The Vasa Museum: All Hail The Ship That Never Made It A Nautical Mile

The Vasa Museum: All Hail The Ship That Never Made It A Nautical Mile

by Elisabeth Donnelly

In 1628, the Vasa Warship set off on its maiden voyage in Stockholm harbor, aiming towards Poland. Made from the hull of over 100 oak trees, it was outfitted with 64 cannons and had masts over 160 feet high. After traveling 1,300 meters — less than a nautical mile — the ship met a strong breeze, foundered and sank. The Vasa was, in every way, a failure. So of course it has, since 1990, had its own museum, where visitors to Stockholm can go to see what a gargantuan example of 1600s-style hubris looks like. Salvaged from the sea floor in the early ’60s, the ship stands at the center of the museum, largely intact, with 95% of its original wood. It’s a scientific marvel. An archeological wonder. Truly a treasure and record of a forgotten time.

For the Swedes — or at least, my small, biased sample of relatives, bursting with national pride — the Vasa Museum occupies a space between tourist oddity and honorable symbol of a rich heritage. Sort of like the Mütter Museum of medical oddities in Philadelphia, if the Mütter Museum was both a tourist oddity and also carried the symbolic weight of a King’s wartime ambitions. You might think of the Titanic replicas in Branson, Missouri, and Pigeon Forge, Tenn., as parallels, but really those are just the past re-imagined as camp. The Vasa Museum occupies a different sphere, straddling history, science, archeology and mystery all at the same time.

It is also, undeniably, hilarious. Super funny. The type of place where you look at the exhibits and you giggle. You titter. I visited it this year and could barely contain myself. It is not a classy sort of laughter, laughing at someone else’s failure and their subsequent celebration of it. But keep this in mind: The Vasa Museum is a giant room dedicated to a war ship, a symbol of a country’s might and colonialism, that ended up at the bottom of the ocean. When the Vasa was setting out on her mission of failure, the Pilgrims had just created the most delicious holiday of all: Thanksgiving. (Take that, Vikings, Skarsgards and Robyn!)

When you walk through the doors, the air smacks you, a fine, humid spritzer of mist flavored with chemicals, the putrid-smelling soup that preserves the ship. And you see her: the Vasa in all her 383-year-old glory. She’s basically the boat equivalent of a bitsy Hollywood hanger-on who just had a crazy boob job. Top-heavy. The hull of the ship is small and the top is laden with sculptures and ornamentation. It’s easy to see why it sank.

The museum winds around the ship, floor by floor, like a spiral. We admired the spectacular view of the Vasa and the tiny little baby replica in front of it, and then were shuttled into the children’s section, whole rooms given over to the creepy recreation of ye olden days. Mostly this section consisted of life-sized statues, a room with a diving bell that you can step into (a creepy, disconcerting experience of darkness), and enigmatic, koan-like sayings on the walls: “HOW COULD THIS HAPPEN? Was it the wrath of God or the malice of Poland? Was the crew drunk or was the Vasa wrongly built? The town was rife with rumors.”

After looking at the dolls and statues, speeding by the Vasa video that loops in English, Russian and Swedish, I happened upon the floors devoted to ornamentation, which were fascinating for a variety of reasons. While the Vasa itself is in amazing shape, the 500 sculptures that once adorned are less so, having been corroded by 300 years under the sea. Walking among them, I noticed a variety of melting faces, former angels rendered grotesque over the years, their fine details fading into a uniform gauzy yellow because they’d lost their pigment. All these decorations were a tribute to the all-consuming power and wonderfulness of Sweden’s then-monarch, King Gustav II Adolph. Heroes like Hercules and lions shared space, symbolizing the bravery of Sweden. In one tableau, they’re trampling a Polish man flat on his back, because Sweden’s going to win. Cherubs bless the boat for the sake of Sweden.

Every bit of the art is laden with symbolism, but the best bit is that on the side of the beakhead, at the front of the ship, the King ordered twenty busts of Roman emperors from Tiberius to Septimus, because he wanted to communicate that he was next in line. I wandered among recreations of these sculptures, reading heady explanations of the role they played in announcing someone’s power. The sculptures were old and elegant. It was as if I was transported back in time, to the 1600s. Then I looked at the far wall and there was a black-and-white glossy of Arnold Schwarzenegger dressed up as Conan the Barbarian, haphazardly pinned up.

Once I came upon the top floor of the museum, there was an eagle’s eye view of the ship and masts pinned to the walls, a fine spidery lace six times my height. It was impossible not to marvel at how they managed to be preserved.

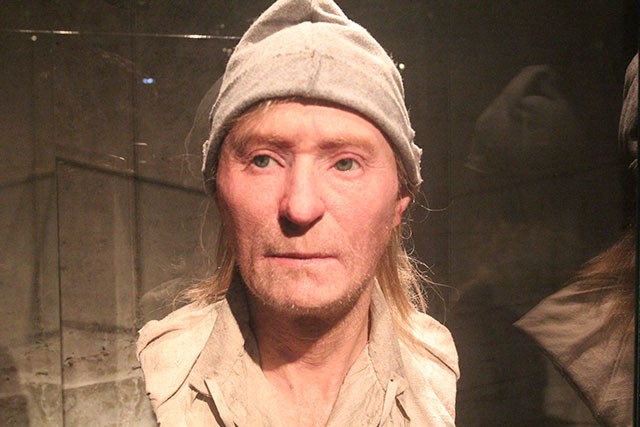

I had not conquered the whole of the Vasa, however, and I took an elevator down to the basement floor, which had a ground’s-eye-view of the ship. The exhibit there has completely fascinating details on the science of preservation and how, exactly, the museum’s able to keep these treasures in existence. Among the iron and the gaudy details, there was another bit of buried treasure: a collection of bones from the people who died on the ship. Scientists had cobbled together data and stories about the Vasa’s dead, and this information had been used to create terrifyingly realistic 3-D busts of what these skeletons may have looked like as actual people on the ship, complete with eyeballs that… looked like eyeballs. They will haunt my dreams forever.

Another exhibit was centered around how boats are found in brackish water. There were pictures of hot Swedish divers from the 1950s, all working for amateur archeologist Anders Franzén, who was on a mad mission to find the boat, after concluding that it had to still be there in the harbor, preserved in the cold, brackish waters of the Baltic Sea. It was an adventure story, as if it sprang from a book about a man with a crazy, impossible dream just waiting to happen.

As a monument to failure, the Vasa Museum was the very opposite of any concept I’ve ever had of a historical museum — after all, I’m from Boston, where history is devoted to winning and fighting (these days, sigh, even the sports teams from Boston are winning). It is hilarious in concept, hilarious in its national hubris, and, by the time you wind around to the straight-up science on display, completely fascinating. You go in ready to giggle, and you come out having learned something. It may be my favorite museum in the world.

Elisabeth Donnelly’s favorite Skarsgard is Stellan.

Photos by Stu Sherman, used with permission.