Weekend At Kermie's: The Muppets' Strange Life After Death

by Elizabeth Stevens

Muppet trailers are making the rounds of the Internet these days. There are a few spoofs: rom-com, superhero and heist parodies, and then the official trailer for the new movie, which promises “muppet domination” this Thanksgiving. Presumably, this domination will mean a return to the box-office and critical success of days of old. And I have to admit: it’s exciting. Anyone who remembers the Muppets remembers them fondly. If there’s an anti-Muppet faction out there, they’ve kept quiet.

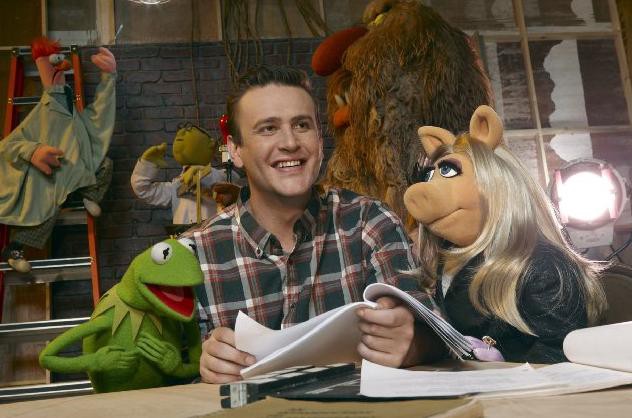

Jason Segel, the creator of the new movie, clearly shares this sense of nostalgia:

I’ve just grown a little disappointed with…all these weird concept movies. I just want to go take it back to the early 80′s, when it was about the Muppets trying to put on a show. That’s what I’m trying to bring back…

But despite great intentions, Segel’s movie will not be — can not be — like the old films. The post-Henson (that is, post-1990) films struggled to find the right tone. Even the best of them, The Muppet Christmas Carol, is too sweet and not salty enough. Muppets from Space swings erratically from callous to cloying. Segel is a writer-performer-producer with a kind, hilarious vision, not unlike Henson himself. His writerly debut, the 2008 movie Forgetting Sarah Marshall, features a break-up with full frontal nudity and a scene of sobbing over an ex’s Tupperware; it’s pitch-perfect. But even with all the right ingredients, the new Muppet movie has too much working against it. The first hurdle is a fuzzy, green hand puppet.

That’s Not My Frog

From 1955 to 1990, Kermit the Frog was voiced and performed by Jim Henson. After that, Steve Whitmire, known for his smart-mouthed Rizzo the Rat, took over. Whitmire’s Kermit sounded a lot like Henson’s, but his voice was a little thinner, and his singing more rhythmic and less melodic.

Let me preface my next statement by saying that I know it will seem ridiculous to the casual reader, inflammatory to a good many fans, and downright specious to the expert of rhetoric, but for me watching Steve Whitmire’s Kermit is akin to watching someone imitate a mythic and longed-for mother — my mother — wearing a my-mother costume in a my-mother dance routine. This person’s heart is in the right place, which only makes it worse. “You should be happy,” the person pleads with me, “Look, Biddy! Your mother is not gone! She is still here.” Now, no one would ever do that. No one in her right mind would think it would work. A child knows his mother’s voice like he knows whether it’s water or air he’s breathing. One chokes you and one gives you life. Strangely, I feel the same about Kermit. Whitmire is an amazing performer — especially as the lovable dog Sprocket on “Fraggle Rock” — but, when he’s on screen as Kermit, I can feel my body reject it on a cellular level.

In the 2000s, the Muppets turned up a lot on TV; they do game shows, reality, infotainment, late night, usually promoting a DVD release or movie with a few gags. In 2007, Kermit showed up on “America’s Got Talent,” sharing a cheesy duet of James Taylor’s “You’ve Got a Friend” with a contestant. What was strange about this cameo (besides that it wasn’t at all funny) is that Disney didn’t use Whitmire for it. The frog was puppeteered by another guy than the other guy. Kermit had been Weekend-at-Bernie-ed. And as I watched, I wondered, on behalf of all Muppet fans, how did we get here?

When Giants Meet

At the end of his life, Jim Henson was in talks with Disney to sell the Muppets. As the talks progressed, the two entities made a TV special together called The Muppets at Walt Disney World. This hour-long romp gives us a sense of what the merger might have been; in it, the gang sneak into Disney World and turn everything on its head. Gonzo and Camilla pretty much do it in a laundry room on top of the theme-park employees’ uniforms. Charles Grodin, playing a security guard, tells Rizzo that rodents aren’t allowed in the park. In his New York nasal, Rizzo shoots back, “Oh yeah, does your boss Mickey know that?” Fozzie works the enchanted kingdom into his act: “How soon can you get film developed around here, he says, and I say to him, some day your prints will come. Get it? Prints? Film?” In another scene Animal chases a shrieking Snow White down Main Street USA. Who but the Muppets could get away with calling Mickey a rodent? Who else could turn Prince Charming into a corny joke?

Kermit’s weirdos (as they often called themselves) wreak havoc across the Disney universe, which was, around that time, a rather staid, stodgy simulacrum of fun. The contrast between the two styles is striking from the first frame. In the opening, Michael Eisner makes a CEO’s attempt at palling around with Fozzie and his mother Mrs. Bear that shades from wooden to weirdly ominous. “They’re here!” he says, sounding more like he’s introducing Freddy or Jason than a crew of puppets.

Watching the special, it’s easy to see how the Muppets could have brought much-needed personality to the Disney franchise if only Disney had valued the artistic process that created the multimillion-dollar product. But sadly, this isn’t what happened. After a brief sale of the Muppets to a German company in the early 2000s and a buy-back, the Henson heirs finally completed what Jim Henson began, and in 2004 they sold the Muppets to Disney. Now Kermit does “America’s Got Talent,” and his act is staid, stodgy and disappointingly safe.

The Hensons’ deal was not the same as Pixar’s. Pixar, another independent company bought by Disney, got $7.4 billion, one hundred times more than what was rumored to be on the table for the Muppets. More importantly, Pixar got their payment in Disney stock, which means they are still around to exercise quality control. And where John Lasseter, Steve Jobs and Ed Catmull were able to preserve the management structure at Pixar, in fact expanding its power by making its top execs board members at Disney Animation Studios, the Henson Holding Company sold Disney the Muppets’ likenesses. This transaction is often described in the press as Disney Company having acquired the Muppet properties, the characters and all related copyrights and trademarks. Michael Eisner tried to add to this deal, saying, “We are honored that the Henson family has agreed to pass on to us the stewardship of these cherished assets.” Be that as it may, since 2006, when Disney bought Pixar, Pixar has won the animated feature category at the Oscars every year — and last year Toy Story 3 not only won best animated feature, it was nominated for best picture, too. So far, not a single post-Henson Muppets movie has been nominated in any category.

It’s worth remembering that the origins of Disney and the Muppets are very similar — both began as the vision of single artist who was able to delight and unite a large audience. Henson himself was inspired by Walt Disney’s artistry. When Muppets composer Paul Williams wrote “Rainbow Connection” for The Muppet Movie, he was attempting to capture some of the magic of Pinocchio’s “When You Wish upon a Star.” Disney’s Robin Hood was and is as good as any Toy Story movie today. But since the greed-is-good ’80s, Disney has gone to the execs. And if there’s one thing execs like, it’s not sinking money into artistic risks; it’s licensing cherished assets for big cash. Disney’s Pinocchio and Henson’s The Christmas Toy both featured toys that came to life. Yet, as its business model, Disney does the reverse — it turns life into toy.

Copyright Is A Good But Tricky Thing

Strangely, in the United States, copyright confers a much longer term of exclusivity than a patent. A patent — for say, the Flowbee or the Shake Weight — is good for 20 years after you file it. But copyright — for writing, recording, image or film — lasts much longer, extending across the author’s life to 70 years after his or her death. (Before the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, the terms were life of the author plus 50 years.)

In theory, copyright is a good thing, a necessary protection for artists that allows them to reap the rewards of their hard work. But 70 years after an author’s death is too long a period. It holds the work in an artificial suspension, the property of stewards who may, as the years go by, have less and less of a relationship with the original impulse that animated the art.

The Copyright Term Extension Act is sometimes called “The Mickey Mouse Protection Act” because it stayed the mouse’s impending deliverance into the public domain until 2036. But whom exactly does Mickey need protection from? The public domain — isn’t that us? What does Congress think we’re going to do to him?

Disney’s deal with the Hensons seems to rely on intellectual property law, but copyright concepts inadequately protect Henson’s work because it’s so difficult to reduce a Muppet character to a list of features. Ideas, it should be noted, cannot be copyrighted, only “original expressions” of ideas. You cannot copyright, for example, the idea of an all-raisin band, but you can copyright a band of raisins called “The California Raisins” who have specific features, such as half-closed eyelids, two-tone dress shoes and Mickey Mouse gloves, provided there isn’t one on the market already. Copyright law is particularly easy to follow when it comes to writing and recordings, because they can be copied identically. Scripts, images, blueprints — all of these can be easily duplicated.

But while the visual design of Muppets may be duplicable, the characters are more than static designs. To my way of thinking, a Muppet is above all made of two things: the voice and the dance of the Muppeteer. It’s very hard to copyright a dance, because it’s a form not easily reduced to notation or video. It’s tricky. A voice (and not the recording of the voice) is even more ephemeral. Both voice and dance need to feel alive in order to make us feel something; they can’t be repetitions of a script or design. In a sense, they need to be constantly evolving. What they are, really, is an emanation from the performer. Gonzo would not be Gonzo without Dave Goelz’s lucid absurdism. Piggy would not be Piggy without Frank Oz’s genius sense of humor and radical honesty. Robin would not be Robin without Jerry Nelson’s amazingly melodic voice. Red Fraggle would not be Red Fraggle without Karen Prell’s boldly audacious joy. In order to create personalities we love, Muppeteers tap into something that’s within them, putting all of their body into one hand and one voice. It’s admittedly hard to quantify or qualify — I struggle with gooey words like essence and soul — but maybe I don’t even need them. Perhaps it’s sufficient to say: it is the spontaneous voice and the unrepeatable pantomime that carry everything.

A Celebration Of Human Limitation

In many ways, Muppets are crude. Theirs is a makeshift aesthetic. Compared to the beauty of Disney’s cartoonscapes or the depth of visual information contained in Pixar’s photorealistic backdrops, their scenes look homely as craft projects. Henson knew that the feeling of realism does not require verisimilitude or loveliness, but rather the movement of life — constant movement of body and voice. You can close your eyes and watch episode after episode of “Fraggle Rock” without ever becoming confused about what’s going on, because the voices of the characters pull you through. Likewise, you can watch a Muppets dance routine without sound and be just as delighted by the countless little touches that animate it — a syncopated head bob here, a hammy grin there. What matters in the Muppet universe isn’t perfection, but expression. Dancing across the screen, they embody the philosophy that it is not what you look like that matters, but what you do.

The most elaborate visual productions created by Henson and his team were Emmet Otter’s Jug Band Christmas and The Dark Crystal. The first film had a 50-foot river snaking around cattail-spiked bends through little towns, and an audience of naturalistic animals dressed up in hand-sewn bustles and bonnets. The Dark Crystal introduced the viewer to a world with its own unique flora and fauna, with Amerindian sand paintings, giant crustaceans and a gargantuan castle that eventually crumbles to the ground. It took five years to make and is, in my opinion, one of the greatest artistic masterpieces of the twentieth century. When I say that the Muppets’ art direction is makeshift, I don’t mean that it’s shoddy. But it celebrates human limitation. As we watch one of these movies, we never lose our awareness that these scenes were made by men and women. Craftmanship, the game of how good any one artist can be, is presented — not hidden — and as such it can inspire others. For all its opulence, Disney’s Beauty and the Beast does not tell me anything about what it’s like to be a human being.

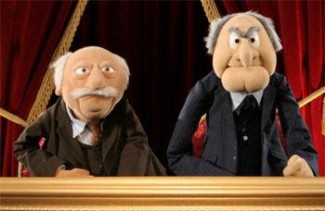

The Laws Of The Muppet Universe

To this day, no one (outside of the movie’s own crew) knows how the Muppets rode bicycles in The Great Muppet Caper, the classic Henson movie from 1981. In that scene, Kermit stands up on one frog-leg on the seat of his bicycle to impress Miss Piggy, and then the whole gang joins them on their bikes, doing circles and figure eights, singing “Couldn’t We Ride?” It’s a wonderful piece of filmmaking, and still a complete delight to watch because the effect relied on the ingenuity and bravado of the puppeteers and crew, not CGI wizardry. Contrast the joy and ebullience of this scene to the elegant chiaroscuro slickness of the post-Henson Muppet Christmas Carol in which we see old fogies Statler and Waldorf, as the Marley brothers, floating in mid air. No viewer is impressed; no one really thinks about it at all. And that’s because when a then 29-year-old Brian Henson directed that film, he threw the rules out the window. Statler and Waldorf “float” because Goelz and Nelson, the men working the old guys, were standing behind them during filming and then were removed in post production. It’s an elegant fix — a cutting of the Gordian knot — but it is a complete break with an aesthetic 35 years in the making.

Rules get a bad rap, but the rules are what define the Muppets. The rules were the reason for so many scenes where you don’t see legs or feet. Kermit’s tap-dancing (seen only from the waist up) is funny because of the rules. Kermit, so proud of his footwork, almost makes us forget that he doesn’t actually have feet to work. It was the rules that gave us those wonderful conclusion scenes — everyone, all the Muppets you can imagine, together in one room, singing the same song, in rows, arranged so that everyone’s faces can be seen. As viewers, we know on some fundamental level that what we are seeing is not CGI, but a room full of exhausted, exhilarated professionals with their arms stuck inside of puppets. Jim Henson’s direction acknowledged the limitations of space, time and gravity. If a Muppet’s feet were visible, those feet belonged to a marionette. If a Muppet flies, it is because an unseen hand has flung him across a room. Which isn’t to say that Henson didn’t use television tricks — he did — but he always did so to push the art, not to cut costs. When he used the then-cutting-edge green screen in Labyrinth, his performers used the new medium to invent quixotic new ways for the Fire Creatures to dance. You could say that, in a way, the strings were always a part of the act.

A Strange Way To Make A Buck

Most biographies of Jim Henson are full-on lard. Nowhere in them does anyone say an ill word about the man, and we, as readers, know that that is a necessarily incomplete picture. But if we examine Henson’s work in earnest, we can find an inextricable quality running through it, a constant that we can rightly call character. This sense of character is what any fan intuitively recognizes as part of the Muppets’ “assets,” yet it didn’t follow them past 1990. And how could it?

Now, Jim Henson was always a willing participant in the marketplace, and as Malcolm Gladwell points out in The Tipping Point, Grover began as an IBM spokesman. Which is certainly true, and Rowlf the Dog did films for corporate meetings. He sold typewriters door-to-door in Henson’s early “meeting films,” a peculiar subgenre of the commercial designed for business-to-business sales pitches. It’s all there on YouTube. Gladwell argues that “Sesame Street” was an extension of these commercials, but he’s got it the wrong way around. It’s the commercials that embody the ethos of “Sesame Street.” I laughed — forcefully, involuntarily and out loud — at one reel in which a character was shot at point blank because he said he didn’t use the product. Later, I couldn’t even remember the product’s name. These works are not just making a buck for the buck’s sake. There’s a willfulness in them, a refusal to ever place the market’s demands above one’s own values. We see it again in The Muppet Movie when Kermit refuses to do a commercial for Doc Hopper’s frog legs. Like Kermit, Henson was unwilling to compromise his vision, and as best as I can tell, he made the buck to pay for making more Muppet shows.

In a 1979 interview with Morley Safer for “60 Minutes,” Henson describes his job this way: “Kermit finds himself trying to hold together all these crazy people, and there’s something not unlike what I do.” Why would anyone choose a job like this? With a hypothesis clearly in mind, Safer asks him, hardball-style, how much the “Muppet Empire” is worth, “scores of millions, millions?” Henson, visibly uncomfortable, defers to Kermit, seated beside him, who riffs nervously on the cost of green fleece and ping pong balls. Under Safer’s stare, Henson eventually admits his business is worth millions, “probably.” As Henson awaits the next question, his eyes appear dewy, perhaps hurt or angered, at the insinuation that money is his real game. This is, after all, a man who stayed up all night painting numbers for “Sesame Street”’s Number Songs.

It might seem like hyperbole or some kind of lard in our cynical era. Netflix categorizes “Fraggle Rock” as both “feel-good” and “family-friendly,” and descriptions like these can make the work seem unserious. But it’s no small feat to balance art and commerce. So few of us actually attempt that “Rainbow Connection” and fewer still succeed. It’s not naive to admit that what we like about the Muppets is this willful spirit — that art is something to do for its own sake.

A Kermitless Muppets?

Indulge me for a moment in a game of “what if.” What if, in 1990, instead of recasting Kermit — something that had been done to Mickey and Bugs Bunny before him — the Muppets had continued on Kermit-less, as “The Simpsons” did after Phil Hartman died. Recall Susan’s words on “Seasame Street” about Mr. Hooper in 1982: “Big Bird, when people die, they don’t come back.” Let’s say Robin showed up saying his uncle Kermit had passed away? Or, if that was too dark for Disney, what if Kermit had left show business to go off to start a family with Piggy? Someone else could lead the gang of weirdos. If a bigger part was in the cards for Whitmire, how about as Kermit’s long-lost brother? How about another nephew? Jerry Nelson’s assertive Gobo Fraggle led a Muppet cast that functioned perfectly well without major roles for Henson or Frank Oz.

It would’ve made more artistic sense than what happened. Instead of an organic personnel shift, Whitmire became Kermit, which wasn’t only a disservice to that character, but also a real disservice to Whitmire. There was no place for him to take the role. If he strays too far from Henson, embodying Kermit with the parts of his personality that weren’t in Henson, nostalgic fans will be disappointed. He can only attempt the same impression over and over. It’s not the kind of art Henson produced. It’s very un-Muppet.

What it is, though, is very, very Disney — not in the original spirit of Walt, but in the style of a corporation that runs on licensing. This is “art” defined as mass duplication, not wonderment. It is the art of selling Tigger toys to millions of people all over the country who have houses filled with Tigger toys. I’ve always wondered who these people are: the people obsessed with Tasmanian Devils, who keep Mickey memorabilia rooms. Perhaps they are people who do not want to see the human effort behind the fantasy. To many, it must spoil the magic to picture a white-bearded Jim Henson standing underneath the last gelfling child in The Dark Crystal. For me, though, that scene multiplies the meaning of what came before. For that reason, I’ve given a pass to having a room full of Kermit toys. They might be a joy to collect, but where would I put them all? And where would my money go? To fund more great Muppet shows or to market more useless products?

For Death, We Have Birth To Blame

To demonize is to become the demon. Deep down, I know this, and as “Fraggle Rock” teaches, there are no evil villains, just hapless neighbors too confused to live in harmony. Ultimately, the only one we have to blame for the Muppets’ predicament is Jim Henson, and for what would we blame him? For creating a character that was so loveable and so tied to his being?

What makes great art often unsettling to contemplate is the palpable presence of the generous hand behind it, a hand that is, just like us, mortal. No matter how great, all artists die, and despite the dedicated efforts of many talented people, the Muppet moment has died. All the keepsakes in the world won’t change that. This is okay, even desirable, because it means a new moment might surface at any moment. It just won’t look anything like the old one.

Who knows, it might even look like Segel’s movie, but only if he can treat the Muppets the way the Muppets treated Disney World. That is, completely irreverently.

Segel’s criticism of the recent Muppet movies misses the mark slightly. What is most disappointing about the post-Henson movies is not their reliance on weird concepts, but their lack of character-based humor. There have been some moments of genuine art in the last twenty-one years. In Muppets From Space, Bobo Bear’s interplay with Jeffery Tambor contains echoes of Ernie-and-Bert banter. Gonzo has never wavered in his dedication to… Gonzoness. But these days Kermit offers out-of-character wisecracks like, “Get down with your bad selves.” This isn’t Kermit’s humor. Kermit was a square, but he was never one-note dorky, a depository for one-liners and pop-culture satire. That line could have been plucked from Steve Urkel, from “ALF,” from any sitcom from ’78 on. That’s what’s disappointing. A character without specificity is not one.

Change Is Bad And Beautiful

When you consider how long Henson, Oz, Juhl, Nelson and Goelz worked together, it’s not surprising that their characters can respect and resent one another so believably, so humanly. The Muppets had 20 years to develop their web of interpersonal relationships. I watched one reel of 2000s-era DVD Extras where the only discernable joke was an endless riff of Piggy fat jokes. Pre-1990, Piggy’s zaftig persona was gently mocked. Now, the fat-jokes feel like the lead-up to a gang-bang. It’s bigoted and sour; more indicative of Gen X’s snickering than the Silent Generation’s gentle absurdism. Post-Henson Muppet humor is harder, meaner and more unforgiving. It’s snarky like Bill Maher. And while many Muppets fans will forever think of Brian Henson as the little boy on “Sesame Street” astonished to find “Three peas?!” it’s important to remember that when free to create his own project, he produced Unstuffed and Unstrung, an adults-only “Henson Alternative.” This is not entirely a complaint. While the improv show is in some ways the epitome of un-Muppet (it has no page on the Muppet wiki), it’s exactly the way a Muppeteer should evolve.

When Piggy first appeared in a TV special hosted by Herb Alpert in 1974, she was voiced by Jerry Nelson, and she was a demure ingÈnue who couldn’t sing to save her life. Then, in the first season of “The Muppet Show,” for the first handful of episodes, Piggy was performed by Richard Hunt. Hunt does a great brassy Janice, toadying Scooter, and curmudgeonly Statler, but Piggy was not to be his. Hunt’s Piggy was husky, whereas Oz, who took over in 1976, started much higher, in almost a squeal. It was Oz who introduced the great tic of slipping “out” of character and letting his non-feminine voice crack through at times. Whereas Hunt had a more seamless entertainer’s voice — he was a real showman, a song-and-dance man whose characters seemed to be clowning — Oz gave the character something different. In Oz’s early years with the Muppets, in the ’60s, he played a princess pretty straight — all falsetto. But after a decade of experience, he wisely let Piggy break character, like a drag queen’s indiscretion or a woman dropping the mask of sweetness. Oz’s voice gave the character its dimension, and because of that, the voice we think of as Piggy is forever tied to Oz, even if today, she is almost always voiced by an Oz-a-like, Eric Jacobson, who took over from Oz in 2002. They are all Muppeteers, but no one matches the level of sophistication Oz brought to the role, and they likely never will, because these days no one is really trying to go beyond imitation.

No Man Is A Muppet

But this is where I get confused. Muppets are an especially collaborative art. In Emmet Otter’s Jug Band Christmas, Ma Otter was performed by Oz, but overdubbed with the voice of a natural singer, Marilyn Sokol. This was also the case with “Fraggle Rock”’s Junior Gorg — the dancing fool is not the same man as the clowning “aw gee” voice. So can we say a character is the province of one person when it was sketched by Henson, created by a team of puppet-makers, clothed by costume designers, its technology engineered by technicians, its body performed by a mime, its face controlled by a Muppeteer and its voice overdubbed by an actor? Where does a Muppet really begin?

And who gets credit when two characters share what is almost one voice, like the two vermin that live in the trash heap of “Fraggle Rock”? One is Goelz, the other Hunt. But they are playing off one another’s tics and nuances to the extent that they are almost twins. The same holds true with Statler and Waldorf, as each one strives to out old-man the other.

I suppose what I’m saying is that the evolution of characters requires a healthy community and a public domain. Oz’s Cookie Monster owes a lot to Henson’s Munchos monster, from his early commercial work. Uncle Traveling Matt Fraggle sounds a lot like Henson’s reportorial Newsman combined with Henson’s gruff piano-man, Rowlf the Dog. Many of Goelz’s dumber characters, such as Wendell Porcupine and Beauregard seem to echo Henson’s ogre from “Tales from the Tinkerdee” a decade before. No one really has claim to inventing slow-wittedness or ogrishness as character traits. These are common human failings. They’re stock. Each of the Doozers does its own version of nasal dweebishness, and each Fraggle, brash, earnest bonhomie. Developing character is neither linear or ascribable.

In 1990, the Muppet universe was already full of copycat frogs. There is the palace frog choir in “The Frog Prince,” the advertising frogs in The Muppets Take Manhattan, and Kermit’s swampland cousins in The Muppets at Walt Disney World. Every Muppeteer has at one point or another done Kermit’s signature epiglottis-formed drawl. This world of tribute-Kermits, this is the way creativity really flourishes, not by one-for-one exchanges, as with Henson-for-Whitmire, but by a more organic reproduction, like leaves on a branch, bunnies in a warren, the dizzying exponential growth of bacteria in a Petri dish. These corporations misread our love of Kermit’s character. Did we really want Photocopy Kermit? Or did we want the multiplicity of life?

Break Him Out Of The Windowless Tower

To make the new Muppet movie an artistic success, Segel has an uphill battle. The premise looks good — a fuzzy young man seeks to reunite the Muppets, the only people “like him” that he’s ever come across. Segel has chosen a no doubt heartfelt and powerful engine — weirdo’s nostalgia — to drive this plot. But Jerry Nelson is 76. Dave Goelz is 64. If they play Statler and Waldorf, they will be as old as the old guys they play. Will the Muppets be treated as immortal effigies to be filled by any impressionist’s hand-for-hire, or will they acknowledge that time does indeed pass and moments do in fact die?

One hopeful sign is that the film will feature original music by “Flight of the Conchords”’ Bret McKenzie and will be directed by that series’ pitch-perfect director, James Bobin. That said, The Muppet Christmas Carol also had an original score by the classic Muppet songwriter Paul Williams, and that didn’t matter. The studio’s final arrangement was so over-produced that his idiosyncratic touch was lost. For some reason, studios seem to think we all want to hear movie scores that sound like every other movie score when really I just want to hear forty people in a room together singing “Rainbow Connection,” imperfections and all. In fact, all I want to hear are imperfections. They show you tried something beyond your abilities. “Rainbow Connection.” Now that was really something.

They got it wrong with Kermit. What made him great wasn’t his design or his funny glottal affectations. It was his sense of humor. Humor is intangible, and it can’t be copyrighted, licensed or sold. As a society, we have come to use copyright like plastic — to prevent spoilage and feed our illusions of immortality, but there is no act of congress that will stay death’s hand. When someone is dead, you don’t get them back — not in this world. They may pass into myth, but walk, talk and sing, no.

Elizabeth Stevens’ fiction appears in Explosion-Proof magazine

under the name Gordon Ebenezer Gourd. Please visit Mr. Gourd and take his semicolon challenge.

Watercolor illustration by Chris Cooley, used with permission. Many other images via Muppet Wiki.