A Q&A With Jon Langford Of The Mekons

A Q&A With Jon Langford Of The Mekons

by D.E. Rasso

It’s likely that you either love the Mekons, or you haven’t heard of them at all. Formed as a punk band in Leeds in 1977, the sprawling lineup has remained more or less the same since the mid-’80s. Their sound spans multiple genres, among them American rock and roll and roots music. (They are, in fact, credited with producing the first alt-country album.) If you go to a Mekons show, expect to see some incredibly ardent fans, every music critic in town, and an energetic performance from all on stage.

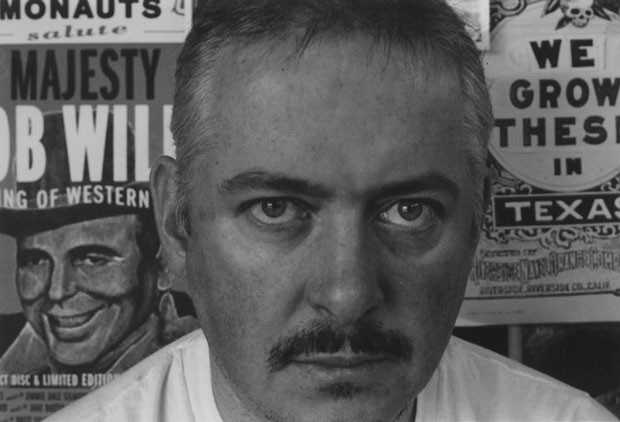

I had the opportunity to interview Mekons cofounder and guitarist/vocalist Jon Langford while he was on a family vacation in the hinterlands of Michigan. We discussed the history and evolution of the band, the sometimes frustrating process of recording an album, touring, meeting one’s heroes, and the new Mekons album, Ancient and Modern, due out in September.

D.E. Rasso: Is it true that Lester Bangs said that you were better than the Beatles or is that apocryphal?

Jon Langford: He did say that, he did say that. I’m sure it was partially tongue in cheek. Who knows, he said a lot of things.

And Jonathan Franzen gave you quite a nice blurb [for your new album].

Jonathan Franzen is a very nice man. I like his books; they’re very good. He’s been very supportive.

We’re very flattered by a lot of the people who say that they like what we do. But the whole thing about saying there was something “pure” about what the Mekons have done, this whole “authentic” thing, there is a thread that goes back to what our initial kind of manifesto was in 1977. And what the kind of groundswell of feeling was at that time about what a band should and shouldn’t be, you know.

And it was a collective thing that was going off all across the country. It wasn’t something we were just like inventing ourselves. There were just a lot of people who were just sick of it, of how boring the music industry was. I mean, God knows it’s even more boring now…

Well, I was going to ask, do you think there’s even a similar movement in music today?

I can’t say. I’m an old fart now. I really am, a 50-year-old guy, so I fucking haven’t got a clue what kids are doing. I don’t know if it feels the same to them. I just know it was all-consuming and exciting and amazing and the possibilities seemed limitless to me when Mekons formed. And I was 19 years old. And I still hold some of that kind of idealism.

But there was always a lot of humor with the Mekons as well, this kind of barbed edge to it and a kind of Stalinist edge to it… and one week we’d be trying to write, you know, songs to change the world and it’s like socialist anthems and then the next week it was like, “This is a lot of shit.” The thing about the Mekons is we were always very aware of what we didn’t want to do. And as things came up we could have a big list and scratch off all the things we didn’t want to do. And our manifesto was a list of things we didn’t want to do. We never really did say what we did want to do.

What were some of the things on the manifesto?

We will only be a support band. We will never have our photographs taken. We will not make a record. We will not have our names printed, or an address. It all came crashing down. Reality evolved. But the important things were the things we didn’t write down: that we thought a band didn’t have to exist within the structure and rules of the music industry. A band could be whatever you wanted it to be.

That’s what [the Mekons have] turned into: this collective of people who just choose to get together every now and then, and do some things for their own amusement. No pandering. I don’t think we’ve been at a point in our career when we thought, “Let’s do something like that, because that was successful.” It was a real revulsion against that. It was like we tried to shoot ourselves in the foot at every possible point… when things started going quite well with respect to the business [aspect of the band], we would deliberately dismantle that which was working.

What if one of the members of the band were to say, “You know what? I don’t have time to do this anymore,” or, “I think I need to spend some time working on something else,” what would happen?

Well, people have and people do. You know?

But you guys have had a lot of the same lineup for a long time.

We’ll usually just say, “Well, how much time do you fucking need?” On these tours, we only take up about a month of anyone’s year. I don’t think anyone’s really complaining about the workload.

I think there’s this gravity, as well, that pulls us back together. If we haven’t seen each other for a while, it feels odd. It’s a very old friendship between people in the band.

It was like we tried to shoot ourselves in the foot at every possible point… when things started going quite well with respect to the business [aspect of the band], we would deliberately dismantle that which was working.

Is there any sort of Mekons manifesto in 2011?

Not that you’d write down. But I think there’s a cloud of mass delusion that this is actually worth doing. [laughs]

I think sometimes, a lot of times in the Mekons’ career, the motivation, more than anything else, seemed to be like a big fuck-off to the world: “I will not be ground down into dust.”

Clearly, the longevity of the band must have something to do with that.

Yeah, I think it’s a sort of persistence. It hasn’t been financially rewarding for anyone.

It’s been a couple of years since the last Mekons album. What was the catalyst for Ancient & Modern?

We did Natural in 2007 and I think pretty much immediately after that we started trying to record another album, but we’re very spread out across the world and the older people get the more commitments they have outside of the band. It’s not the be-all and end-all of our lives.

You recorded it in the UK?

It was recorded kinda all over. Basically, Tom [Greenhalgh, Mekons member and cofounder] has a job and four kids, and he lives in a thatched cottage in the countryside in the southwest of England, and we were trying to work out a way of recording somewhere while we were on our tour, so it wouldn’t be too detrimental for him, so we ended up renting a house and bringing a mobile studio in. Rico [Bell, Mekons member]’s son Walter came and recorded — he works with Lu [Edmonds] in Public Image Limited, he does their sound — so he basically set the whole thing up in the house, which was quite odd. It was obviously some sort of sex-obsessed bachelor’s pad, kind of arty but lots of paintings of nude women on the walls and stuff.

How did the female members of the band feel about that?

Thought it was ridiculous [laughs]. It was kind of creepy. It was weird… But it was also within walking distance from Tom’s house. So that was kind of useful, and he could go to work in the daytime and come over in the evenings and do some recording late at night, so it was kind of a 24-hour recording thing going on, with Sally [Timms, Mekons member] coming down the stairs in the middle of the night and telling us to shut up because she was sleeping.

So at some point in the distant past did you imagine that being a musician was going to be a full-time job?

No, never really. It has become one at times and then that’s when it’s been the worst experience, to be quite honest.

Yet you guys put a lot of energy into touring and into your live shows. Do you genuinely enjoy being up on stage?

I’d have to say we do. I think people enjoy it, but it has to be the right circumstances. We’ve had horrible times on stage, just even recently.

Really?

[Sometimes] you end up doing a gig with couple of vital people missing because they’ve got other things booked, and then it’s really difficult.

But I’ve seen the Mekons and the Waco Brothers dozens of times, probably, over the past 20 years or so. I have to say that the energy has always been really fantastic, both onstage, and I feel like your fans have a particularly special energy. My perspective is from being in New York, where audiences, I think, are blasé in general; yet, the audiences at Mekons shows, I think, are pretty energetic and excited to be there.

There’s different sorts of energy, as well. I mean, we played The Bell House [in Brooklyn] a couple of years ago. We had a great night. Then the next night, we played a club in Manhattan, and we played a lot later, and it was just a very different atmosphere. It was very strange. Suddenly, it was like we went from Woodstock to Altamont.

The Bell House is a great place to see shows.

I performed there with the Waco Brothers, with Skull Orchard, and with the Mekons, and had a great time every time. I really like that room. The people there are really nice; that helps. When a club’s just starting out, it seems like they go the extra mile, and they’re still enthusiastic. There’s clubs in New York I’ve played at, where I’ve actually said to the people, “You should stop doing this. You’re obviously not having a very good time.”

What cities, or particular locations, have you liked performing in the most?

We’ve enjoyed playing Zurich lately. We’ve done some great shows in Zurich the last year. We went back again in June and did two shows. It has been really surprising some people, to go somewhere and see people be really interested.

Do the Swiss just get you better than Americans do?

It was just that we hadn’t been to Switzerland for about eight years, and it was like this grand homecoming. I think absence makes the heart grow fonder. We should take eight-year breaks from all of our regular markets.

Yeah. Maybe pretend to break up and then get back together, and then…

That has been our biggest mistake, never breaking up.

I think the repartee that you guys have onstage with each other, if it’s real —

What do you mean? We wouldn’t be able to say all those things to each other if it wasn’t real. Mekons has been real, I can tell you.

Yes, I know, um [frantic apologetic mumblings]… What I meant was to emphasize that this is part of the reason why I was so enthusiastic about being able to talk to you. Because of the fact that it’s one of those things where you often don’t want to end up meeting people that you idolize, because you’re worried that they’re going to end up being disappointing. But I hoped that wouldn’t be the case.

You know what? That’s 50% true. In my experience, I have heroes, and some I’ve met and been awfully disappointed, and just thought they were horrible. Then others I’ve met, and they’ve been amazing.

You met Johnny Cash, right? A number of years ago.

Yes. He was not a disappointment and not what I imagined. Nothing like the fuckin’ I Walk the Line myth, the Hollywood crap. Nothing like that at all. Very funny, humble, gentle guy.

Who else have you met that you’ve really enjoyed meeting?

Well, I’ve got some people I really like whom I’ve actually had the pleasure of working with. I worked with Johnny Cash a bit on that record we made in the ’80s. I made a record with Kevin Coyne, who’s a singer/songwriter from England, who I was enamored with from a young age. A notoriously difficult guy, someone that I was told would be horrible to meet. I was scared. When I met him, he was great. We got on, we had some fun, and made an album together; had a really nice time.

And also, John Cale. Lovely. I met him. Everyone warned me that that was going to be a nightmare, so I steered clear.

Perhaps it’s just that you just bring out the best in everyone else.

Do you think so? I try. [Birds chirping in the background]

You even bring out the birds.

Yeah, I’m standing in a kind of nature preserve-y area of some sort.

There has always been a hatred in the Mekons of self-righteousness and purity, which are [characterizations] that people have cast upon us. We’re just a group of people who choose to work together.

So the new album.

Yes. We mixed it with Ian Caple, who mixed [Mekons albums] Rock ’n’ Roll and Honky-Tonkin’.

It’s funny, I was thinking “Space In Your Face,” off the new album, has a rich, full sound, sort of similar to Rock ’n’ Roll.

Working with Ian, he really understands where we were coming from. It started off as just a really light little tune, played on acoustic guitars, in a cottage somewhere in Devon. Then we took it back to Chicago and just kept amping it up, and amping it up. … But [often, the contemporary recording process can be] a terrible, terrible process that we’ve come up with. Really idiotic, expensive, and wasteful; but the end result I’m satisfied with. I think.

Wait — is recording an album worse than touring, than performing live?

I think it’s more stressful. There are moments that I really enjoy that feeling of just being in the studio, when you’re writing and ideas are really flowing, and it’s very immediate. But there are also periods of waiting around, and fracturing things, and I don’t enjoy it that much.

But we were pretty much on the same page with this record. It was a kind of pragmatism [where we accepted that] not everyone’s going to be there all the time. Usually with the Mekons, everyone has to be in the room when everything happens; with this, people could do their bits and send them in. We tried to utilize the miracle of the Internet. But it’s not a labor-saving device; really, it just makes for more lack of sleep.

But when we came to mix the stuff, we were actually recording and singing bits on it while we were mixing it; and radically editing the songs, losing big chunks of things, and adding other things. I don’t know, it just never stopped evolving. I like the idea of making an album where you go for a week, and then end up with a finished album. This was like, two years of thinking about something.

So has technology made it more difficult rather than making it easier?

It’s 50/50, you know. I think if you use it creatively, it’s fantastic. There are amazing tools but it can also become a trap, you know. You can just get sucked into it, and then there’s no reason to ever finish anything. There were a lot of reasons for not being able to finish this album quickly.

A lot of it is just the logistics of — oh, a beautiful red cardinal just flew by, looked like a bloody great parrot, fantastic — so yeah, that’s kind of the rules of the Mekons: There are no rules…. why shouldn’t we spend two and a half years making an album from different points in the world, you know? There’s no reason not to. It’s like we mixed it and left it for a little while and didn’t listen to it. Before we sequenced it and Lu mastered it in London….

And mastering is really important but it’s a process I really hate attending. I don’t understand the magic that goes on there. But then getting it back with all the tracks in order, all kind of tweaked so they were all the same level and suddenly it was like, Wow, now it’s an album. Now it’s an album I can just sit and listen to. I have little favorite bits and I’m not constantly remixing it in my head. I hope it’s like that for everyone else as well.

What are you envisioning for the next album?

Oh, to go into a room and emerge a week later with a finished album. Just to record a lot of stuff and then edit it down and decide on something else. I just want something a bit more immediate. This was actually anything but immediate and it found it took up a lot more of my brain than I wanted it to for a long time… It’s creative and frustrating at the same time.

This new record is on your own label, Sin Records, that you’ve revived, right?

Yeah, it’s the label we worked with, the label we created when we had a manufacturing and distribution deal with Red Rhino in England. It lasted up to the point where we did three or four records with it, then we went to Cooking Vinyl…[eventually we ended up with] A&M; in the States, which was this strange slide into professional-ness, which none of us were really that interested in.

We had a very safe harbor for 15 years with Touch and Go, who picked us up and said, “You’re kind of interesting. Let’s see if we can work together.” It was just this seamless, easy, great relationship for 15 years, with people we really trusted, and without the danger of somebody just trying to scam us. But then they stopped putting records out. [Reviving Sin Records] seemed an obvious thing to do, to try and find someone who would do a manufacturing and distribution thing, but to have our own label again.

Bloodshot Records are close at hand in Chicago and I had worked with them a lot. They didn’t need a lot of explaining about what the Mekons were about. We thought if we went with another label, a proper label, it would just end in tears, because they wouldn’t understand what the band does. It’s pretty hard to explain the way we work, in our way, our level of ambition, et cetera, et cetera.

What is your level of ambition?

Zero. So, with [Bloodshot] knowing so much about the band, we thought that relaunching the Sin label might be a cool thing.

Then do you prefer the DIY approach to music?

During the development of punk rock it was just that, just putting aside the notion of dealing with the proper music business. I mean, we did deal with the proper music business at various times…

With A&M;?

A&M;, and Virgin before them. They weren’t really happy experiences, to be quite honest, although in both those situations, I think we made really good records. But we got kicked off those labels for making the records we wanted to make and not “polishing the turd,” as we would call it.

It was interesting to be on major labels, but also completely soul-destroying at the same time. I think we learned a lot. Creatively, it wasn’t necessarily that bad; but personally and financially, it was pretty depressing. I never really wanted to make the band a career. We bent over backwards to try and work out what was going on, and be good employees… until we gave up.

When you started out in Leeds, you were surrounded by this punk ethos, and a lot of bands that are also quite well known. Do you feel like now, 30-plus years later, you’re still subscribing to that same ethos? Do you feel like you have been able make music without making too many compromises?

Oh, I think we’ve made loads of compromises, willing and unwilling. But we’ve experimented, and asked ourselves, “Why are we doing this exactly? What if we do this?” I think that’s the case with the major labels, was why we were being pure. There has always been a hatred in the Mekons of self-righteousness and purity, which are [characterizations] that people have cast upon us. We’re just a group of people who choose to work together.

Wait, so are you saying that you don’t like the idea that you’re characterized as being authentic?

No, not at all, I think it’s a load of bullshit. I’m no more pure than, I don’t know, custard.

There is a certain amount of veneration that the Mekons get from fans and from critics alike.

You know, that’s not the reason why we’re in it, you know. We’re quite uncomfortable with that.

So, with Ancient & Modern, what was the idea behind it?

The original working title was A Hundred Years Ago. The 1911–2011 thing was a very conscious decision, to talk about the last hundred years, and what was actually going on at that point in history just before the First World War. There’s definitely a theme, you know, even if it’s loose and tangential.

It’s a concept album?

It’s a concept album, yes. It does have a concept. … I think that most of our records have a concept behind them, so…

Is it actually going to be on vinyl as well as CD?

Yeah.

But not 78.

[Laughs.] Actually, it’s all wax cylinder.

That would have been awesome, actually.

Yeah, that would have been good. We would have sold even fewer records than before, and that’s always appealing to us.

Does each of the songs have a particular connection to an event that occurred a hundred years ago?

Definitely. “Space In Your Face” actually talks about the bombing of the LA Times. It was a time of domestic terrorism, huge corruption, and witch trials… so there are all of these similarities [to today]. It’s almost like that period leading up to the First World War was like the end of human history as it had been. And what we’ve lived through, from the 20th century ’til today — it’s just the modern world, you know, and all of its glory and destruction.

Now there’s a train going past. Bird noises have been interrupted by train noises now. I’m having a very American moment.

D.E. Rasso is a writer and blogger who has spoken inexpertly on the topics of music criticism, the future of publishing, Internet impostors and weird things from dollar stores.

This conversation took place by phone and has been condensed.