Murder, Suicide And Mayhem In Brooklyn Heights (Yes, Brooklyn Heights!)

Murder, Suicide And Mayhem In Brooklyn Heights (Yes, Brooklyn Heights!)

Very little happens in Brooklyn Heights. During Truman Capote’s years here, his friends would enquire, “But what do you do over there?” It was a fair question — and an eternal one. Mine wonder the same thing. One pleasure of America’s first suburb is that it is, to an extent unusual in an ever-churning city, impervious to change — economically, structurally, but also in a more fundamental sense: The question, Did anything happen in the Heights today? can almost always be answered with Not much. The news is blessedly mundane: Either a pet is missing or the street’s been sullied by a fallen tree or pothole.

If the Heights seems like a neighborhood out of time, that is to some extent by design. Its landmark status, bestowed by Mayor Wagner’s Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965, limited new structures to the height of a four-story row house and ensured the Heights would always look a bit like “Sesame Street,” whose creators lived in — and, legend has it, drew inspiration from — the neighborhood. Population growth has been flat to slightly negative for a decade; turnover on Montague Street is confined to a new bank and another new bank; and the hipness factor is, if anything, negative as well.

There are rumors that t’was not always thus. My neighbor, a lovely, rascally George Carlin doppelgänger, insists the Hotel St. George was ground zero for orgies in the ’70s. If you believe Bob Dylan, Montague was once home to “music in the cafés at night/And revolution in the air.” (We still have a cafe. It’s called Tazza and the coffee is okay.) But by the time young Barack Obama moved here in the early ’80s, any wild stories he might have heard about the place were outdated. It’s been a quiet place for a long time.

That’s not to say, however, that a cloud of violence and brutality never descended on the Heights. It has, albeit in a small way. No neighborhood is immune to a deadly drizzle every now and then, and mine has had its share, particularly in the early years before it was absorbed into the greater New York leviathan. While the Heights couldn’t be confused with the Five Points — “chippies” and their “maudlin songs” were the big problem of 1893, says The New York Times — it saw a respectable amount of murder, mayhem and even a prize fight. Here are some of the stories that rocked the dailies then.

A Shooting On Christmas Day

On December 25, 1877, Mr. Charles E. Johnson attempted to kill his wife Florence at his father-in-law’s 43 Monroe home. The incident, reported the Brooklyn Eagle, “has produced more excitement in society and police circles than any tragic affair which has occurred in some time.” Florence and the Manhattan-born Johnson, barely 20 years old and baby-faced, wed only a year earlier in a ceremony presided over by Reverend Henry Ward Beecher. The wedding, said The New York Times, “attracted much attention among the people of fashion in both cities by reason of the high social standing and wealth of the contracting parties.”

Charles and Florence had been married only a few months before he turned ill-tempered and verbally abusive. Nine months into the marriage Florence gave birth to a beautiful child. Life with Charles continued to be unendurable (he remained ceaselessly unpleasant), so she packed up and moved, child in tow, into her father’s home. Once apart from her husband, Florence, observed the Eagle, “regained her lovely spirits.” On Christmas Day, the poor woman (for reasons unknown) invited her father-in-law over to explain why she had left his son. Charles showed up in his stead, and shot his wife — as she held their baby — above the right breast with a five-chamber Smith & Wesson revolver. En route to the police station, Charles was apologetic. “I didn’t intend to shoot her,” he told the officer. “I merely wanted to frighten her.”

The shooting caught the neighborhood by surprise. From the Eagle: “[H]e would be the last one in the world who would reasonably be suspected of being capable of figuring as principal in the shooting business.”

Six months later, Charles, who had been charged with attempted murder, was declared insane on the basis of his wife’s testimony in which she disclosed that her husband had once before threatened her with a pistol. The doctors disagreed on whether he had epilepsy or dementia, but each believed Charles to be “thoroughly insane.”

Sibling Suicides

On February 5, 1893, Miss Sallie Coop of 144 Montague was found on the third floor of her home in what the Eagle described as “a state of semi-consciousness.” There was a pistol by her side; around her was the smell of chloroform; and her bed robes were covered in blood.

Sallie left no note, but it was said the marriage of her twin sister Elizabeth to George Perry Fisk — at which she was the maid of honor — “preyed upon her mind.” The ceremony had taken place a week before her death. At the reception, noted the Times, “Miss Sallie seemed to be one of the very happiest in the company.” Even so, Sallie was frequently melancholy and her periods of depression had gotten progressively worse.

Seven years later, Sallie’s brother Herman, suffering from financial losses and a failed love affair, shot himself in the head while standing on their father’s grave in Greenwood Cemetery.

He was buried near his sister in lot 12868, section 4.

A Hungry Child

How it was that Mamie Holland, 10, went from the Home for Destitute Children to a grave in Potter’s Field in the span of weeks was a matter of contention at her funeral on Monday, June 6, 1887.

The child’s deterioration was rapid: Three weeks prior, Mrs. C.F. Martin brought Mamie to her boarding house at 93 Pineapple on the condition that the girl would act as a nurse to Mrs. Donahue, a boarder. She became ill the first night. Mrs. Donahue endeavored to return Mamie to the Home, but was overruled by Mrs. Martin after the girl begged to stay.

Mamie’s health showed no improvement. Dr. W.H. Bates examined her and found that she was half-starved. Mamie told the doctor that the Home, where she had lived for five years, was to blame. “She told me several stories about the way she had been treated at the home, and if her stories were true the children there are certainly poorly fed.” Mrs. Martin told The New York Times that Mamie “hardly knew what meat was.” An autopsy confirmed the cause of death as rheumatism of the heart.

Stories of mistreatment of the Home’s charges were denied by Matron Battie, who produced several children to the Times for inspection. The reporter confirmed they did indeed appear healthy.

Taking Aim At The Landlady

Did James T. Walker intend to kill his landlady? Well, the landlady herself, a Mrs. Barbara A. Davidson of 14 Willow, said it was all a misunderstanding. The story, as told by the officer on the scene, Roundsman McCarty: Shortly after 7 p.m. on January 29, 1880, he was summoned by Mrs. Davidson’s nephew, who he had heard a gun fired in the boardinghouse. The roundsman entered the house, confronted Walker and found two pistols in his pocket. Walker, visibly drunk, was asked why he shot at Mrs. Davidson. “That’s my business,” he answered. “She has ruined me, and I will kill her yet.”

Walker’s non-denial was confirmed by Mrs. Davidson, who told Captain Crafts of the Second Precinct that Walker had indeed tried to kill her.

The next morning, Walker strode into court. According to a gimlet-eyed reporter for the Times, his blond mustache was “waxed and twisted in a way that bespoke a regard for his personal appearance amounting almost to foppishness.” The prisoner “did not seem to be much concerned by the predicament in which he found himself.” Mrs. Davidson, whom the paper tartly deemed “not specially attractive,” testified that Walker followed her into her room on the parlor floor, grabbed her shoulder, and said, “What does this mean?” as he fired two shots over her shoulder. As Mrs. Davidson hastily left the room she heard a third shot, which, she supposed, was Walker’s feigned attempt at suicide.

Judge Walsh: What would he do it for?

Mrs. Davidson: Oh, I don’t know; I suppose he was jealous.

Judge Walsh: Jealous — about what?

Mrs. Davidson: Oh, I couldn’t tell you, I’m sure.

Mrs. Davidson’s hesitation wasn’t surprising. She had not been honest with the police, neglecting to mention that she had of late attracted the attentions of a former boarder, a young commission merchant named Harry Ferris. Both parties were married to other people, so this was awkward. The police believed that, on the day in question, Ferris had visited Mrs. Davidson in order to pay the balance of his bill. Walker, they said, probably discovered the two together, assumed the worst and that is when the shooting started.

The Hoop-Skirt Fire

At a little past 4 on Friday, March 15, 1861, a fire broke out on the fifth floor of 106 Orange, home to the American Hoop-Skirt Company. Susan A. Wilson, daughter of the building’s janitor, and Ann B. Tranahor, a seamstress, were killed.

Engine Company No. 3 found Ann “nearly suffocated.” She was taken to City Hospital where, reported The New York Times, “[s]he vomited quite freely, and having received no other injury than that caused by inhaling smoke, strong hopes are entertained that she will recover.” Ann was visited in the hospital by her brother-in-law, Theodore Questoff, a Paymaster’s Clerk in the US Navy. She expected to die and a day or two later, she did.

Susan, who not only worked at 106 but lived in the basement, jumped from a window and fell approximately 60 feet to the concrete pavement. She was pronounced dead within five minutes of her discovery. The police surgeon claimed she had not broken a single bone.

In the weeks that followed, George Albrecht, the company foreman, was subject to an inquest. There was no evidence pointing to his guilt and a jury did not find him responsible. As quoted by the Times:

“That the deceased came to her death by precipitating herself from the rear window of the fifth-story of No. 106 Orange-street [sic] causing a fracture of the spinal column, and exonerating George Albrecht from all blame.” Signed, Duncan Richmond, Asher Williams, Wm. Little, Abner Terwelliger, Peter Walters, A.H. Campbell.

Three months later, 106 Orange was lit up again, this time with a fire on the fourth floor. It was, said the Times, “presumed that the fire was set by some malicious person.” There were neither fatalities nor injuries.

Boxing In The Living Room

On the night of March 2, 1887, Patrick Fitzgerald and James Larkins, notorious pugilists both, needed a place to break each other’s faces.

The first stop for the fighters, officials, reporters and a dozen paid spectators was the Pastime Clubhouse House in Manhattan at 66th Street on the East River. They expected it would be empty; it wasn’t. A trip to Long Island was proposed, but the idea so disgusted the spectators that most of them left. Then a butler, who happened to be a pal of Fitzgerald, suggested that they might head across the river. His employers lived in Brooklyn Heights and they were away. He reasoned that their dining room would be an excellent place to have the match; so long, as the Eagle put it the next day, spectators could “restrain their enthusiasm sufficiently to prevent the neighborhood from being alarmed.”

The crowd, reduced by then to the timekeepers, the seconds, reporters and the fighters, walked across the Brooklyn Bridge — the construction of which had been completed four years before. By the time they got to the Heights it was past midnight and the neighborhood was quiet as a crypt. The crowd entered the house and prepared the place for the fight: the furniture was removed and overcoats, dresses and “ladies wraps” were put on the floor to “deaden the noise.”

The fight began at 3:40 a.m. The terms:

• Five hundred-dollar purse, funded by “100 sporting men of New York, Jersey City and Brooklyn”

• Four-ounce gloves

• Fight to the finish

Larkins was 5’7″ and weighed 120 pounds. Fitzgerald was 5’4″ and 117. Both men were considered to be in excellent condition.

The first two rounds were deemed even, each man “fighting fiercely and taking punishment gamely.” In the third round both were knocked down with Larkins getting the edge. He was knocked into the fireplace in the fourth round but made Fitzgerald bleed in the fifth. Fitzgerald broke a small bone in his right arm but kept fighting. As the 12th round commenced a non-fight-related noise was heard. The butler, who one suspects may have at that point had a guilty conscience, left to investigate.

It was The Boss. “Thomas,” he was heard yelling, “is that a dance party you are giving?” The butler attempted to explain what was going on, but the master of the house tossed him aside and entered the dining room. For what happened next it’s worth quoting the Eagle scribbler in full:

He saw two men, whose bodies were bare to the waist, banging each other all over his dining room with comparatively bare hands. Their faces were puffed and bleeding, and they seemed tired, but their ferocity and determination was far from being exhausted. A baker’s dozen of spectators cheered them on.

The homeowner blanched and threatened to call the police. It was only then the crowd realized he had returned home. A few suggested tying him up, but that proved unnecessary. Once he agreed to “a vow of secrecy,” the crowd agreed to leave. It was decided that the fight was a draw, so Larkins and Fitzgerald would split the purse.

Elon Green writes supply-sider agitprop for ThinkProgress and Alternet.

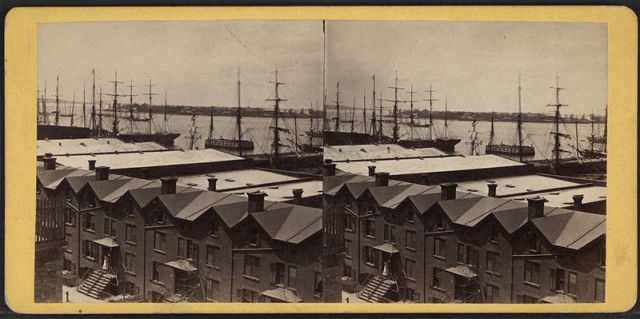

Photo from the Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views, New York Public Library.