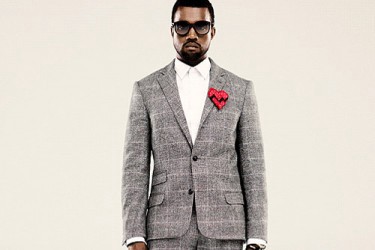

Kanye's '808s': How A Machine Brought Heartbreak To Hip Hop

by Emma Carmichael

Part of a series on collaborations that we now take for granted but initially made little sense.

Hip hop’s lyrical narrative often gets unfairly abbreviated to being about nothing more than posturing and persona, a never-ending series of mostly meaningless boasts about how nice my rhymes sound, and so on. That’s been a component of the story for a long time — recall Sugar Hill Gang’s proud pronouncement, in 1979, that “I got a color TV, so I can see/the Knicks play basketball” — but hip hop verses are also a place for confessions, specifically for those of black men. There’s a reason, for example, that Scarface once wrote a song in the form of a diary entry, or that The Notorious B.I.G. recorded a song for his suicide at age 24, or that Jay-Z wrote an entire hit song about not crying, and that each of them felt comfortable doing so on 16 bars.

The break beat is, and always has been, a haven for hyper-masculine confessionals that might otherwise go unspoken.

But Kanye West, long as the public has known him, has never needed the break beat to say what he wants to say. He’s not like Nas, who often sounds shy and characterless in interviews despite being a hell of a storyteller in his rhymes, and he’s not like Eminem, who always depended on his alter ego to share his darkest thoughts. His problem — especially outside of the recording booth — has always been the opposite: Kanye has always struggled to withhold (or at least to measure) his confessions.

His fourth studio album, 808s & Heartbreak, is the best musical and lyrical manifestation of Kanye’s need to say everything all at once. He released it in November 2008, after three hit albums that effectively branded a Kanye style of hip hop — and yet 808s wasn’t really a hip hop album. On it, Kanye doesn’t say anything we were accustomed to hearing on any hip hop track, and he doesn’t really sound like Kanye. He sounds like a cyborg. The album is a close partnership with machine (he used the vintage Roland TR-808 drum machine for his beats) and with a kind of artistic dishonesty (he used the modern Auto-Tune device to adjust his subpar singing voice in nearly every track on the album). At the time of its release, the final result was rather startling. Kanye had a style, and the 808 and the Auto-Tune just didn’t jibe with it. And yet the collaboration with those devices allowed him to sing real, unfiltered heartbreak — something that he hadn’t yet done in his career, and something that hip hop as a whole had never really dealt with before.

On 808s, Kanye doesn’t tell stories, and he doesn’t confess anything in any of the ways we’ve come to expect. There are none of the quintessential Yeezy lines, simultaneously self-critiques and boasts stitched into the songs’ stories: “Well all self conscious,” he rapped on “All Falls Down,” off of his debut album College Dropout, “I’m just the first to admit it.” But on 808s, if there are insecurities to be named, Kanye only seems to be admitting them to himself.

808s is not exactly subtle about its intent. The year before its release, as we all must be aware by now, had been rough for Kanye. His mother, Donda West, died of complications related to cosmetic surgery in November 2007, and a few months later he and his fiancé broke up. 808s & Heartbreak is, well, his heartbreak album, and that’s a hip hop subgenre that didn’t really exist at the time. On these songs, Kanye sounds hopelessly and intentionally lost. Unlike Jay-Z’s “Song Cry,” there is no masquerade at play: The only way Kanye is able to communicate his sadness is to state it, clearly and unapologetically and over and over again until the listener becomes quite sure that human sorrow has never sounded so processed before. It certainly hadn’t been sifted through a voice filter and laid out over sparse, electro-pop beats quite like this, at least in hip hop.

That was one of many perceived problems with the use of the 808 on the album. Kanye’s production had been celebrated because he’d created his own sound and perfected it until it became familiar, even the norm. On 808s, that sound shifted so dramatically and so forcefully, it sounded unnatural. The 808 took the place of the Kanye soul sample (there are just four samples on the entire album), and it did so prematurely. Kanye’s emotional burden is expressed in every layer he piled onto “Love Lockdown” — from the pulsing, opening beat to the jumpy piano line and his strained singing. The singing, it must be said, is just never very good on 808s. Throughout the album, Kanye is crying to himself and shouting at us at the same time.

Beautiful as the album sounds (and that’s a fact that’s been documented extensively enough), it is wholly exhausting to listen to. There’s never a mention of his Louis Vuitton shoes or his Maybach to relieve us from the heartbreak. The songs have names like “Coldest Winter,” “Welcome To Heartbreak,” and “Bad News.” Kanye says things like, “Chased the good life my whole life long/Look back on my life and my life gone” and “Let me know/Do I still got time to grow?”

Judging by the album’s reception, most people did not want to give Kanye West time to grow. A lot of people hated 808s and a lot of other people tolerated 808s (I loved it). The collaboration here, between man and machine, made for sparse, electro-style instrumentals that often stretched on — rather indulgently — for two or three full minutes after the final verse. Coming from a normally meticulous producer who was known to thrive on bombast, this just sounded unfinished, even boring. The immediate reaction to the album might have been similar to the one in Newport, Rhode Island in 1965, when Bob Dylan went electric at the Folk Festival. We don’t like drastic changes from the artists we’ve come to depend on for a certain kind of musical narrative, even if those artists happen to be going through drastic changes themselves.

Hip hop, especially, hadn’t really endured or welcomed creative leaps like 808s. There have been shifts to the music’s sound, of course: groups like A Tribe Called Quest brought jazz to the mix in the early nineties, and back in ’86, Run DMC and Aerosmith made the “Walk This Way” remix, which was one of the first merges between rap and rock and a total commercial success. Kanye has even credited himself for reintroducing soul sampling to hip hop in his early years as a producer. But all of these leaps sounded in keeping, in some way, with the music we’d come to know and love.

Kanye’s revision on 808s is different: it isn’t so much the shift in the sound that bothers listeners as it is the shift in the narrative. These lyrics don’t align, in any simple way, with the proud bombast of “Jesus Walks” or “Touch The Sky.” These are songs about a vulnerable black man who is trying excruciatingly hard to let us know how sad he feels, and these lyrics are not rapped. Within a culture that flaunts and rewards a rather established expression of masculinity, there is an inherent risk in that effort. Hip hop has heard heartbreak before, just not in this context.

With someone with as famous an ego as Kanye West, it’s disconcerting to see him so unguarded. You have to go back in time a bit to see that. It’s worth revisiting 2004, when the rapper Mos Def introduced Kanye to a studio crowd as “the future of hip hop” for the third season of the HBO show Def Poetry. College Dropout was out by the time it aired, but at the taping — and you can really tell by watching his later appearances on the show — nobody really knew who he was. Onstage, Kanye recited lyrics from the first and second verses of the song “All Falls Down,” only here, the form was a spoken word piece named “Self Conscious.” In it, he looks proud and humbled to be there; his clothing has nothing in common with the couture he wears today.

I’ve learned, since I discovered it a few years back, that I can watch this clip many times and never get tired of it. Part of the wonder is merely in observing someone who’s earned the carefully rationed “global superstar” title when he was a relative unknown. It was only shot about seven years ago, after all. But the real draw is that it’s a total recontextualization of a song to which I now know every single word. There’s no beat, of course, and no effect to his voice, either, save for Kanye’s exaggerated nervousness at the beginning. He takes more time to recite his words, pausing for emphasis or relief, and at one point — the 1:50 mark in the clip — he cuts his own rhythm with a faint aside. No one in the audience can interrupt, because no one knows what he will say next.

A few years ago, I sat in a living room next to a very drunk young man who was, along with many of the other young drunk people in the room, shouting the lyrics to “All Falls Down.” When he reached the middle of the third verse, he yelled out the line, “Drug dealer buy Jordans, crack head buy crack/And a white man get paid off of all of that,” and then he turned to me and said, laughing self-consciously, “I always feel so bad when I rap that part.”

In his Def Poetry performance, Kanye ended on the line that always made that particular white person feel very bad. He smiled out at the crowd in a kind of bashful pleasure, letting them hear what he’d said for a moment, and then left the stage. But on the radio version of “All Falls Down,” the line is edited out, so that we only hear, “ — — — — — — — — , crack head buy crack/And a — — man get paid off of all of that.”

808s has a lot in common with that Def Jam performance. It’s imperfect, totally raw and an absolute departure from what we think we know about an artist. The album was not great, but it was daring: It took hip hop’s confessional, twisted it into something overwrought and unrecognizable, and left it on the table to see what would happen next. Like the Maybach in the “Otis” video, he mangled a form to which he’d made us accustomed.

I don’t know if The Black Keys’ Blakroc project would exist — or if Jay-Z and Beyoncé would have gone to see Grizzly Bear together, or if Drake (or Kid Cudi, or The Weeknd, for that matter) would still be singing about millennial angst over electro beats, or if “Runaway” and “Devil In A Red Dress” on My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy would each have two-minute codas — if Kanye West hadn’t made an album that everybody seemed to hate, with a machine nobody cared to hear. 808s was a leap, but it made those other progressions sound more natural.

Those are silly speculations, though, because hip hop has always taken in music and samples and voices only to then spit them back up. It’s a constantly evolving music; it could, after all, even sustain the 808’s sound. The music’s lyrical narrative, for whatever reason, just hasn’t yielded as much experimentation. It’s hard enough to make exciting music; it’s even harder to say something new in 16 bars. When Kanye warped the sound of his voice over those stark, startling beats he made with his 808, he shifted the story by making a song cry, figuratively and literally and probably way too many times.

He found a way to admit to himself, “I’m sad and fucked up” and to still make us sing along with him and his machine.

Emma Carmichael works at Deadspin.