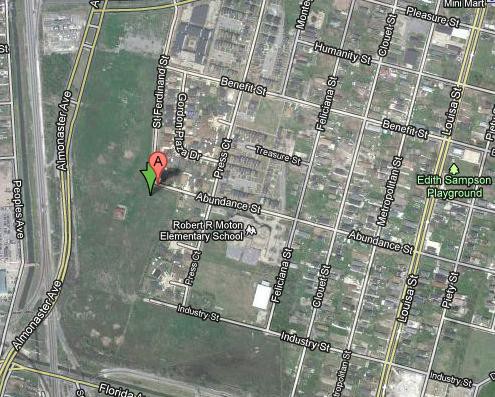

Agriculture Street Landfill

For every waste site that tries to camouflage themselves under an innocuous name — Love Canal, Rolling Knolls, uh, Wilmington International Airport — you have a place like Agriculture Street Landfill, a forgettable name for a briefly forgotten place. Since the early twentieth century, the New Orleans open-pit-style dump (not a controlled landfill, such as the aforementioned Fresno site) was colloquially called ‘Dante’s Inferno’ because of its frequent uncontrollable fires. It closed in the mid-’60s and was out of the public mind just long enough — a decade later when some bright folks covered it in sandy soil and built up a residential neighborhood including an elementary school. The EPA initially declined to get involved, but was forced to declare it a contaminated area in the wake of abnormally high cancer rates among residents. In some cases, trash was buried so shallowly that it was uncovered by citizens trying to construct pools and fences. Talk about Not In My Backyard!

Beltsville Agricultural Research Center

Here’s a question that probably won’t get a yes from many of you: Have you ever taken the B30 Metrobus from Greenbelt to BWI? If you have, you’ve passed right through a prominent Superfund site without even realizing it (okay, fine, maybe you realized it, overachiever). If you haven’t had the pleasure, let me share that the Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center is a 6600 acre US Department of Agriculture testing ground. Composed of farmland and crisscrossed with streets with names like “Animal Husbandry Rd and “North Dairy Rd,” here is where the USDA grows test crops and researches plant genetics ad food animal production along with a variety of other practices. What has qualified it a Superfund site, however, is the chemical testing that goes on here, which contaminates the groundwater. Many of those chemicals originate on, you guessed it, Pesticide Road.

* I mean that in the nicest way, of course. I’m a member of the Sierra Club, John Muir is a national hero, and their scare ads on the metro are hi-larious.

Victoria Johnson would love to visit the Center for Land Use Interpretation someday.

Osborne Reef photo by Navy Combat Camera Dive Ex-East; Valley of Drums photo courtesy of EPA. Other aerial images courtesy of Google Maps.