A Conversation With Writer Scott Raab

by Sean Manning

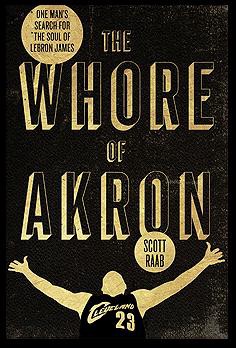

Scott Raab’s new memoir The Whore of Akron: One Man’s Search for the Soul of LeBron James isn’t really about basketball. It’s about addiction and sobriety, marriage and divorce, childhood and parenthood, loyalty and autonomy. In 15 years at Esquire — and five years at GQ before that — the 59-year-old Cleveland native has, as he writes in the book, “shared cunnilingus tips with Robert Downey Jr., got tattoos with Dennis Rodman, once smoked a bone with Tupac, twice did nothing with Larry David, and visited with Phil Spector in his castle in Alhambra three times, all without gunplay…[and] even went to Bill Murray’s house once for an Oscar party.” He’s also responsible for hands-down the most insightful and exhaustive reporting on the rebuilding of the World Trade Center. We spoke at his home in Glen Ridge, New Jersey.

Sean Manning: What do you have against the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum?

Scott Raab: On one level what I have against it is the Cleveland that I love most only exists in my mind, because things fall apart and the center cannot hold and all that. And so the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame sits where the East Ninth Street Pier used to be and Captain Frank’s Lobster House. And I had many, many hours of contemplation, in altered states of consciousness and otherwise, on the East Ninth Pier. And same with Captain Frank’s. That was a place where my mother, who was a divorcée, as they used to say back in the ’60s and ’70s, where her boyfriends if they had a good day at the track would take us. And later, many years later, when the girls who danced at the Crazy Horse Saloon got off work at two or three a.m. and wanted a bite to eat. And the fact that it’s a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in and of itself seems oxymoronic. The idea, “I’m gonna go to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and look at Joey Ramone’s sneakers, his black high tops. I’m gonna go there and see Rick Nielsen’s 117th guitar.” You know, go to the fucking art museum. Go to Severance Hall and listen to the orchestra. I think the Hard Rock Café has more validity as a concept than a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. If you’re gonna hand out blunts at the door, then okay. Not for me anymore. But seriously, if you’re gonna separate and deracinate and squeeze all the blood out of the rock and roll experience? I don’t have any time to waste.

Speaking of blunts, you once got high with Tupac.

That was a Mickey Rourke profile, at a time when Mickey’s career was down, down, down, down the drain. And so he was making a what turned out to be direct-to-video movie in Brooklyn called Bullet, directed by Julien Temple. And Tupac was one of the costars. And everywhere that Tupac went, you know, a bag of weed came out and Tupac would roll ’em up and smoke ’em. We were at a dance club. It’s not like he and I sat down and smoked together and had a long conversation about lyrics. But yeah, I said, “You mind passin’ that my way?” So I consider that getting high with Tupac.

The NBA season ended the first week of June —

June 12th was the date of Game Six.

And the book’s publishing date was November 15. How did you manage such a tight schedule?

The HarperCollins people — David Hirshey and Barry Harbaugh, the two editors — they did a really great job of helping me walk that tightrope. The manuscript delivery date had moved up, from August 15 to July 15. And I had a big deadline for Esquire: the tenth anniversary of 9/11. I’ve been writing about the rebuilding since 2005. This was the seventh feature story. And this one, because it was the tenth anniversary, and because they managed to get the memorial open on time, to at least allow the families to finally engage with a finished memorial — or mostly finished memorial — it had to be a good, long, juicy magazine feature for the magazine that I thank goodness every day that I have a job for. So the deadline for that was July 15, the issue starts closing. So I took a condo in the city, not that far from Midtown, to spare my wife and son the agony of my agony.

I think the Hard Rock Café has more validity as a concept than a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. If you’re gonna hand out blunts at the door, then okay.

Being close, a couple blocks away from HarperCollins’ office, let me go in there during the day and work on the early chapters that I’d already submitted. At least half the book was already there but needed some reworking and smoothing out in terms of voice and theme. And at night I would go back to the condo and write, push through the ending of the book. I worked around the clock. I would take a nap, you know, after overeating, until eight or nine or ten p.m., and I’d write through the night. Then I’d go into the office. It was hard. To go back and start YouTubing some of the most dire or tragic… I mean, I know it’s not war, famine, pestilence. I know it’s sports. But to see the Browns team in ’95 at the last home game when everyone knew they were leaving and the fans were tearing the stadium apart. To think about that and the way LeBron left, and I’m sitting writing, and I’m weeping. I mean, I’m crying while I’m writing. I could’ve taken six more months or two more years but I don’t know if that would’ve actually helped. Because what happened in the writing, given the schedule, was really cool. It was a sense of letting go of the stuff in a way I’m not always able to do in a magazine cycle, because I want every sentence to be perfect. And sometimes a piece suffers for that. But because of the time pressure I couldn’t really indulge myself that way. I had to get honest and real as quickly as possible.

The jacket copy of the book describes you as “a last vestige of Gonzo journalism.”

You know, it’s funny, because it’s not like I’m that much younger than Hunter S. Thompson would be had he not blown his head off. But I did come up at a time when… I wasn’t a journalism-school student. Thank God they didn’t even have J-schools, as far as I know, back then. So when I came up, you know, I started college in 1970, and I didn’t stay long. Took me 13 years on and off to get a bachelor’s degree. To the extent I was aware of journalism it was the National Lampoon, which was a take-no-prisoners, very funny monthly. It was absolutely scandalous. Now they probably couldn’t get away with it anymore than “Saturday Night Live” could get away with lecherous babysitter skits. And Hunter S. Thompson was filing stories for Rolling Stone. So my idea of journalism wasn’t based on New York Times pyramid-style reporting. It was based on kind of balls out… But I don’t think I was ever conscious, “I’m a Gonzo journalist.”

I ran into a guy in Miami the same week I got my credential taken away [for a series of negative tweets about LeBron James] whose son was wearing a vintage “Witness” tee shirt. So I said to the kid, “Are you a LeBron fan?” He goes, “I used to be.” I said, “Where’s your dad?” His dad comes over, we’re talking, he introduces himself. “Robin Thompson. You know, my uncle was Hunter.” I go, “Get outta here.” He goes, “Yeah, yeah, yeah. My name’s Davison Thompson. My father was Davison. I’m the third, and Hunter was his brother.” He didn’t wind up in the book. That was the editor’s decision. It just seemed a little too contrived. You know, to go, “I’m in Florida. I got my credential taken away. Mr. Gonzo Gonzo. I meet Hunter S. Thompson’s nephew, who’s a total Cleveland fan and LeBron hater, going ‘Just tell our story, man.’” And he’s not a bullshitter. I’ve researched the guy. That’s Hunter Thompson’s nephew.

In the book, you reference Frederick Exley, who wrote A Fan’s Notes. When did you first encounter his work?

I don’t remember the first time. Because until I got sober in the mid-nineties I was loaded every day for 20-plus years. So the first time I read A Fan’s Notes, I’m not sure I could tell you within five years when it was. That wasn’t exactly a paradigm but it was always a book that you carry around inside you. And Exley was a guy like Bukowski. The quality of their work was, in an ironic or even negative way, was kind of a justification for going, “Yeah, you know, I’m a hapless fucking alcoholic. I’m a fucking drug addict. I know it. I don’t give a shit. ’Cause I’m a writer.” And, you know, that didn’t work in my favor in terms of building any kind of career. And what I’m left with, including with Hunter S. Thompson, is the sense that they wasted a lot of their talent. They’re not the only ones. They’re just the most famous of the guys who did that, who could’ve been much more productive for much longer. Both as artists and as humans.

You and Exley have something else in common: the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Him as a teacher and you as a student.

I wasn’t there when he was there. I went back to Cleveland State the last time and was really determined to finish up. I was an English major. I was in my late 20s. At that time I was thinking either Ph.D. work in English or something like American Studies. But I had always been a writer from an early age, always took writing seriously. I wrote poetry. “Doggerel” would be the right word. I wrote, like, sports poetry when I was twelve, thirteen years old. There were creative-writing courses at Cleveland State. I had taken a verse writing course in the mid-’70s. I had dropped out after that. But I took poetry seriously. I was the co-editor of the Cleveland State University literary magazine. And so when I was finishing up, I was writing short fiction. And I was really encouraged by the professors there. So when it came time to apply to graduate school, I applied to the Stanford writing program, I applied to U. Cal-Irvine, and I applied to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. And I was turned down by Irvine and Stanford. And the Workshop, which has fifty fiction writers and fifty poets, had room. At least that’s how it felt; not like I just blew them away with my unbelievable talent but that they had enough room, they cast a wider net and I was lucky enough to be part of it.

You gonna send query letters to the New York editors? You gonna pound the pavement in Manhattan going, “Hi, I’m a Cleveland State University Viking. My professors think I’m super. Will you take a look at my work?”

One of the great drunken sprees of my life was the night I got that letter. I think it was February 2, 1984. I have the letter somewhere. And I knew that this was a big stinkin’ break, that a Cleveland State guy could be a really good writer. What are you gonna do? You gonna send query letters to the New York editors? You gonna pound the pavement in Manhattan going, “Hi, I’m a Cleveland State University Viking. My professors think I’m super. Will you take a look at my work?” But then you get to go to Iowa City and you know that there’ll be people from Yale and Sarah Lawrence and Harvard and everywhere. And I was already 32.

When I went there the workshop classes were on the fourth floor of the EPB — the English-Philosophy Building. I was so nervous, I walked every floor before I could collect myself enough to go into the Workshop office to find out about where things were and was there housing. It was a big deal. Whereas a lot of those folks, my classmates, were in their 20s. They’d never done anything but go to school. Their expectations of success were assumed. It was a part of their mindset. Early that first semester, there was a visiting editor. You always had visiting agents, visiting writers, visiting editors. Ted Solotaroff, may he rest in peace. You know, New York guy, one of Philip Roth’s editors and friends. And he’s giving a public workshop. And you submit stories. See if the visiting star is gonna do your story, you know? And my first workshop story was one of two chosen for the public workshop. And I went, and there were all my classmates, both the first- and second-year students, most of whom I didn’t know. And there was everyone else — a lot of Workshop grads who’d just stayed in Iowa City. And he did my story first. And you could tell he front-loaded in the first minute everything that he might say that was positive about the story. And then he spent, really, half an hour pointing out how amateurish it was, how poorly written it was, how lacking it was. And it was a great experience for me. Because you had the first-year students, the few that I knew, looking at me with that look, that “Are you okay?” look. And that actually went on for a couple weeks, with people going “Are you okay? Are you okay?” And the second story, it was a second-year student, and he used that one as the good one. You know, “the before and the after.” And I went to a Burger King with my then-wife. We had sat through this whole thing making little notes, like “Uh-oh” and “Can you believe this?” and whatever. And we went to the Burger King and I said, “Fuck, I ain’t going back to Cleveland. Bring it on.” It’s not like I didn’t rework that story and sell it eventually. Because I did.

You mentioned Philip Roth. You profiled him last fall for Esquire and earlier this year participated in a Roth celebration co-sponsored the National Book Critics Circle and the Center for Fiction. What’s your favorite book of his?

I have a few, you know, because there have been different phases in his career. Portnoy’s Complaint hit me at a certain age, seventeen, when I didn’t just relate to the subject matter and the content but as a young writer said, man, anything is possible, you can go anywhere if you do it with confidence and authority. And I think Sabbath’s Theater is a very great book. Operation Shylock, to me, is a wonderful book, although I don’t know how many people would rank it with Sabbath’s Theater and Portnoy. The Zuckerman novels. Even his recent novels, which I know a lot of people have dismissed, different ones, as trivial and unworthy and this, that, and the other thing.

How about Harvey Pekar? In the book, you call him “the finest writer Cleveland has ever produced.”

You know, Pekar… If they hadn’t made that movie American Splendor, the people of Cleveland would still go, “Well, if you spent your life trying to produce stuff here you must suck.” And to me, he’s Chekhov. I mean, I know he’s always worked as a graphic novelist, comic-book writer, but that prose is really, really spare, riveting, unadorned brilliance. And it doesn’t reach for anything except reality rendered as artistically as one honest voice has rendered it. Joyce Brabner, his widow, is trying to raise $30,000 on Kickstarter to create a statue of Harvey, because she knows the city’s not gonna do it. And that’s fine. You know, Cleveland has better things to do in terms of its schools and infrastructure than build statues to anyone. But to the extent I’ve studied the project, it’d be him essentially coming out from a comic-book panel, and the back would be slate so people could write on it. It would be great, wouldn’t it? I will continue to do everything I can to help make that shit happen. I owe him that, I owe her that, I owe Cleveland… I owe Cleveland a lot.

I know Roth was a dream interview. Who else is on that list?

Van Morrison. Brando was on that list. When I interviewed Sean Penn, and we got along great, kept in touch a little bit, I kept pushing Sean to try and get me with Marlon Brando. Of course, it’s a little too late now. Dylan. Woody Allen.

Favorite Dylan album?

Probably Blonde on Blonde. I mean, I’m old. These albums…When I was in my early 20s and these guys were putting out albums…You know, it’s hard to, when you connect with something at that age… It’s like Springsteen. The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. It’s not that I don’t love Born to Run or The River or Nebraska or all that. But you connect with certain albums at certain times in your life and it’s like you’re never again gonna not buy whatever that artist makes but you’re probably never again gonna feel the way you felt when you were just on fire with the sense of discovery.

Interview condensed, edited and lightly reordered.

Sean Manning is the author of the memoir The Things That Need Doing and editor of several nonfiction anthologies, including Top of the Order: 25 Writers Pick Their Favorite Baseball Player of All Time, which featured a contribution from Scott Raab.