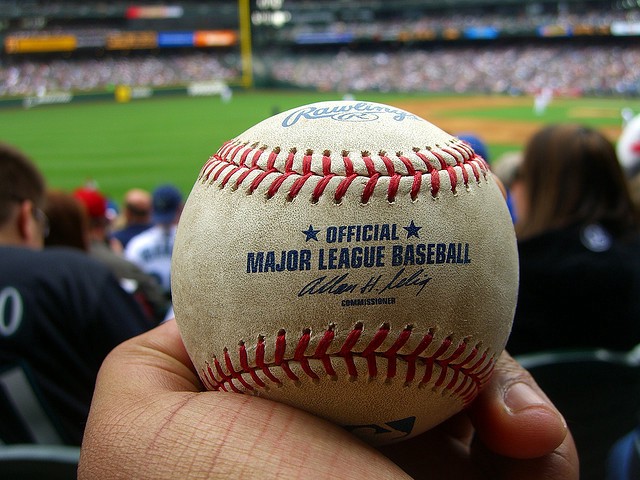

Baseball Fans And The Ball In The Stands

by Herschel Farbman

If the rule is written somewhere, no one has ever read it. Nonetheless, no one disputes it: when a ball goes into the stands at a professional baseball game, it belongs to the fan who gets it. When the ball is the one that was hit to break a record, the fan has won the lottery. The prize can be as high as 3 million dollars (see the ball Mark McGwire hit to break Roger Maris’ single season home run record). The ball that Derek Jeter hit out of the park July 9 for his 3000th hit would have fetched a more modest but still decent sum on the open market — upwards of $200,000 is the estimate of Derek Jeter’s personal memorabilia mule.

So it was certainly notable that Christian Lopez, the cell phone salesman into whose hands the Jeter ball fell, didn’t cash in. Instead, in a touching display of just the kind of generosity big business banks on, he “returned” the ball to a bazillionaire to whom it had never belonged. “Mr. Jeter deserved it,” he said. In exchange, some season tickets and signed bats trickled down, along with many a pat on the head from the press — enough so that no one could say that goodness doesn’t pay, but not what the ball is actually worth. Jay-Z, who was in attendance, just shook his head: “He’s a better man than me.”

The Jeter/Lopez story has been widely covered, but it has been overshadowed — or at least darkly shadowed — by another ball-in-the-stands story: two days before Jeter got his 3000th hit, firefighter Shannon Stone fell to his death at a Texas Rangers game trying to catch a ball tossed to him by Josh Hamilton. Of course, this was all, as Hamilton’s teammate Michael Young was eager to insist, “just an accident.” That it was not, however, an accident of the completely random kind was confirmed four days later, at the MLB All-Star Home Run Derby in Phoenix, when Keith Carmickle, who had already caught three balls, almost fell from the right-center field stands trying to catch a Prince Fielder bomb (Carmickle’s brother and a friend managed to grab a limb apiece as he tumbled over the railing). Such accidents are, as Cardinals right fielder Lance Berkman said of the standard practice of tossing balls into the stands — in response to a question about whether the practice should be eliminated after the Hamilton/Stone disaster — “part of the game.”

Part of the game of baseball, that is, in which the stands play a special role. In no other American sport does the flight of a ball “out of the park,” into the stands, ever count as a point (it does count in cricket, the least American of sports). Indeed, many baseball fans bring a glove to the game, in hopes of getting a chance to make a play. Of course, most fan plays come on foul balls, as home runs are relatively few. But, though the crowd may groan — or yawn — there’s a distant echo of the home run in every foul ball hit into the stands. It’s still a ball over the wall.

The wall that separates the crowd from the field — the inner wall of the double enclosure of the field — is the most important feature of any baseball stadium. No one thinks too much about what that wall looks like at a football game, as it comes into play only after the play is dead (when a player jumps into the crowd to celebrate a touchdown, for example). But thinking of his or her favorite stadium, the baseball fan thinks of that inner wall, and — with iconic fields like Fenway Park in mind — baseball stadium architects look hard for an edge in its design. It’s the outfield sections of the wall, over which home runs travel, that matter most, but the wall is a continuum, broken only when the bullpen door opens to let a relief pitcher enter the game. The outfield sections communicate to the whole a charge that can be felt whenever the wall is crossed — in the little frisson that comes even when a weak foul ball flares into the grandstand, or when a friendly player tosses the ball into the first row.

The thrill would still be there if the fan who makes a play at a pro baseball game didn’t get to keep the ball, but it wouldn’t be the same. Possession confirms the magic of the passage of the ball over the wall. It isn’t quite like this anywhere else: send a ball into your neighbor’s yard, and it remains yours, even if your neighbor is Osama bin Laden (in giving neighborhood kids money for the balls they kicked into his compound, bin Laden recognized the spirit of this law, even as he violated the letter), but send a ball over the wall at a pro baseball game and it belongs to the crowd. Such a transference of ownership happens in hockey, too, when a puck goes over the glass, but the investments in that puck are not the same — the most a hockey team can get for sending the puck into the stands is a delay of game penalty. It can sometimes happen at a football game, when a player gives a fan a ball, but it’s more the exception than the rule there, and the generous player has to pay a fine to the league for making the gift. It never happens at a basketball game.

The magic of the relationship between the baseball field and its beyond is such as to invite the grandest mythical and metaphorical projections. For the orthodox myth of the field of dreams, see pretty much anything written about baseball by A. Bartlett Giamatti, scholar of pastoral, former commissioner, and ideologist-in-chief of the game (or just see the Kevin Costner movie). Meanwhile, the literature of baseball heresy still awaits its great text. Catching sure-handedly all that is essentially urban about the game, Don DeLillo’s Underworld, which tracks the destiny of a baseball hit into the stands, is certainly a big time, big league text, but even the sharp twists it gives to the corndog “taste of Eden” orthodoxy don’t shake the work all the way free of it.

In “The Triumph of Death,” the bravura opening section of Underworld, a puking Jackie Gleason embodies convincingly an unsentimental point of view, but the smoke thrown up by the whole scene is certainly in DeLillo’s own eyes as he watches Cotter Martin, a character he has created to fill a gap in the historical record, collect Bobby Thomson’s iconic home run ball — the projectile in question in the “shot heard round the world.” According to DeLillo’s grand, historical scheme, this “shot” is really two: an early Soviet test of a nuclear bomb echoes it. J. Edgar Hoover, who’s at the game along with Gleason and Frank Sinatra, receives news of the test just as Ralph Branca, whose high inside fastball Thomson will smash, gets up in the Dodger bullpen. Ironic though it is, this doubling of Thomson’s shot amplifies it, resulting in a very impressive bang — the sound is that of the Cold War beginning and the preceding age coming to an end. It does not produce any thinning of the smoke that hovers over the classic ballgame. The Cold War light that DeLillo summons to the game is supposed to be chilling, but DeLillo’s irony is a bit too good. In the end, it only reheats the standard myth, in which a baseball is a little fragment of a world before a fall.

If a baseball were really that, though, fans would not care about the game in the way they actually do. This is hardball, after all: what keeps the fan watching is sheer anxiety over the volatility of the unscripted event itself. The fan obsessively studies statistics and assesses probabilities — and consumes and traffics in all the myths — because he or she lives every day in awful (and exquisite) uncertainty about how the next game (every little bit of it) will go. MLB is absolutely right to fear more than anything a repetition of the Black Sox scandal of 1919, in which games were fixed (though Pete Rose’s lifetime suspension from the game for gambling on it may be a little harsh), as such a disaster would affect precisely what the fan most cares about: not the fairness of the game, exactly, but its unpredictability.

One name for the object of the fan’s most intense interest is “history” (little “h”). Minor though it may be, a game is itself an authentic historical event. No big explosions are necessary. What Shannon Stone was reaching for July 7 was less a token of paradise than a little piece of history — not a piece you could sell for much, if anything, at a memorabilia show (it was only a foul ball, picked up and tossed into the stands by the left fielder, not a significant hit), but a piece of history nonetheless. To call such an object a fetish (and “piece of history” a cliché) wouldn’t be entirely false. But while it was suspended in the zone between Hamilton and Stone, between field and crowd, where all the energies of big time baseball gather, that ball was an indeterminate thing, carrying all the surprise of the actual event.

The hot, highly fetishized commodity the fan in the stands walks away with when he walks away with a more obviously “historic” ball forms itself around this spinning, hard core. That doesn’t mean that Christian Lopez was not silly to refuse to treat the record-breaking ball he caught as a commodity. It only means going for the ball was not, in the first place, a question of exchange and all the calculations that that entails. The ball was there, up for grabs. Like Stone, Christian Lopez just went for it.

The locus classicus of this primal and utterly ordinary response to the baseball event, in all its raw volatility, is the infamous Steve Bartman incident. Thinking of Stone and Lopez (and Carmickle), I can’t help but flash on it. On October 14, 2003, Bartman, a Cubs diehard seated by the rail along the left field line, interfered with a foul ball that Moisés Alou might have caught for the final out of what instead became a disastrous inning for the Chicago Cubs in game 6 of the NLCS. The Cubs lost the game, from which Bartman had to be escorted by a small army of security guards, and went on to lose the series. Bartman has been reviled in Chicago ever since, and lives more or less in hiding. But the ball was right there, in that wild border zone where it was no more Alou’s than Bartman’s. Alou reached for it. Bartman reached, too.

Bartman didn’t make the catch. The ball bounced away into the stands, and someone else walked away with the six figures that Grant DePorter, managing partner of Harry Caray’s Restaurant, paid for it. On February 26, 2004, with great fanfare, the ball was exploded at the Chicago restaurant, which would have seemed to have been the end of the story, except that a year later, the remains of the ball were soaked in beer and boiled to generate steam, which was captured and used in the preparation of a pasta sauce. And so, through a process of sacrifice and communion, the ball was consecrated entirely to the hot air of baseball’s big myth.

Such a rite was inevitable; the raw event had been unbearable. But I agree with the writer of this 2004 article: it would have been better had the ball somehow ended up with Bartman. Were there a baseball god, the story would have ended like this: a Christian Lopez figure would have miraculously materialized in Chicago in the winter of 2003–4 — but upside down, cruel, with pockets full of money — to buy up the cursed ball and “return” it, with all the apologies under the sun, to Bartman, who did everything and nothing to earn it.

Herschel Farbman teaches English and French at UC,Irvine.

Photo by permanently scatterbrained.