Punk Love For The Electric Prunes

by Peter Bebergal

In 1983 I sat cross-legged on the floor of my room, headphones tight against my ears, and placed a record on the platter. The stack of albums next to me was a prime collection of early American hardcore punk — The FUs, Minor Threat, Youth Brigade, 7 Seconds, Crucifix, Negative Approach — but the vinyl that eagerly met the needle was something different.

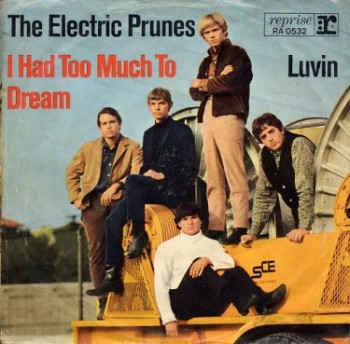

By the time I laid my teenage, resin-stained fingers on it, “I Had Too Much to Dream” by the Electric Prunes was someone else’s dream long gone by. Released as a single in 1966 and later on the band’s first full length album The Electric Prunes, “I Had Too Much to Dream” reached #11 on the Billboard chart. The song prefigures what would become a dominant psychedelic vibe in pop music, but it wouldn’t be until 1967 when psychedelic rock owned the airwaves with songs like “White Rabbit,” “Light My Fire” and “Purple Haze.” “I Had Too Much to Dream” was rooted in garage rock, which in 1966 was the sound of the burgeoning counterculture: The Troggs, Count Five, ? and the Mysterians, and, of course, The 13th Floor Elevators. These were the bands that would influence the early punks of the ’70s: Iggy Pop, the Ramones and Patti Smith. The hardcore punk of the ’80s might have sped things up a bit, but you could trace a lineage directly from Minor Threat back to the Electric Prunes.

Rock history was kind to what might have been a forgotten one-hit wonder. In 1972, the definitive collection of psychedelic garage rock, Nuggets, used the song as is opening track. As that collection showed, psychedelic rock need not be all sitars and long strobing jams; it could be angry, too. And there was no better energy for a teenage punk looking to blow his mind.

Like almost everyone who played the song over and over again until even the scratches in the record became familiar, mine was a romantic love, born of a deep desire to find meaning beyond the conventional, beyond the mainstream, and beyond what I thought even music could be capable of. In the early 1980s, the Grateful Dead and the ’60s rock played on oldies stations were the only things that smacked of psychedelic. But that was music for old people or the young stoners with their collarless brown leather jackets and Timberland boots. It might be good when you were stoned, but it didn’t contain anything beyond a feeling of feelin’ good. Listening to Cream and Iron Butterfly wasn’t rebellion; it was smoky nostalgia. Drugs and music were a catalyst for rebellion, not for staring at the inside of your eyelids. For hardcore punks looking for music that would shoulder anti-authority sentiment and LSD imaginings, the garage psych of “I Had Too Much to Dream” was just bold enough and, even better, it didn’t sound anything like Jerry Garcia.

The members of the Electric Prunes — Joe Dooley, James Lowe, Michael Weakley Ken Williams, and Mark Tulin — came of age listening to surf music and the bands of the British Invasion. It was music swimming in reverb and whimsy, but edgy enough to lead the way. One day, jamming in their actual garage, a real-estate agent passed by, heard them and introduced them to a producer friend. It was dream come true. Once the young musicians were in the studio it was clear they could play their instruments, but the record producer that discovered them had no confidence in them as song writers. A writing team was commissioned to write the songs. They accepted their fate as a record company assemblage, but soon figured out how to bring put their own signature on it. The Prunes found themselves caught up in a whirlwind of marketing and publicity that manipulated an earnest, if sometimes delusional, mushrooming psychedelic counterculture. The Electric Prunes were just a bunch of teenagers, and with teenage spirit still made something original.

“I Had Too Much to Dream (Last Night)” starts with a killer opener, a guitar riff played backwards that grows in velocity towards hyperspace and then stops short at the ringing of a gently tapped triangle. Soon the pounding drums and gruff vocals turn it all into rock ’n’ roll again, but it is a rock born of psychedelic storm clouds. The song, as lysergic as anything else at the time, was amateur with a raw energy that prefigured punk. And despite its Top 40 aspirations, “I Had Too Much to Dream” keyed perfectly into the acid-fueled visions of the sixties.

I spoke with the bassist Mark Tulin by phone in 2010 while researching my book, Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic American Boyhood, an obvious homage. (Tulin died earlier this year in a scuba-diving accident as part of an underwater cleanup effort in California.) I asked about the intention that had gone into the recording of that song, how much acid had played a role, and how much he and his bandmates thought they were going to turn on the world. As it turned out, none of these things were factors. The band rarely even got stoned. As Tulin told me, “I just wanted to play music and the only way to do that was to be in band. I didn’t have a grand statement. The most important thing on my mind would have been, ‘Can I get a date?’”

“Too Much to Dream” was released as a single a year before 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival secured a legitimate place between counterculture and mainstream for psychedelic rock and the hippies that listened to it. The single was timely. The press hadn’t yet called the burgeoning drug-inflected pop scene ‘psychedelic.’ The Electric Prunes didn’t know much about the music industry yet, but they knew enough that even being a little bit different could be a good thing. “We didn’t try to fit into anything and consequently fit in between everything,” Tulin recalled.

The music historian Elijah Wald has suggested that the Beatles ruined rock by disconnecting it from its blues roots and turning it into something manufactured and produced. But it could also be said they ruined psychedelic rock by disconnecting it from its youthful garage origins. The Beatles made psychedelic sounds for adults, but it was kids who were picking up guitars in their parents’ wood paneled basements and hammering out three fuzzy chords. As Tulin tells it, even the Electric Prunes felt the weight of the Beatles: “Sgt. Peppers set the gold standard for what you should be doing in the studio and took an edge off garage rock. They upped everyone’s sophistication level.”

But along with an emphasis on the studio and sophistication came the business of music, the managers and the producers. The Electric Prunes were given outfits to wear and had to wear them under orders at some television appearances (Tulin recalled burning these outfits one night outside a hotel — you could tell from his voice that it was a fond memory). They just wanted to make music organically, from the original place that led them to their instruments. And that place was not the airy spacey psychedelic motif, but the anger of garage rock. Even more to the point, the drug experience didn’t drive their music. “If I got too high when I was playing I internalized and it might be grand, but it didn’t sit with what anyone else was playing,” Tulin said.

Sitting in my room that day, I gleaned a thousand points of light from that three-minute song. It distilled for me a mostly scattershot belief into a hope that the ’60s counterculture and the ’80s punks were not so different, that music could change the world. Add a little LSD to the mix and you might even change the mind of God.

Punks loved to put up their middle fingers to the hippies, but we owed them just about everything. Even our beloved fanzines were a pale shadow of the ’60s underground newspapers. We refused to admit it, but they had something to fight for. They hated the Vietnam War because they watched their friends and relatives come home in bodybags. We hated Ronald Reagan but we didn’t even know why. There wasn’t a real counterculture to contain or support a teenager straining (and overreaching) for meaning. Even the punks were fighting amongst themselves.

Despite its energy and sincerity, punk was often an empty gesture, raising fists against abstractions and Def Leppard. What I didn’t know was that “I Had to Too Much to Dream” was as manufactured as anything I was railing against in the ’80s. “Too Much to Dream” was less a song than it was an icon. But icons are mostly empty except for what we impose onto them. What I heard in the music, in that fabled song “I Had Too Much to Dream” wasn’t real; it wasn’t a drug-fueled revelation, and the intention driving it was little more than messing around with guitars, meeting girls and going to parties — the surer purpose of rock.

Peter Bebergal is the author of Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic American Boyhood, out now from Soft Skull Press. He’s also on Twitter.