Going Home With Pulp

Going Home With Pulp

by Marlow Riley

Last Sunday, the third day of the Wireless festival in Hyde Park, I wandered through a crowd of around 50,000 people, past a crowded Fish & Chips stand, and a much less crowded “BBQ Burger” stand, past red-faced men swearing and carrying four pints of beer, and groups of healthy-looking European student-types sitting on blankets, to wait for a group of seven people from Sheffield to play their first show in London since 2002.

Both of these cities had loomed so large in my imagination for so long; London was, of course, London, but Sheffield was “Sheffield: Sex City,” as ludicrous as that may sound on its face. I was about to — finally — watch the band that made it that way: Pulp. So after the curtain fell and I joined the mass in singing, “You say you want to go home…” it was a surprisingly emotional moment. There were (possibly) drops of tears in the corners of my eyes and from the looks of it, a lot of others as well. It was mass euphoria, and if Jarvis Cocker wanted to start a revolution right then and there, we would have been his army.

***

I was an obsessive music fan from the beginning. I used to save up my allowance to buy children’s 45s and tapes, moved on to the Beatles, and eventually graduated to KROQ and the blue Trouser Press record guide, which is still the reason why I know who Blue Rondo a la Turk is. I had heard the Smiths and the Cure and the Ramones on the radio, but in this book were fascinating-sounding bands I’d never come across before, like the Fall and the Cramps. Three-quarters of the pages in that book were soon dog-eared, and the binding fell apart fast.

Growing up in a college town meant a record store with a good selection was nearby, vinyl was cheap, and a copy of Second Edition would only set you back a few dollars. Soon, Select and Melody Maker and NME found their way into my hands, opening up another world of bands called things like S*M*A*S*H and These Animal Men, who were playing something called the New Wave of New Wave. I never heard any of them until much later, but I dutifully bought my Ride albums and My Bloody Valentines and the first Blur record.

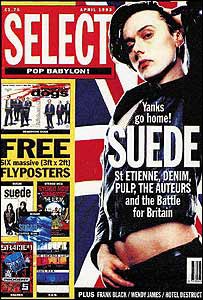

And then Britpop happened. Brett Anderson from Suede posed in front of a Union Jack on the cover of Select, which was taped to my wall by the end of the day. Suede, Elastica and Blur were offering me something I wasn’t getting from the US punk and indie bands I loved. They were stylish, they were cool, and they knew how to dress. Much as I loved Pavement and Jawbreaker and Dinosaur Jr., they wore t-shirts. Bands like Antioch Arrow and Swing Kids and the white-belts-and-Spock-hairdo crowd put a little more thought into it, and others had the manifestos and the uniforms, but it was all too serious. It looked like the UK was having all the fun. It seemed cosmopolitan, and even the Little Englandisms of dog tracks and the dole held a romantic allure to someone living 6,000 miles away.

At the head of the table sat Pulp, as far as I was concerned. Pulp offered a hero in Jarvis Cocker, who was witty and glamorous and free of the silliness of the other frontmen. He didn’t pose at bisexuality like Brett Anderson (“I see myself as a bisexual man who’s never had a homosexual experience”); he didn’t play dumb like Damon Albarn (“I started off reading Nabokov and now I’m into football, dog-racing, and Essex girls”); and he wasn’t a clown like the Gallaghers (all of it, really). He was too tall, too gangly, his fingers too long, to be a sex symbol. But he was. He was also too old (he was in his 30s before he had anything remotely like a hit). He was the smart outcast who showed that if you stick around for long enough, eventually everyone else would get it. In short, he was the perfect idol for a teenager who thought he was clever and different, but was, in reality, sort of annoying and obnoxious and probably shouldn’t have been smoking those colored cigarettes.

***

It felt like London was spending the entire weekend celebrating Pulp. (It wasn’t. The official subway announcements about the weekend’s big concert were the Take That shows at Wembley Stadium. Robbie Williams is back in the band, you know. English people find that, and him, relevant.) The obscure, so therefore cool, indie-pop/soul club How Does it Feel to be Loved? — the kind of place where Stuart Murdoch and Lawrence from Felt guest DJ — hosted an “Alternative Pulp Top Ten” night in a shabby back room of a pub, full of faded, seedy glamour and disco balls. Feeling Gloomy, a club night of “sad dance songs,” has their official Pulp celebration this coming weekend, but on Saturday, most of the crowd dancing to the Smiths and St. Etienne were already talking about the band and the next day’s concert. I was enchanted. Being in a room, dancing to these songs was like stepping back into 1995. It was wonderful. It was what I always imagined happened in England, although I know it probably never really did. It was more like what happened in Los Angeles, back in the ’90s, a quick drive down the 10 freeway from where I grew up.

A rarely remarked upon aspect of Los Angeles is the heavy Anglophilic strain that runs through it. From when the Byrds added the Y, to Rodney Bigenheimer and his English Disco, to the Paisley Underground of the early ’80s, people in the city have looked to England. This was where Depeche Mode and the Cure had their biggest fanbases, and where Morrissey fled to when he was banished from his home country. Even the Sunset Strip glam bands were warmed-over Sweet. This was where the Mod revival never died and where 2-Tone became third-wave ska (sorry about that one). This was where the US home of the Britpop scene was in the mid-to-late ’90s, centered on a club called Café Bleu (named after a Style Council song, for Christ’s sake). Bands like Kenickie played there (so did the Bluetones and Sleeper and others, but Kenickie was and is the important one and everybody knows that), and where we danced to Pulp and Ride and Supergrass, and the Mods danced to Motown and Stax. It was a fantasy, and a fetishization of generations of pop culture that didn’t have a lot of overlap in the first place. It was a little better than eating scones and talking about the Queen, but it wasn’t really all that different.

When I was 18, someone who had recently come back from England told me that his friend there (who was, apparently, the singer from theatrical post-Britpop band David Devant and his Spirit Wife, though this has never been confirmed) talked about how everyone in the UK hated American Britpop kids. Whether true or not, he was probably right because, well, everybody hates a tourist, but to those of us who cared, what they were doing over there was the most important thing in the world. They were a way to get out of ourselves, to be, in a minor way, a little less America-centric, and, most importantly to a teenager, to pick a side a side that was ours, since the rest of the country didn’t care. Our side was clever and energetic. Our side had Jarvis Cocker. Yours didn’t. You still need to believe in these things when you’re 17, because it should mean everything.

***

It was still light out. Grace Jones and her final costume change had left the stage and a large black curtain was raised. Anticipation built, and people began gently pushing forward, carrying around pints in paper cups, and apologizing constantly, like rom-com understudies for Hugh Grant. But this was metaphorical floppy hair tossing, mostly; heads have gotten shinier, and the hairlines of Pulp fans have been receding for the past ten years.

Phrases written in laser began to appear on the curtain, which either mocked rock cliché (“Make some noise! …I can’t hear you…Exciting stuff”), called back to the band’s hits (“Do you remember the first time? …Well, do you?”) or were non-sequiturs (“Do you want to see a dolphin?”). After a few synth stabs, a robotic voice read the words from the Different Class liner notes: “Please understand. We don’t want no trouble. We just want the right to be different. That’s all.”

While the four neon letters of P-U-L-P began to appear one-by-one, the band played the intro to “Do You Remember the First Time?” The curtain was pulled down, the crowd’s singing almost overwhelmed the sound of the PA, and Jarvis, bearded and wearing the glasses he once shunned, danced like nothing had changed. The rest of the band, looking these days more like art teachers than art students, sounded perfect. They weren’t going through the motions, and this wasn’t just for a payday, like the last few years of Pixies shows have been. They were enjoying it.

The set was very Different Class-heavy (as it should be, few bands have made an album as good), and only one non-album song was played (“Mile End,” because it was a London show). They played the hits, and when the hits are this good, there’s very little to complain about; I did, a little, but I had to, on principle. Every kick was cheered; every chorus was shouted to the back of the field. Between the songs, there were small reminders, like discussing how important the student protests are because the band wouldn’t exist without them, of how Pulp have always been a band that has subtly, or not so subtly, exposed class boundaries and urged revenge on those.

Finally, around an hour and half later, “Common People.” With some righteous anger shaking his voice, Jarvis pointed out how on one side of the festival was Hyde Park Speaker’s Corner, a free speech area that Marx, Orwell, and Marcus Garvey once used for public debate, and One Hyde Park on the other, a building “you need to be a billionaire” to live in. “So fuck ‘em.” While it still seems strange that a song this angry, this vicious, a song that spares no one, neither the posh girl nor the working class lad, nor for that matter the narrator or the listener, could have ever become a huge hit (the greatest #2 song in pop history) or a defining song of a generation, it did. It still bites, and it’s still rapturous. While the billionaires might still be our enemy, at that moment, everyone else was on the right side.

Marlow Riley is a writer and low-level media employee living in Brooklyn. On the rare occasions he can remember his password, he is on Twitter.

Photos of Pulp by aurélien. from Flickr.