Celebrities And The "Rape" Of Photography

by Soraya Roberts

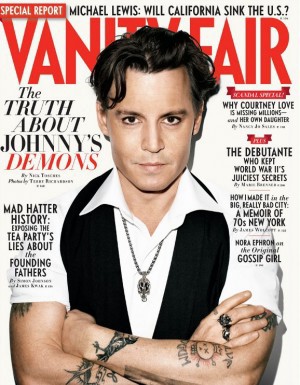

Johnny Depp took his reputation for eccentricity a little too far last week. Interviewed in the November issue of Vanity Fair, the actor appeared to let his guard down when discussing photo shoots with writer Nick Tosches, a long-time friend and a godparent to one of Depp’s kids. “Well, you just feel like you’re being raped somehow,” the actor said. “Raped. The whole thing. It feels like a kind of weird — just weird, man. Weird. Like you meet people and they say, ‘Can I have a picture with you!’ And that’s great. That’s fine. That’s not a problem. But whenever you have a photo shoot or something like that, it’s like — you just feel dumb. It’s just so stupid.”

Depp isn’t the first actor who’s had to apologize for comparing photography to sexual assault. Just last year, Kristen Stewart told Elle UK that seeing photos taken of her by the paparazzi felt like “looking at someone being raped.” It’s an extreme reaction to the medium, and one that Susan Sontag addressed in her seminal On Photography, in which she argued that, while images can be violated, the people on whom those images are based cannot. “One can’t possess reality, one can possess images,” she wrote. But in Hollywood, a world where image is everything, how do you tell where reality ends and image begins?

The answer is clearly not provided on the big screen. On the contrary. Interestingly, Depp uses the term “stupid” at least a couple other times in the interview. One of them comes when he’s describing his opposition to a staged cockfight in the upcoming film, The Rum Diary. Though the cockfighting scene reportedly looks real, the roosters were protected from killing each other with pieces of invisible monofilament (in accordance with American Humane Association regulations), a precaution he appeared to think detracted from the viscerality of Hunter S. Thompson’s original scene. “I think it was stupid,” he told Tosches. Extrapolating from that comment, Depp use of the term “stupid” suggests his aversion to false representation. Given his stated pleasure at being photographed by fans in his everyday life, it’s the falseness of the photo shoot and the poses associated with it that seem to bother Depp.

I

n this, Depp brings to mind Diane Arbus’ “freaks,” who remain some of the most extreme examples of the falsely represented. In On Photography, Sontag refers to the technique used by Arbus, famed documenter of New York’s marginalized (dwarfs, giants, transvestites, nudists etc.): “Instead of trying to coax her subjects into natural or typical position, they are encouraged to be awkward, that is, to pose. Thereby, the revelation of self gets identified with what is strange, odd, askew. Standing or sitting stiffly makes them seem like images of themselves.” In a similar way to Arbus’ subjects — whose real selves are undermined by the images the photographer wishes to present of them — Depp subverts his own persona and projects that of the various fashion photographers who shoot him for magazines. In this way Depp maintains the Hollywood illusion of himself as poster boy for celebrity eccentricity.

The photographer’s power lies not only in determining how his or her subject poses, but also in how the image is ultimately produced (cropping, editing, Photoshopping, etc.); as Sontag put it, “in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects.” Small wonder that Julia Roberts could tell American Photo in 2004 that she feels “stupid,” “goofy,” and “nervous” — like Depp — when being photographed and, in the same breath, say that when she handles a camera (as in the film Closer, in which she played a professional photographer), it “instantly makes you the coolest person in the room.”

Other celebs try to wrest control back from the cameraman. When I interviewed Shirley MacLaine a few years ago on the set of the TV movie Anne of Green Gables: A New Beginning, during our photo shoot, she chose the position in which she sat and dictated the light and filters the professional photographer was expected to use. Using a different tack, Lady Gaga caused a stir in March when she issued a release form demanding that concert photographers sign over to her the rights to all their photos taken at her shows.

Slightly harder to control are the rabid paparazzi photographers that have proliferated in Hollywood over the past decade. Popular targets have taken to disguising themselves, holding up signs (see Scarlett Johansson’s famous “I’m being harassed by the person taking this picture” sign), running from location to location, and sometimes even attacking the photographers who are following them (cf. Sean Penn and Woody Harrelson). But besides the immense danger the celebrities (and passersby, on foot and in vehicles) face in being mobbed, these off-duty stars also appear to be fighting what Sontag refers to as the democratization of their experiences.

“A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it — by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir,” she wrote. In short, part of what these stars may be objecting to is their day-to-day experiences being nullified by the paps that are falling all over themselves to snap them for our viewing pleasure.

“Why would I want anything that’s private to become entertainment for other people?” the infamously camera-shy Kristen Stewart seemed to ask for all celebrities in that 2010 interview with Elle UK. At the height of her Twilight fame, she was so used to her experiences being captured by journalists and photographers both that during the interview she hesitated before removing an iPod from her car’s glove compartment to show the journalist her music. “You want to be excited about something, normal people can be excited about their lives, and I am too, but it’s such a different thing,” she explained of her hesitation. “It comes out as entertainment for other people and that makes me want to throw up.”

Explaining her moodiness around paparazzi, Stewart contended that the public is not often privy to what happens before the pictures are taken. “What you don’t see are the cameras shoved in my face and the bizarre intrusive questions being asked, or the people falling over themselves, screaming and taunting to get a reaction,” she told Elle. “All you see is an actor or a celebrity lit up by a flash. It’s so… The photos are so… I feel like I’m looking at someone being raped.”

In her book, Sontag anticipated this type of comparison, stressing that photography requires distance while attacking someone sexually requires proximity. “The camera doesn’t rape, or even possess, though it may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit, and, at the farthest reach of metaphor, assassinate — all activities that, unlike the sexual push and shove, can be conducted from a distance, and with some detachment,” she wrote. Though the use of “push and shove” does conjure images of photographers clamoring to snap Stewart, the sexual aspect of the action is missing.

In the same interview, Stewart did, however, seem to be in tune with Sontag. “Your little persona is made up of all the places that people have seen you and what has been said about you, and usually the places that I am are so overwhelming in the moment and fleeting for me — like one second where I’ve said something stupid, that’s me, forever.” The words conjure up Sontag’s suggestion that “the force” of a photo is such that it allows viewers (including Twilight fans) to scrutinize “instants which the normal flow of time immediately replaces.” So, one image of Stewart grimacing at a crowd of paps, or a moment in which she says the word “rape,” reverberates across the universe and single-handedly becomes her undoing.

Though the camera doesn’t “rape,” it does “violate” its subjects, but according to Sontag, it’s only a figurative violation “by having knowledge of them they can never have.” Stewart herself cannot be possessed but as the subject of a photograph, an object that can be physically held, she is “symbolically possessed.”

This so-called symbolic possession becomes all the more realistic when you consider the way photography works, which Sontag explained as “never less than the registering of an emanation (light waves reflected by objects) — a material vestige of its subject.” Because of this, images can “usurp reality” since it is essentially “a trace, something directly stenciled off the real.” Sontag concluded by stating that the photograph being an extension of the subject captured, the image becomes a kind of means of acquiring the subject.

The statement gives a literal bent to Sean Penn’s comment in Playboy in November 1991 in which he described himself and Madonna as “public property.” It also makes Keira Knightley’s 2007 Crocodile Dundee-style, quasi-spiritual fear of being photographed appear slightly less ridiculous. “I’m not comfortable having to be myself or being photographed as myself,” she said. “Australian Aborigines say that with every photo that is taken, a piece of your soul goes with it. And there are some days when I kind of believe that.”

But Sontag’s book rebuts the idea that photography has the power to capture a piece of one’s real soul. “It is not reality that photographs make immediately accessible, but images,” she wrote. What’s confusing to celebrities (and much of the rest of the world) is that our era confounds reality with photographs. “Instead of just recording reality, photographs have become the norm for the way things appear to us, thereby changing the very idea of reality, and of realism,” Sontag claimed, adding that the “true modern primitivism” is not to consider the image real, but to consider reality an image that can only be realized through photographs.

Unfortunately, the only way to combat this primitive behavior, Sontag argues, is to see the photograph for what it really is, not a real instance of power, but merely a weak expression of it — as it is a weak expression of the real Depp and the real Stewart, and as such is no real replacement for the stars themselves or their bodies. “The knowledge gained through still photographs will always be some kind of sentimentalism, whether cynical or humanist,” Sontag explained. “It will be knowledge at bargain prices — a semblance of knowledge, a semblance of wisdom; as the act of taking pictures is a semblance of appropriation, a semblance of rape.”

Soraya Roberts is an entertainment writer and editor. She writes about films on her blog, Incinerater. She is also on Twitter, much to her dismay.

Photo of Stewart by Joe Seer, via Shutterstock.