I Love You Christopher Hitchens, You Irritating Bastard

I Love You Christopher Hitchens, You Irritating Bastard

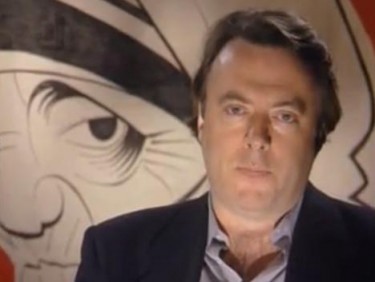

Christopher Hitchens, along with Robert Hughes and Spy magazine’s Michèle Bennett, first started me imagining that I would like someday to be a journalist and critic. These jaundiced observers of the follies of the late 1980s and early 1990s had in common an elegant style of attack, and a positive relish in the peppering, roasting, carving and dishing up of sacred cows. Hughes, by far the most scholarly of the three, went on to produce magnificent books and documentaries (and to survive the terrible injuries he sustained in a super-hairy car crash in 1999); Bennett’s true identity has never been revealed, but I hope he or she is thriving, and writing still. I like to imagine I’ve been enjoying the Bennett oeuvre all along, under some other august byline. But Christopher Hitchens! Ach, Christopher Hitchens. How I have loved him, despite the ordeals he has put me through. He’ll go and be a fearful crank about atheism or “Islamofascism” for ages and I get all mad, and then he writes this freaking brilliant column about the Murdoch scandals and I’m crazy about him again. Old loves are like that.

In the Feb. 1995 issue of Vanity Fair, a memorable Hitchens piece described the aftermath of the Channel 4 broadcast of Hell’s Angel, a blistering half-hour takedown of Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Written by and starring Hitchens, produced by Tariq Ali, marred by a terrible soundtrack and viewable on YouTube, Hell’s Angel exposed Mother Teresa’s ties to various despots and thieves, and questioned the wisdom of handing out the Nobel Peace Prize to a woman whose famous clinic for the poor had repeatedly been found unsanitary and badly run, refusing, for example, to give painkillers to the dying — maybe because she really did believe, as she once said, that “[t]he suffering of the poor is something very beautiful.”

In this VF piece Hitchens recounted with unmistakable delight the media rumpus occasioned by Hell’s Angel. “Fleet Street in full cry, going at it foot, horse and guns. Many yells of delight and relief that someone has finally pulled the chain on the ghoul of Calcutta, but many outraged squeaks and howls about my lack of chivalry. […] Best of all, a cartoon in The Spectator saying that the Hell’s Angels have complained.” Already you could see that he loved being (a) on TV, (b) notorious and (c) lambasted, in this case by the horrified fans of Mama T., as he called her. Here was a foretaste of the name-dropping polemicist to come. But the writing had terrific style and bite, and wonderful jokes, too, including one regarding his description of Mother Teresa (born Agnes Bojaxhiu in 1910) as “a presumable virgin”:

Yet another BBC interviewer makes much of this moral loophole, demanding to know how I can know anything about Mama’s intactness. Losing patience, I say that the whole point is that I don’t know. Who can say what happened with the dashing boulevardiers of Skopje when Agnes Bojaxhiu was but a pouting and trusting lass?

Good as all that was, the piece stood out in my mind for the next sixteen-plus years for another reason entirely. Hitchens wrote,

In the old days of Private Eye, the great Claud Cockburn would sit the team of hacks and satirists around the table and say, “Right. Who does everybody think is wonderful? Who gets a free pass?”

The talk would run on, the hacks mentioning this name and that, until someone said, “I know! Albert Schweitzer!”

“Good, then,” Claud would say. “Let’s have a go at old Schweitzer.”

In our own day, scandals like the ones at the News of the World (and earlier, those at the Times) have drawn attention to the sometimes blurry line between hard-hitting investigative brio and depraved, careerist corporate hackery. Hitchens’s then-paradoxical combination of total irreverence for every sacred institution and total reverence for revealing the truth was, and remains, irresistible. If I were to claim a personal manifesto for the practice of journalism (I won’t, but if), Cockburn Sr.’s remarks would describe it perfectly. There’s a vast difference between tabloid scandal-mongering, which is done for money and is despicable, and exploding the lies we are continually told by and on behalf of the Man, which is crucial, and worthy.

Earlier in his career, Hitchens hewed to this line, arguing passionately for the return of the Elgin Marbles to Greece in his 1987 book, Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles, and railing against the British monarchy in The Monarchy: A Critique of Britain’s Favorite Fetish (1990). I especially loved hearing his howls of rage against Kissinger, which were certain to appear at the slightest mention of the old war criminal’s name.

All of which is to say that the gift of Hitchens to the readers of this earlier period was a bone-deep and abiding skepticism. A real reason for going after all the muck that’s fit to rake.

WAR, HUH, GOOD GOD

Hitchens’ post-9/11 support of the Iraq War caused many admirers to desert him in dismay. But Hitchens’ true crime was not his support of the war, for which he became a cheerleader almost from the start. It was his betrayal of skepticism itself.

In his 2010 memoir, Hitch-22, he relates how his politics changed as he watched the Twin Towers crash down.

I was very suddenly and very overwhelmingly actuated by pity. I know that this is the pathetic fallacy at work and I daresay I knew it then, but it was like watching the mute last moments of a dying elephant, say, or perhaps a whale. At any rate, the next emotion I felt was a rush of protectiveness, as if something vulnerable required my succor. Vulnerable? This commercial behemoth at the heart of an often-callous empire? Well, yes, at the risk of embarrassment. […]

From an early age, I had dreamed of Manhattan and identified it with breadth of mind, with liberty, with opportunity. Now it seemed that there were those who, from across the sea, had also been fantasizing about my longed-for city. But fantasizing about hurting it, maiming it, disfiguring it, and bringing it crashing to the ground […] Before the close of that day, I had deliberately violated the rule that one ought not to let the sun set on one’s anger, and had sworn a sort of oath to remain coldly furious until these hateful forces had been brought to a most strict and merciless account.

From here he launches into a defense of his newfound flag-waving and war-mongering. One of the principal arguments in Hitch-22 is a highly questionable one, viz., that the author knows more about the Middle East than do us bumpkins who “weren’t there”; because he has traveled in and reported extensively on the Middle East, he has access to knowledge denied most of the rest of the world; he knows for sure that those Islamofascists are Evil with a capital E and need to be stamped the hell out. The fact that there were many, many others with equally immediate and/or specialized knowledge, such as Brent Scowcroft and a load of generals and diplomats who were also “there,” who had sky-high security clearances and still opposed the war, goes unspoken.

Scott Lucas’ book, The Betrayal of Dissent: Beyond Orwell, Hitchens and the New American Century is a really splendid, well-reasoned, painstakingly thorough account of the run-up to the war. Lucas goes unerringly after the failure of Hitchens and others to acknowledge that wrongheaded U.S. policies might be even partly responsible for anti-U.S. sentiment in the Middle East in general, and for the crimes of 9/11 in particular. And Hitchens’ “Mission Accomplished” moment in November of 2001 regarding the alleged victory in Afghanistan (“Well, ha ha ha and yah, boo”, he crowed) comes in for a well-deserved bashing.

Many public intellectuals were swayed by the lies of the Bush administration before the war, the worst effect of which was that their eloquence and rhetorical skills were used to muddy the waters of the debate. Many a Republican cousin of my own relied on the pronouncements of Hitchens or of Andrew Sullivan to score a point at Thanksgiving dinner. Lucas remarks on this, too, in The Betrayal of Dissent: “Hitchens and his American peers assumed an important role in the War on Dissent by providing an alternative ‘Left’ which could be embraced.” In effect, these writers were playing Saruman to the Sauron of the politico-military-industrial complex.

It’s startling to compare Hitchens’ continued loyalty to “the sort of oath” he swore on 9/11 with Andrew Sullivan’s March 2006 recantation in Time, “What I Got Wrong About the War.” Here, Sullivan focused on three “huge errors” made by conservatives in the run-up to the catastrophe. First, overestimation of the competence of government (“We got cocky”); second, “narcissism,” a blindness to “the resentments that hegemony always provokes” among America’s friends as well as its foes; third, a misunderstanding of culture: “There is a large discrepancy between neoconservatism’s skepticism of government’s ability to change culture at home and its naiveté when it comes to complex, tribal, sectarian cultures abroad.” He went on to enumerate some of what he saw as the positive effects of the American invasion, concluding that it was too early yet to say that we have failed.

In 2001, Andrew Sullivan literally wrote against dissent in the “watch what you say” vein popular among conservatives before the war: “The decadent left in its enclaves on the coasts is not dead — and may well mount what amounts to a fifth column.” An evolution as profound as Sullivan’s really shouldn’t be a mere matter of “changing sides” as if one were talking about football teams; that would only be exchanging one dogma for another. Just because progressives and Democrats were right before the war, it does not follow that they will be right all the time, so it won’t do to switch sides from black to white, when what you have come to realize is that there are shades of grey.

I wrote to Sullivan and asked him how he felt about his 2006 piece in Time, and he replied (email edited for punctuation):

I stand by everything I wrote then. I remain glad that Saddam is gone, but the costs of the war far exceeded its benefits, and the collateral damage to so many civilians and soldiers will always trouble my conscience. I remain ferociously anti-Islamist, but have come to see the perils of mere military action in the long war on Islamist terror; and of taking Washington conventional wisdom for granted.

Far from taking the Sullivan route, Christopher Hitchens more or less doubled down on his earlier suggestion that Saddam Hussein was possessed of WMD in Hitch-22, despite what Hans Blix or anyone else had been able to produce in the event.

Underneath a Sunni mosque in central Baghdad, the parts and some of the ingredients of a chemical weapon had been located and identified with the help of local informers. I was told this off the record, and told also that I was not to make any use of the information. It was thought that, when the use of a holy place to hide such weaponry was disclosed by the intervention, it would help to change Muslim opinion.

Really! “Ingredients”?! And to have made such discoveries at the bargain-basement price of $785 million and counting! #whoa

(Just as an aside, I was also bummed to note the absence in Hitch-22 of loose cannon and super-lefty George Galloway, the independent MP for Bethnal Green and Bow who, in 2005, reduced then-Senator Norm Coleman to a tiny little heap of ash after giving the best address to Congress I have ever seen. But Galloway’s takedown of Hitchens was equally remarkable. “You’re a drink-soaked former Trotskyist popinjay!” he shouted. For once Hitchens had zero comeback. “Your hands are shaking! You badly need another drink.”)

The real trouble is that on 9/11, I guess, or around then, Hitchens started making statements like, “Only a complete moral idiot can believe for an instant that we are fighting against the wretched of the earth. We are fighting […] against the scum of the earth.” (“It’s a Good Time for War,” Boston Globe, September 8, 2002.) This obtuse self-certainty represents the dead opposite of the original Hitchens way of going about things, at least as I understood him. Suddenly he was all, we smart people will figure it out for you little people! We have heroisms and slogans! We are Vulcans and/or super-atheists and you are just there to listen to our opinions and buy our books. How attractive it must have been, how tempting, to be so certain.

Some people feel more comfortable in a black and white world, but it had been Hitchens himself who had early taught me to prefer grey, and only grey; to hold both black and white in your mind together, to appreciate the way they are washed into one another, mixed in like Stoppardian jam into the porridge, impossible to separate or even define. But then he left that world of infinite shades.

“A CRUDE EXISTENTIAL MALPRACTICE”

Hitchens’ blind faith in the rightness of his own opinions seems to originate in his hatred of religion; a hatred formed in the standard “opiate of the masses” manner of Marxists everywhere, which over time mutated into this anti-religious fury that blames every bad thing that has ever happened on religion. The religious are Hitchens’s shadow figures; he ridicules their certainties while positively wallowing in certainties of his own.

The atheistical triumvirate of Hitchens, Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins has done a good deal to set back the clock on real skepticism. The smugness with which these guys take to the airwaves is repellent enough, but really, first off, they need to stop calling themselves skeptics. Because they really, really believe in something.

god is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, Hitchens’ best-selling diatribe, enumerates his (quite justifiable) hatred of the crimes committed in the name of Christianity, Islam, Judaism, etc., without bothering to acknowledge that the cruel and greedy will twist any institution at all, religious or secular, to suit their purposes. All three authors appear to believe that Islam, Christianity, Judaism, etc., are literally evil organizations.

Can these authors (one of whom wrote The Selfish Gene, one of the most fascinating and brilliant books of the last century,) really be so boneheaded as to fail to understand that every institution, political, academic or religious, can be, and has been, ennobled by free-thinking, brilliant men and women as often as they have been perverted by criminals and thieves and idiots? Yes, there is Pat Robertson, and there is Fred Phelps, and there are also Dr. Rowan Williams and Reinhold Niebuhr and Bishop Fuglsang-Damgaard and countless principled and even heroic men and women of faith, it seems ridiculous to have to say.

The Dialectic of Secularism, Jürgen Habermas’ 2007 dialogue with the odious but far from stupid Papa Ratzi, is one katrillion times more satisfying intellectually, better reasoned and more exciting re: the possibility of a new Enlightenment than anything the Super Atheist Triumvirate has come up with. In 1999, Habermas said in an interview:

For the normative self-understanding of modernity, Christianity has functioned as more than just a precursor or catalyst. Universalistic egalitarianism, from which sprang the ideals of freedom and a collective life in solidarity, the autonomous conduct of life and emancipation, the individual morality of conscience, human rights and democracy, is the direct legacy of the Judaic ethic of justice and the Christian ethic of love. This legacy, substantially unchanged, has been the object of a continual critical reappropriation and reinterpretation. Up to this very day there is no alternative to it. And in light of the current challenges of a post-national constellation, we must draw sustenance now, as in the past, from this substance. Everything else is idle postmodern talk.

Compare this with Hitchens’ bald assertion in god is not Great that “Religion Kills,” or with this, from his introductory chapter: “[P]eople of faith are in their different ways planning your and my destruction, and the destruction of all the hard-won human attainments […] Religion poisons everything.”

god is not Great is full of this adolescent stuff. But then Hitchens lowers his fists for a moment, and you will find a beautiful and interesting passage like this one, on page 121, about John 8:3–11 (the “he that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone” part):

An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth and the killing of witches may seem brutish and stupid, but if only non-sinners have the right to punish, then how could an imperfect society ever determine how to prosecute offenders? We should all be hypocrites. And what authority did Jesus have to “forgive”? Presumably, at least one wife or husband somewhere in the city felt cheated and outraged. Is Christianity, then , sheer sexual permissiveness? If so, it has been gravely misunderstood ever since. And what was being written on the ground? Nobody knows, again. Furthermore, the story says that after the Pharisees and the crowd had melted away (presumably from embarrassment), nobody was left except Jesus and the woman. In that case, who is the narrator of what he said to her? For all that, I thought it a fine enough story.

But instead of being fans of the King James Bible or of the Dalai Lama or whatever, Hitchens mawkishly advises that we seek the infinite in “the beauty and mystery of the double helix” instead. Why not a rose? Seriously.

THE EDEN OF BLANDINGS CASTLE

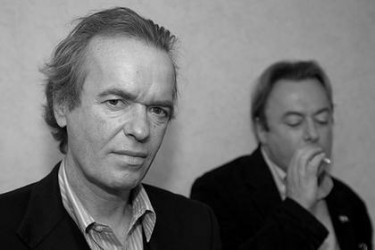

The character of Hitchens recalls a lot of larger-than-life figures. One is James Boswell, because he too was a reckless, dissipated and passionate man who attached himself to a writer of less skill but far greater renown than himself (I can think of no other context in which Martin Amis could legitimately be compared to Dr. Johnson, but in this one instance he really can). Hitchens is also like any number of Bloomsburyites, Apostles or Bright Young Things; one could easily imagine him in the pages of Dance to the Music of Time, a type somewhere between Quiggin and Stringham, chasing Pamela Flitton around.

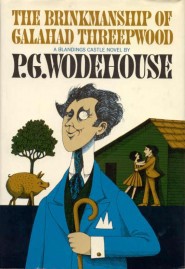

But most of all, Hitchens recalls another fictional character: one of Wodehouse’s finest creations, and the literary personage whom, I suspect, Hitchens himself would most like to resemble (he is known to be a great admirer of Wodehouse). I refer to the Hon. Galahad Threepwood, the younger brother of the Earl of Emsworth, an elegant, witty bon vivant of that earlier fin de siècle.

Everything about this Musketeer of the nineties was jaunty. It was a standing mystery to all who knew him that one who had had such an extraordinarily good time all his life should, in the evening of that life, be so superbly robust. Wan contemporaries who had once painted a gas-lit London red in his company and were now doomed to an existence of dry toast, Vichy water, and German cure resorts felt very strongly on this point. A man of his antecedents, they considered, ought by rights to be rounding off his career in a bath-chair instead of flitting about the place, still chaffing head waiters as of old and calling for the wine list without a tremor.

This is how characters in Wodehouse novels spend their autumns. As Evelyn Waugh, whom Hitchens also admires, said so famously:

For Mr Wodehouse there has been no fall of Man; no ‘aboriginal calamity’. His characters have never tasted the forbidden fruit. They are still in Eden. The gardens of Blandings Castle are that original garden from which we are all exiled. The chef Anatole prepares the ambrosia for the immortals of high Olympus. Mr Wodehouse’s world can never stale. He will continue to release future generations from captivity that may be more irksome than our own. He has made a world for us to live in and delight in.

Wodehouse’s is a dream world where you can smoke and drink for decades on end and never get cancer, and where everything else comes right eventually, too. Its charm and naiveté mirrors the essential Hitchens worldview, what with its unending evenings of revelry and schoolboy cheek and hobnobbings with the rich, brilliant and crazy, with its maybe foolish trust in the possibility of knowing the good guys from the bad, or right from wrong.

Galahad Threepwood is a friend of star-crossed lovers, the personification of kindness and gallantry — and a writer. Two of Wodehouse’s best novels, Summer Lightning and Heavy Weather, center on the potential publication of Threepwood’s scandalous “Reminiscences,” the prospect of which scares every character liable to be mentioned therein (pretty much all the olds) into all kinds of improbable antics. It is understood however that, though many moved heaven and earth to ensure that the “Reminiscences” remained secret, they were as red-hot as advertised by those few who’d read them. It pains me to relate that the same cannot be said of Hitch-22.

The love of Christopher Hitchens, so big and so freely given, makes him lovable still. There is a lot to enjoy in the book. But taken as a work of literature (as opposed to a political polemic, which I am probably done yelling about) the chief sins of Hitch-22 are those of omission.

This memoir is not so much a memoir as a mash note to all the fabulosos whom Hitchens has befriended, but most of all to Martin Amis, the love of his life. The “small but perfectly-formed” Amis rates not only his own chapter of Hitch-22, he is mentioned on page after page. By contrast, Hitchens’ wives and children are all but absent, undrawn, ciphers almost. The epigraph of the Amis chapter is a quote from Amis himself: “My friendship with the Hitch has always been perfectly cloudless. It is a love whose month is ever May.” (That is not quite true, I think. There was a spat over Stalin in there somewhere.)

There are also ungenerous descriptions of Martin’s father, the great novelist Kingsley Amis, who’d become in Hitchens’ estimation “an elderly man, querulous and paranoid and devoid of wit”. Apparently the boys once got sore when Amis Sr. took them to see an Eddie Murphy movie. The old man had become coarse and racist, Hitchens says, and no fun anymore. The fact that Kingsley Amis found his son’s novels unreadable (and often said so in public) goes unremarked, which is really grating. There was clearly more than one reason for the coolness that developed between father and son. For all that, though, there is a spectacular description of the “golden late summer” when the two Amises were very close.

“Dad, will you make some of your noises?” It was easy to see, when this invitation was taken up, where Martin had acquired his own gift for mimicry. Kingsley could “do” the sound of a brass band approaching on a foggy day. He could become the Metropolitan line train entering Edgware Road station. He could be four wrecked tramps coughing in a bus shelter (this was very demanding and once led to heart palpitations). To create the hiss and crackle of a wartime radio broadcast delivered by Franklin Delano Roosevelt was for him scant problem (a tape of it, indeed, was played at his memorial meeting, where I was hugely honored to be among the speakers). The pièce de résistance, an attempt by British soldiers to start up a frozen two-ton truck on a windy morning “somewhere in Germany,” was for special occasions only. One held one’s breath as Kingsley emitted the first screech of the busted starting-key. His only slightly lesser vocal achievement — of a motor-bike yelling in mechanical agony — once caused a man who had just parked his own machine in the street to turn back anxiously and take a look. The old boy’s imitation of an angry dog barking the words “fuck off” was note-perfect.

PAIN WE OBEY

In August of last year, Twitter lit up with a link to Hitchens’ blog at Vanity Fair, where he had announced, with characteristic flamboyance, that he’d been diagnosed with esophageal cancer (he is currently in a course of experimental treatment).

He is one of the only writers in the world who could make such an announcement fun to read.

I have more than once in my time woken up feeling like death. But nothing prepared me for the early morning last June when I came to consciousness feeling as if I were actually shackled to my own corpse. The whole cave of my chest and thorax seemed to have been hollowed out and then refilled with slow-drying cement. I could faintly hear myself breathe but could not manage to inflate my lungs. […] Within a few hours, having had to do quite a lot of emergency work on my heart and my lungs, the physicians at this sad border post had shown me a few other postcards from the interior and told me that my immediate next stop would have to be with an oncologist. Some kind of shadow was throwing itself across the negatives.

The previous evening, I had been launching my latest book at a successful event in New Haven. The night of the terrible morning, I was supposed to go on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and then appear at a sold-out event at the 92nd Street Y, on the Upper East Side, in conversation with Salman Rushdie. My very short-lived campaign of denial took this form: I would not cancel these appearances or let down my friends or miss the chance of selling a stack of books. I managed to pull off both gigs without anyone noticing anything amiss, though I did vomit two times, with an extraordinary combination of accuracy, neatness, violence, and profusion, just before each show. This is what citizens of the sick country do while they are still hopelessly clinging to their old domicile.

The heartbreaking thing is that there is video of him online on that very day. He’d been in the hospital that morning and had the fluid pulled out of his lungs, and then he went on “The Daily Show” late that same afternoon. It’s knee-weakening to watch, knowing he’d only just finished yawking his guts up moments before he walked onstage.

“You haven’t taken it easy on this model, body, that you have,” observed Stewart.

“No.”

“Yet you don’t look like shit. And you should … it’s somewhat upsetting.”

“There’s crying inside, A, and B, there’s an oil painting up in my attic that is beginning to look distinctly … seedy, I think you might say.”

“EVEN THE ENQUIRER IS CHARMED”

The literary and cultural critic, full of subtlety and heart, vs. the religio-political polemicist, bullying and pigheaded, full of wanting to have his way at all costs. A creature of the most extreme contrasts. Childlike and wondering, haughty, combative, his cool Oxford contemplativeness at fatal odds with the nearly incoherent, raging casuistry.

Even when I have longed to clock this author over the head with a brick (a frequent occurrence), he has always been so much fun. And I could never deny the clarity and charm of his voice. That’s why people really, really don’t want him to die; you have to look pretty far for anything but wishes for a speedy recovery in the comments in the cited VF blog post, despite all the complaints about his being a windbag, a sellout, a self-aggrandizing polemicist, and so on.

The title of Hitch-22 refers to the following paradox:

It’s quite a task to combat the absolutists and the relativists at the same time: to maintain that there is no totalitarian solution while also insisting that yes, we on our side also have unalterable convictions and are willing to fight for them. After various past allegiances, I have come to believe that Karl Marx was rightest of all when he recommended continual doubt and self-criticism. Membership in the skeptical faction or tendency is not at all a soft option […] To be an unbeliever is not to be merely “open-minded.” It is, rather a decisive admission of uncertainty that is dialectically connected to the repudiation of the totalitarian principle, in the mind as well as in politics.

So there is the matter of dialectic, in which both parties are presumed to care about the truth, no matter where it will eventually be found, and then there is debate, taking sides; the question of freedom of thought and expression invariably melding into the question of passionate conviction, passionately defended. Where doubt and faith collide. Because after dialectic, after having arrived at a conviction, it then falls to the combatants to fight those who resist the “truth”; no longer to doubt or continue to seek the truth, but to do battle for it. Hitchens, a born fighter, has an insufficient amount to say about the nature of his own faith in Hitch-22, sticking instead to a pretty hopeless insistence on himself as a “skeptic.”

As Scott Lucas put it in a recent email, “Whatever Hitchens’ merits as a polemicist, he does not ‘try and keep opposing ideas alive in the same mind.’ Arguably, his effectiveness is precisely that he does not do this — instead, he decides on one point of view (on a book, a film, Kissinger, Clinton, Iraq, Kosovo, God) and then tries to grind those who differ […] into the dust with his invective. […] Show me a passage from Hitchens on politics and point out where “there are no certainties” in his declarations — if you can find these, you are a much better literary detective than I.”

Maybe Hitchens’ career really is just about fame itself. Professional advancement in almost every field is about self-promotion, about “making a splash,” gaining notice, flattering the “right people” and all that. (At this he has ever excelled; a game of the Friday group at The New Statesman involved thinking up the least likely statement to be made by each of those present. For Hitchens: “I don’t care how rich you are, I’m not coming to your party.”) It’s a performance, too, an almost schoolboy rendering of “narcissistic vanity and the longing to be thought clever, smart and notorious,” as Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd described Hitchens in a 1995 TV column. And Scott Lucas has the same feeling, not just about Hitchens but about pretty much every pundit in Washington, New York and London, and it’s hard not to agree: “A commentator is usually not engaging with the purported subject at hand but using it to put himself/herself top of the totem pole.”

But there is the business, there is the performance of a journalistic persona, there is the professional bon vivant, and there is also the man, whose voice on the page is still so young and alive, and who belies all the bullshit sometimes, even now.

In a November 2010 debate at the Prestonwood Christian Academy (which is for the moment still available on YouTube, against the apparent wishes of Academy officials), Hitchens, who’d been debating with some Creationist or other, spoke directly to the young people in the audience (starting at around 4:33). He was ostensibly there to defend his atheism, but ended by encouraging these young people to live and think freely. I hope very much that this recording will be preserved and passed around a lot and shown to many, many more young people. It is crackling with excitement, conviction and beauty, it is passionate and moving.

[T]he offer of certainty, the offer of complete security, the offer of an impermeable faith that can’t give way, is an offer of something not worth having; I want to live my life taking the risk all the time that I don’t know anything like enough yet; that I haven’t understood enough; that I can’t know enough; that I’m always hungrily operating on the margins of a potentially great harvest of future knowledge and wisdom, I wouldn’t have it any other way, and I’d urge you look at those of you who tell you, those people who tell you, at your age, that you’re dead until you believe as they do — what a terrible thing to be telling to children — and that you can only live by accepting an absolute authority. Don’t think of that as a gift, think of it as a poisoned chalice; push it aside, however tempting it is. Take the risk of thinking for yourself. Much more happiness, truth, beauty and wisdom will come to you that way.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like A Gentleman, Think Like A Woman.