What Makes A Great Critic?

What Makes A Great Critic?

“The great artist is he who goes a step beyond the demand, and, by supplying works of a higher beauty and a higher interest than have yet been perceived, succeeds, after a brief struggle with its strangeness, in adding this fresh extension of sense to the heritage of the race.” — George Bernard Shaw, The Sanity of Art

I saw Pauline Kael speak once, “in conversation” with Jean-Luc Godard, many years ago at Berkeley. The place was mobbed and the event was a mess, with the so-called conversation quickly devolving into a shouting match (about Technicolor film stock, as I recall). But it was so great watching Kael yell at Godard, who was such a god around Berkeley at that time. Pleasurably shocking, in much the same way her movie reviews are. “Perversity!” she kept howling. I still yell that sometimes just for fun, in her memory.

I am crazy about Pauline Kael, just like everyone else is. She was a great artist, and a great benefactor of American culture, in exactly the way that Shaw describes above; she provided our age with the means to break free of hidebound ideas about the “correct” exercise of a serious mind. Where the default position in popular criticism before Kael had been merely censorious, she created a new and higher standard, one of real discernment. Plus her writing is exhilarating all by itself; irrepressible and fiercely independent, a flaming sword of justice. And this blade was always wielded absolutely on behalf of the reader, and nobody else. “Saphead objectivity” was her enemy, she once said.

In the foreword to 5001 Nights at the Movies, an indispensable collection of Kael’s capsule reviews for The New Yorker, she describes the book with characteristic pizzazz. “I hope that it is a guide to the varieties of pleasures that are available at the movies — from the fun to be had at the juicier forms of trash to the overwhelming emotions that are called up by great work.”

It has ever fallen to critics and journalists to create new ways of looking at new things, to relate the message of art to audience. The artist (or the scientist, or the politician) is necessarily absorbed in his own craft. The critic’s concern by contrast is the audience, which includes himself. He’s the citizen, the moviegoer, the diner, the art lover. He fashions his own experiences into a kind of bridge to new places we might not otherwise have cared (or maybe even dared) to visit. He creates or extends the shared experience that is the real purpose of culture.

Or maybe the critic just says the expected thing, seeing the movie or reading the book from the establishment point of view, making no personal connection either with the work or with the reader. Nobody remembers or really engages with such writers at all, but they are “safe” for establishment purposes and they can be trusted to not get into any snafus with Warren Beatty (as Kael once did). George Bernard Shaw once described this timid, conformist mentality perfectly, pointing out that there is always a change-resistant establishment against which the undeceived and openminded critic must fight.

It is from men of established literary reputation that we learn that William Blake was mad, that Shelley was spoiled by living in a low set, that Robert Owen was a man who did not know the world, that Ruskin is incapable of comprehending political economy, that Zola is a mere blackguard, and that Ibsen is “a Zola with a wooden leg.” […] it was the musical culture of Europe that pronounced Wagner the inferior of Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer. […] it is the Royal Academy which places Mr. Marcus Stone — not to mention Mr. Hodgson — above Mr. Burne-Jones.

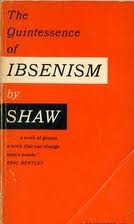

The Quintessence Of G.B. Shaw

In London in the spring of 1890, the Fabian Society, a gang of influential British socialists, found itself clean out of lecturers for its summer meetings. So they asked a bunch of their friends to kick in on a series of papers “under the general heading ‘Socialism in Contemporary Literature.’” Sydney Olivier got dibs on Zola, Hubert Bland took on a bunch of new Socialist novels, and Sergius Stepniak went for modern Russian fiction.

So it was that George Bernard Shaw agreed to “take Ibsen” and embarked on one of the best things he ever wrote, an essay eventually called The Quintessence of Ibsenism, published in book form in 1891. It is a political and feminist polemic, an early examination of poststructuralist questions, a brilliant illumination of the works of Ibsen — and an example of the heights of usefulness and enlightenment that literary criticism can attain.

It’s difficult to imagine the furor that Ibsen’s plays created in late-19th-century London. Polite society was absolutely not ready for a candid examination of its mistreatment of women, or the sordid results of driving sexual activity underground, or the generally festering mess to be found beneath the carpet of their virtuous conventionality. Does this sound familiar? It should, because the most cursory reading of The Quintessence of Ibsenism reveals an exact correlation between the pious hypocrisies of Victorian society and those of our own day.

The debut of Ibsen’s plays on the English stage resulted, on the one hand, in wild cheers for Ibsen’s moral leadership from an intelligentsia starving for the truth and, on the other, in the hysterical caterwauling of conservatives suddenly confronted with the personal and societal cost of their lies. Ibsen was kind of their Todd Solondz on steroids.

To illustrate the contrast, Shaw in The Quintessence of Ibsenism quotes a selection of the newspaper caterwaulings on the subject of the play Ghosts:

An open drain; a loathsome sore unbandaged; a dirty act done publicly; a lazar-house with all its doors and windows open… Candid foulness… Offensive cynicism… Ibsen’s melancholy and malodorous world… Absolutely loathsome and fetid. Gross, almost putrid indecorum… Literary carrion… [etc.]

And all that is just from the Daily Telegraph (plus ça change!). There was so much more! Other conservative rags added: “Naked loathsomeness,” “Revoltingly suggestive and blasphemous,” “Repulsive and degrading,” etc., etc.

“Just a wicked nightmare,” squeaked The Gentlewoman, once the smelling salts had been applied and it came to.

So why all the fuss? Well, mainly, Shaw explains, because Ghosts depicts a woman who really shouldn’t have stayed with her drunken and debauched husband, nor struggled so mightily to shore up his rep as an upstanding citizen of the community; who is shown to have been wrong to conceal the paternity of the love-child he fathered on their maid, and wrong again to keep the truth about the maid’s daughter from their son (the girl being his half-sister), who has likewise grown up to be a drunkard and a rake. A woman, in short, whose eyes are opened to the true cost of all her “dutiful” deceits when her beloved son is revealed to be dying of the syphilis (then a prevalent, and commonly hidden, condition) that he inherited from his father.

Shaw’s point here — partly a political one, and partly a literary one — is that contemporary morality absolutely recoiled at the idea, the possibility even, of a woman’s noble self-sacrifice turning out all wrong. Hence, caterwauling: they just could not deal. But Shaw did far more than expose the hypocrisies at the heart of conservative Victorian morality: “the iniquity of the monstrous fabric of lies and false appearances.” He explained exactly how they work.

Shaw calls the Ghosts-hatin’ class of conventional Victorian moralists “idealists,” and then says that the real problem for an idealist is the fact that regular family life is totally not working for him. (Why it’s not working doesn’t matter: he or she is unhappily married, or gay, or never wanted children, whatever. The crux is: not working.) The idealist lacks the courage to face the fact that he is a “failure” at family life — an “irremediable failure,” since he can’t alter the standard-issue morality, yet feels he must adhere to it anyway. That’s why each idealist must convince himself that no matter what his own situation may be, “the family is a beautiful and holy natural institution. For the fox not only declares that the grapes he cannot get are sour: he also insists that the sloes he can get are sweet.” That is why these “moralists” are so threatened by such things as the plays of Ibsen, marriage equality, etc.: the possibility of real freedom threatens their internal house of cards mechanism.

Shaw then contrasts the idealist, who can’t really stand conventional morality but pretends that it’s great, first with the Philistine, who is perfectly okay with conventional morality, and then with the realist, the rare person who does not care two pins what anyone else thinks, and lives according to his own morality, not the standard-issue one. A realist has no need to lie to himself or anyone else; and a realist, according to Shaw, is what he and Ibsen are. Or two realists, I mean.

So comparable is the condition of Victorian England to that of the United States right now that Shaw’s argument provides a credible explanation even of the imperatives of the many (many) “anti-gay” GOP politicians who have subsequently been discovered to be gay themselves: they’re Idealists, and so is pretty much everybody in the Tea Party.

Shaw found worldwide fame as a playwright but, to my mind, criticism was his real gift. He’d started as a music critic in 1885, writing under the name “Corno di Bassetto” for the Pall Mall Gazette as the protégé of William Archer. Then he was an arts critic for a bunch of different papers and drama critic for the Saturday Review. He wrote criticism alongside the plays for years and years, until he became such a literary lion that he didn’t really need to anymore. He kept up his political writing, though, all the way through his long life.

He had two main gifts as a critic. First was the total absence of the pomposity that distinguished most of his contemporaries (there were a few exceptions, e.g. Beerbohm and Wilde). In stark contrast to the Victorian house style, and from very early in his career, Shaw’s prose was lustrously clean and spare. (And bristling with razors.) Second, he meant, urgently, earnestly, for the average reader to understand his exact meaning. He pitched his stuff to the public, not the intelligentsia. Even if Shaw did have a lot of things ass backwards, which, hoo boy (he was utterly taken in by Stalin later in his life, and he was violently opposed to smallpox vaccination, and the list by no means ends there), there is enormous value in his work even now, and you can still feel the passion and purpose in every syllable.

But the salient point is this. These Fabians used to polish their arguments in the lecture-halls, where the audience would grill them like so many ribeye steaks after they spoke. In the preface to the 1891 edition of The Quintessence of Ibsenism, Shaw wrote of his first reading of the original paper “at the St. James’s Restaurant on the 18th July, 1890”:

Having purposely couched it in the most provocative terms (of which traces may be found by the curious in its present state), I did not attach much importance to the somewhat lively debate that arose upon it; and I had laid it aside as a piéce d’occasion which had served its turn, when [three of Ibsen’s plays were debuted in London, starting] a frantic newspaper controversy, in which I could see no sign of any of the disputants having ever been forced by circumstances, as I had, to make up his mind definitely as to what Ibsen’s plays meant, and to defend his view face to face with some of the keenest debaters in London.

In writing The Quintessence of Ibsenism, Shaw was preparing not just to be read, but also to test his views before a live and quite possibly enraged audience (or commentariat, as we might now style such an assembly). This work contains material both for scholarship and the rough-and-tumble of debate. And it’s what we might make of our own journalism, only the audience now can come from anywhere in the world, not just Piccadilly, London W.1. and environs ca. 1890.

The Book Of My Enemy Is “Magisterial”

A habit has sprung up among arts critics online of writing what I’m going to call “recaps,” meaning the sort of review in which the reader is assumed to have already seen the movie or television show or read the book under discussion, in contrast to conventional reviews, which seek to explain something about the subject work and/or situate the work and/or its author in some broader context. Recaps are chatty, familiar, conjectural; conventional reviews are more formal, authoritative and scholarly.

At first blush, this development seems a direct result of the speed with which journalists can now put their views before the public, and the irresistible opportunity for real, immediate interaction between them and their readers. The casual, intimate, assumptive manner in which recaps are written implicitly invites readers to join in the commentary that generally follows such pieces, which is often high-spirited and very entertaining. The pleasures of the worldwide water cooler are in no way to be sneezed at. It’s very easy to imagine Shaw or Pauline Kael tearing up the comment threads (and impossible to imagine Dwight Macdonald doing so).

So far, though, it seems to have been taken as a given that we don’t want to trade away what some might consider the deeper satisfactions of formal, painstaking analytical criticism for the casual, quick-and-dirty recap or powwow.

Or do we? Given the furious rate at which professional reviewers are being sacked, maybe it’s time to ask exactly what it is we want from arts criticism.

Some longtime book reviewers were laid off recently from the Los Angeles Times, and the occasion was marked by the usual wailing and moaning about the sad state of Culture and Reading Today. (Seriously, at this point, how many reporters can the LAT even have left, and are the survivors having to mop their own floors and also do elevator maintenance? Anyway.) Susan Salter Reynolds, Richard Rayner and Sonja Bolle were among those given the heave-ho; Reynolds had been at the paper for over two decades. Tom Lutz of the recently launched Los Angeles Review of Books hired her and Rayner straightaway, and wrote a much-cited piece on August 6th regarding this move and the significance of the Times layoffs, among other things.

The layoffs in the newspaper and magazine world cause enormous harm to our friends and colleagues, but the tragedy for American culture as a whole is more profound. We are losing access to great swaths of knowledge and proficiency. Few people alive have read as many books as Reynolds, Rayner, and Bolle.

Whoa, there, though? Having read a lot of books is possibly the last qualification we need in a critic. It does not follow in the slightest that Critic A is better than Critic B because he has read 100 or 1000 more books than has Critic B. This is in no way to slight Reynolds, Rayner or Bolle, by the way. I mean only to point out that the most we can say is that some relevant preparation may add some interest to a critic’s work (and by all means, both Pauline Kael and George Bernard Shaw had deeply scholarly habits and were beyond prepared).

What we really need is a critic who has got something interesting to say. Who is writing something that we would like to read. Whose aliveness just comes out and grabs you by the throat and makes you think, or go pop-eyed with amazement, or throw your monitor across the room in a fit of rage. As a lover of good criticism, I am asking, or demanding (more like begging, really), that this passion and immediacy be the first quality that should recommend a critic to public notice.

What if the cozy and rarefied world of conventional reviewing is on its way out for a good reason, namely, that people aren’t the slightest bit interested in reading that kind of writing anymore? Not because it’s “serious” or “intellectual,” but on the contrary, because it ain’t. Maybe part of the problem is that we are no longer content to have the conventional book given a conventional reading by a conventional critic?

When was the last time you read a really scorching arts review in an ordinary newspaper? I don’t mean just vitriolic, I mean one that was thoroughly exciting because it cast an entirely new light on something. You like this, you don’t like that, who cares? Nobody really, not unless you say why. An unadorned “boo” is no better than an unadorned “yay.” It’s the why that creates the hotly beating heart of good criticism. Splashing the vitriol around is attractive to certain writers but the vitriol is like Angostura bitters, you can’t drink it on its own; it requires the gin of explanation and conjecture, the ice cubes of levity, and then you have a Pink Gin, which is an excellent cocktail? — never mind all that, what I mean is that the bald declaration that something is “terrible” (or “towering”) is the opposite of discerning, it’s cheap as can be.

And here is why: any critic should respect the reader enough to encourage him to make up his own mind, just as if that reader were standing right in front of him. The skilled critic will make no assumption regarding the tastes or habits of his reader. And it’s the assumption that we’re all “educated” “sensitive” people together that dampens modern literary criticism the most.

Review after review, it’s almost all “magisterial” this and “lyrical” that, with the odd hatchet-job thrown into the mix for flavor; the dull and hoary conventions of the form, the requirements of a large, slow-moving institution and the clubbiness of the publishing world all combine to produce deadened white-guy prose of exactly the kind the world needs less of, lockstep agreement of the “civilized” kind, strained tapioca for the so-called liberal elites.

I know these institutions are difficult to keep from calcifying, and I know they have a value that’s worth saving. But it’s nothing new to point out the conflicts of interest faced by the journalist or critic who has met his subject in a social setting. Francis Wheen’s whomping “The hunting of the snark,” published last week in the Financial Times, touched on this theme with respect to book reviewing. “DJ Taylor, who reviews about 50 books a year, believes that ‘the English novel is consistently let down by a deferential reviewing establishment with an engrained reluctance to condemn inferior work.’” Surely that has to be true everywhere there is an established publishing industry, maybe everywhere there is an “establishment.”

There are a lot of critics and reporters out there who consistently produce writing with fire, immediacy and humanity, I hasten to add, on- and offline. But one cannot at present look to establishment publications for the most exciting, deft or provocative criticism on offer. Maybe they could sell more papers, if they’d try to get some of that?

Seen from this perspective, perhaps the most valuable thing that the newly emerging recap form gives us is a little shot of that Shavian immediacy, a bit of the sizzling atmosphere of the St. James’s Restaurant of 1890. Someone to contend with, a space away from the tired, flabby, conventional critical apparatus. Contact with a writer with the freedom to go a little wild in his ideas, and who can effectively reach out to, and even engage with, a real audience. Maybe all that’s needed is a little more bulking-up of the critical musculature in order to achieve and maybe even surpass the Shavian heights. Only imagine where this can go, if we will only let it.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like A Gentleman, Think Like A Woman.