Julie Taymor Was Always The Wrong Superhero For 'Spider-Man'

Without vanity a writer’s work is tepid, and he must accept his vanity as part of his stock in trade and live with it as one of the hazards of his profession. — Moss Hart, Act One

On Saturday, in downtown Los Angeles, Julie Taymor sat down with Roger Copeland for the much-anticipated closing keynote presentation of the Theater Communications Group’s annual conference, before an audience of a thousand or so colleagues. Copeland is a big, charming, rambunctious man with about the biggest, bobbingest head you ever saw, wearing very thick glasses and, I think, no socks. He’s a professor of theater and dance at Oberlin College, Taymor’s alma mater, who has written extensively and admiringly of her work.

If you’re involved in the sort of Theater with a capital T that is “avant-garde” or “serious,” TCG is the place to go in search of fellowships, grants and jobs. Taymor made her bones in this insular, rarefied environment, but later went out and took the greater world by storm; she is the first woman to win a Tony Award for directing, for the blockbuster stage version of The Lion King, and she’s directed several Hollywood movies. But Taymor has lost none of her cred with this group, because her approach has remained resolutely avant-garde, highbrow and scholarly. Eager to welcome her back into the fold, Saturday’s crowd of BFFs could barely contain their standing ovations. “We are her family,” said board member Philip Himberg in his introduction.

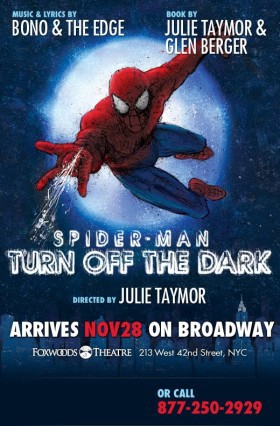

Taymor’s poise and delicacy of movement were thrown into sharp contrast by Copeland’s massive presence across from her onstage. She wore indigo jeans, a rather piratical white shirt and a slightly shrunken, overstitched dark buff jacket of complicated design. Never in a million years would you guess that this slim, elegant woman is near sixty. But for all her grace and ever-perfect hair and aura of general expensiveness, there’s a certain tension in Taymor, a wariness that was visible throughout the three days of the conference. And no wonder, given the fracas of her dismissal in March from the Broadway musical, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, that opened last week to tepid reviews after nine years in production.

So, did the trusty Copeland ask Taymor about Spider-Man? He did, though he danced around the subject like crazy, using phrases like “I hope you don’t hate me for starting with this,” and “the $64,000 question,” and “… an ordeal that played out in public, so that even Anthony Weiner must have been saying, ‘at least I didn’t have to go through THAT’.” Indeed, Copeland’s actual question was ultimately lost to me in all the bobbing and weaving.

But did Taymor finally provide her version of events to a curious and sympathetic public? Not even. There’s a good reason why not, I suspect; one to do not so much with the talented director’s famed self-consequence as with the questions of cold, hard cash that so often lie behind the plying of the arts trades at their highest reaches, where incomprehensibly large sums are burned through in search of a mass audience.

Too Big To Not Fail

The first, and worst, catastrophe to befall Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark came in October of 2005. Several very prominent artists had been assembled by the producers, including Bono and The Edge of U2 as well as Taymor, so contracts had already taken years to negotiate, what with the principals’ conflicting work schedules and various internal difficulties at Marvel Entertainment; the delineation of responsibilities, royalties, limits of control and all the rights issues had involved rafts of lawyers in the thorniest and most protracted wrangles, but all had at last been set right, and Taymor and Bono had signed. Then the producers went along to The Edge’s Tribeca apartment with the contract. And just as The Edge was about to set pen to paper, right then and there, producer Tony Adams collapsed with a stroke. He died two days later. Only 52 years old, Adams was the veteran of many, many successes including Blake Edwards’s Pink Panther films, 10, and both the filmed and stage versions of Victor/Victoria.

It was Adams, along with his partner, show-biz lawyer David Garfinkle, who had first secured the stage rights to “Spider-Man” from Marvel and brought U2 on board for the music. Garfinkle had none of Adams’s direct experience as a producer, but seems by all informed accounts to be a smart and good guy, a talented negotiator and a lifelong theater freak who had raised a lot of money in his hometown of Chicago for the show; his father was reported to have been the first investor. (Far and away the best précis of the genesis of Spider-Man’s troubles on Broadway is to be found in this profile of Garfinkle by David Bernstein for Chicago Magazine.)

It was never going to be anything but a bumpy ride. From the beginning, the producers had envisioned a gigantic show with a gigantic budget, and they had enormous, glacially slow-moving forces to contend with from the first minute: the media conglomerates, Sony and Marvel; the stars of U2, who were out on tour when most composers would have been glued to the theater; a huge gang of rich investors, who by the end had ponied up a reported $70 million, each with his own worries and demands. And finally, there was the notoriously uncompromising Taymor, well known to be willing to sacrifice any amount of money to realizing her vision. In one of many articles sounding the same note, Michael Riedel reported on Spider-Man’s troubles in the Post in August 2009: “’You’ve got to be on top of her all the time,’ says a person who worked with her on ‘The Lion King.’ ‘She’ll spend days and days on one minute of stage time. It will be a brilliant minute, but it’s expensive.’”

After Adams’s death the production continued to inch forward, but the difficulties snowballed. Permits for rebuilding the Foxwoods Theatre were complicated by its landmark status; Evan Rachel Wood and Alan Cumming had to leave for other projects; people got hurt in rehearsal, some of them quite seriously; the economy crashed and burned.

Money Makes the World Go Around

But the real mess began when Spider-Man finally went into previews, and it emerged that though the sets and costumes were gorgeous, and all the stagecraft spectacular, the show utterly lacked a story. The incoherently repurposed mythological/comic-book character of Arachne came in for the worst drubbing, particularly a song (since dropped) called “Deeply Furious”, that was something to do with giant spider-girls having a shoe fetish. Frantic attempts were made to retool the production, and tempers frayed as the result of the bad notices; Taymor was asked to leave her role as director in March.

Whatever happened, Taymor still has an ownership stake in the production — an amount yet to be determined or litigated, perhaps — an an unknown sum that might or might not come to be very large. And so Taymor, the show’s producers, Bono and The Edge have all been cagey in their public comments about the trainwreck of Spider-Man.

That is to say, if Spider-Man turns out to be a hit after all, there will be lots and lots more money to squabble over than just the $200,000 to $300,000 in unpaid wages that Taymor’s union filed suit for on her behalf last week.

Though the press has been quiet on this aspect of the matter, the Daily Mail managed a few conjectures from “a source”:

As [Taymor is] the musical’s creator, director, mask designer and one of its two script-writers, negotiations over ‘who owns what material, and how the royalties and future development of the show in productions around the world will be worked out,’ are very delicate […] Apparently, both sides are keen to prevent having to fire her outright, which would almost certainly result in a lengthy and embarrassing court battle.

To give an idea of the potential of a super-smash-hit musical, The Lion King, which catapulted Taymor to superduperstardom, has grossed over $4.5 billion so far. Even the tiniest of royalties, at that rate of exchange, is going to add up to a boffo amount of coin.

The only comment Taymor made regarding her stake in the future of Spider-Man during last week’s conference was a wry, throwaway one near the end: “I’m lucky because I’ve had one hit… maybe two, we’ll see,” which got a huge laugh from the audience.

If not, then the show’s producers and investors, Taymor, Bono and Edge, or The Edge, whatever (his name is David Evans! — and Bono’s name is Paul Hewson, and I can’t believe we have to call two grown men these ridiculous names) will perhaps remain just gigantically rich, instead of gigantically-plus-some-huge-amount rich.

The two U2 frontmen have long been known to be all about the money. Both musicians have come under increasing fire in their native Ireland for moving their music publishing business out of that country in 2006, in an effort to evade the already insanely favorable income tax for artists (who get their first $650,000 or so of income tax-free every year). The Edge’s memorable comment at that time was, “Of course we’re trying to be tax-efficient.” Author Marina Hyde’s equally memorable response was to observe that Bono, who has a house in Ireland, seems perfectly happy to be “driving around on roads paid for by teachers, and nurses and plumbers — the very people he’d appeal to for donations when an African village needed a well. Or indeed, a road.”

Bono admitted to Patrick Healy in the Times last week that he did not put any of his own money into Spider-Man, though The Tax-Efficient Edge did contribute an undisclosed amount (to “underscore his commitment,” apparently).

Taymor turned up for the Spider-Man premiere last week and distributed uncomfortable-looking hugs and smiles for the camera. Now that Cui Bono has released a few remarks about how much he “misses Julie” and so on, it looks quite a lot like there are legal and contractual disputes still unresolved. Money disputes. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that at these altitudes of the art world, the money part is way more important than the art.

The Superhero Part

Taymor’s most successful works, such as The Lion King, are based on simple, literal stories already fully fleshed out, like a readymade armature that can be adapted and clothed to suit her purposes. As a visualist, she is every bit the genius and visionary one has so often heard praised over the years; everyone seems to agree on that. Her works are crafted with such a teeming, multivalent sensuality and in such meticulous detail that they practically induce synesthesia; sights so beautiful you can nearly taste them.

The short film Fool’s Fire is a perfect decoction of Taymor’s talents. She adapted the script herself from a wicked little story of Edgar Allen Poe’s called “Hop-Frog” for an American Playhouse production that appeared on PBS in 1992. It’s a revenge tale along the lines of “The Cask of Amontillado,” but it’s much simpler, like a fairytale really. Here she cast the staggeringly wonderful Michael Anderson as a court jester who socks it to the evil king and his hideous rubber-masked cronies. This story has no moving parts; justice is served up in a fiery ball, that is pretty much it. But it’s beyond gorgeous, and there are some wonderful set pieces, notably a magnificently horrible Trimalchian feast, in the course of which one of the bloated aristocrats explains the preparation of Roast à l’Imperatrice:

Take the pit out of an olive and replace it with an anchovy. Put the olive into a lark, the lark into a quail, into a partridge, the partridge into a pheasant. The pheasant in its turn disappears inside a turkey, and the turkey is stuffed into a suckling pig. Roasted, this will present the quintessence of the culinary art, the masterpiece of gastronomy. But don’t make the mistake of serving it whole, just like that. The gourmand eats only the olive and the anchovy.

The thing is, the world-class ironist Alexandre Dumas was kidding, there, when he wrote this recipe in his Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine, and yet Taymor thought to use it to lampoon a bunch of greedy aristocrats, so it sounds kind of wrong; a joke to stand in for the-thing-joked-about. This is a failure of humor, a misunderstanding of the nature of self-mockery or the generality — the complicity, really — of human failings.

But who cares, because “Fool’s Fire” is so, so lovely. Bowls of soup dashed onto a stone floor take on a freakishly moving, magnificent urgency and scariness. The dwarf princess Trippetta and her beautifully fanning, feathered fingers; the richly mysterious, flickering shadows, the beautiful, tormented face of Hop-Frog as he flees his pursuers, or his shirtless form laboring over the construction of a wooden throne; the cunning, clever lisp with which he pronounces the doom of his enemies. It is 100% enchanting.

She Has Radioactive Blood

There’s a temptation to take Taymor’s famously lofty, self-consciously learned pronouncements as a kind of contempt for “the little people,” or as plain arrogance, but after studying her work and following her around this conference, I came away with a different impression. She seems to me to be the sort of person who, even as an adult, remains a kind of gifted kid, a teacher’s pet, almost — crazy focused on and serious about her work; a person who has spent her whole life working like a maniac on just the one thing that she is very, very good at without a moment’s doubt or pause. She’s almost absurdly secure in her own skin for this reason, and while this has to be an asset in her business, it can also be a fault. A blind spot. You might say that what she’s got is a sort of overconfidence in her own superpowers.

After Spider-Man began previews, it wasn’t long before Taymor took the fall for the bad notices. She turned up at the TED conference last March and gave a talk, the video of which is mysteriously absent from the TED site; requests for an explanation of its removal went unanswered (naturally, it’s super easy to find online anyway). The Q&A; after the TED talk marked the first time Taymor had been asked in public about her troubles with Spider-Man; her ouster was, in the event, just days away. In response to questions about the future of the show, she went into an extremely wacky riff that did not go over at all well with many, including the A.V. Club’s Sean O’Neal, who’d been covering the story throughout. His brief account is called, “Julie Taymor acknowledges Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark problems in typically pretentious way”:

At the TED conference, Taymor humbly said she was “in the crucible and the fire of transformation,” adding that “anyone who creates knows — when it’s not quite there. Where it hasn’t quite become the phoenix or the burnt char. And I am right there.” Piling on the metaphors, she related the production of the musical […] to this one time she went to Indonesia, where she and a friend climbed up between a dead and a live volcano, and her friend disappeared in the smoke and left her there alone:

“It’s very easy to climb up, is it not?” she said. “I am on the precipice looking down into a dead volcano on my left, on the right it is sheer shale. I am in thongs and sarong and no hiking boots. I realize I can’t go back the way I have come. I can’t. So I throw away my camera. I throw away my thongs and I looked at the line straight in front of me. And I got down on all fours like a cat. And I held with my knees to either side of this line in front of me — 30 yards or 30 feet, I don’t know. The wind was massively blowing, and the only way I could get to the other side was to look at the line straight in front of me.””

If you think O’Neal was rough on Taymor, have a look at the pasting she took in the comments on his piece, wherein readers poured out a fusillade of droll commentary (a lot of which focused on who or what was “massively blowing”):

It’s a little painful to see this talented, well-meaning artist raked over the coals in such a way. But Julie Taymor, you cannot be forever explaining how you went to Indonesia to study shadow puppetry, or how you came to be lying hidden under a banyan tree in Bali, nursing a leg wounded by a rock spit from a volcano, because people are going to think it is The Onion. No, not even if it’s all true and you are so super earnest because you care so much and take it all so seriously.

The Sorcerer On Her Island

Taymor’s complicated relationship to the audience became apparent again at the TCG conference screening of The Tempest.

In her introductory remarks, the movie’s producer Lynn Hendee said, “This audience will be the only one we’ve had that understood that The Tempest is a play by William Shakespeare.” (Lord, what yahoos these mortals be!) Later, Taymor made a similar observation, sounding pretty danged sniffy: “People don’t know how to review a Shakespeare film well. They criticize the plot.”

During the Q&A; I asked how those assembled had approached the idea of translating Shakespeare for a popular audience. The movie’s star, Helen Mirren (who’d been kind enough to attend the Q&A; despite having been delayed for three hours at the airport), talked at some length about how much work it took to make “Prospera’s” speeches immediate and comprehensible. To contain the sense, more or less. She credited Taymor with understanding this, and with having the same goal. And it is true that Mirren has that amazing Royal Shakespeare Co. skill of making you understand Shakespeare’s language so effortlessly that you could nearly believe that these dense Elizabethan speeches were all blogged yesterday.

But Taymor rather scoffed at the idea of making particular alterations for a popular audience and said, straight up, “You don’t do Shakespeare to make a lot of money.” We did this “for the canon,” she said; she expressed the hope that the film will be taught in schools.

Seemed like a ballsy thing to be saying in front of the producer of the movie, I thought. Surely at least you should want to make back the $20 million that it cost to make? Because to date, according to Box Office Mojo, this movie has seen only around $350,000 in receipts.

And isn’t it all connected? Because there is no percentage in making stuff for an audience toward whom you feel, if not outright contempt, an absolute, unshakable certainty that you always know better. And then, is there a legitimate distinction to be made between those who attend a filmed version of Shakespeare and those who spend a kajillion dollars to take in a show on Broadway? If you need a mass audience to make the work a success, does this really necessitate “dumbing-down”?

Plus, this production of The Tempest, beautiful as it is, is lacking a great deal from the highbrow or pointy-headed angle. Casting a woman as Prospero in order to show a mother’s protection of a daughter rather than a father’s was reckoned an interesting move by many, and there’s no question that Helen Mirren makes a wonderfully doughty sorcerer. But from a feminist point of view, this decision could not be more disastrous. If Miranda seemed like a MacGuffin or trading card in the original story, she is trebly so here. It’s one thing for Prospero to give Miranda to her next lord and master at the end of the story, and quite another for Prospera to do so; basically she ends by giving her kid back over to the patriarchy that abused and banished them both. And then, it’s really irritating that Prospero never teaches Miranda to do magic — he just puts her to sleep when she starts to bug him. But if I were a sorcerer you can bet your sweet bippy that my daughter would be conjuring up earthquakes and comets by the time she hit 12. Daughters need every particle of whatever weaponry their moms can give them.

They Pull You Back In

The 90-minute conversation between Copeland and Taymor last Saturday was punctuated with clips from her work, including Oedipus Rex, The Lion King, Juan Darién and The Tempest. It became clear after the first clip, from Spider-Man, that the director was in a defensive frame of mind.

Taymor began the few remarks she made about Spider-Man by expressing her aversion to test audiences and the like. “I don’t believe in focus groups at all,” she said. “There’s always something people don’t like. It’s very scary if people are going more towards that […] The audience can’t tell you how to make a show.” She’s none too keen on the Internet, either, as people on the Internet can influence public opinion all over the place from wherever they are. “Twitter and Facebook and blogging just trump you… it’s incredibly difficult to be under a shot glass and a microscope like that […] Shakespeare would have been appalled.” (Although for all Taymor or anybody else knows Shakespeare would be calling all his fans out onto Twitter himself.)

What she really, really didn’t want to talk about was her recent difficulties.

“I’m jumping off of Spider-Man,” she said flatly, to wild applause.

After the clip from Juan Darién, Copeland ventured gingerly to note that one influential critic had not cared for that show: “… if I can name names?? — I think his initials are Ben Brantley,” he quipped nervously, and went on to observe that while he is not “a hater” of the Times’s theater critic, he’d found the review lacking: “I thought well, if you didn’t like Juan Darién… whoever doesn’t like this simply doesn’t understand a certain kind of theater. Nor did he care for the Unnamed Musical …”

“MOVING ON,” declared a visibly exasperated Taymor, to huge applause.

I already knew that Brantley hadn’t cared for the new version of Spider-Man any more than he had for the old one, but what had he said about Juan Darién? Among other things, this: “Ms. Taymor’s skills as a storyteller don’t match her abilities as a weaver of phantasmagorias, and the work has its longueurs. But she knows how to catch her audience off guard with inspired shifts of scale and perspective, and there are times when you may feel exhilaratingly like Alice falling down Wonderland’s rabbit hole.”

This struck me as such an astute and exact criticism of Taymor’s work that I wished I could phone Brantley and ask him all sorts of stuff, such as for investment advice, and what he thinks about Huntsman’s chances.

What We Can’t Rise Above

As the Spider-Man debacle unfolded, I found it easy to believe the reports of story problems, because Taymor, while a superb visualist, really is an indifferent writer with a tendency to become mired in the folkloric and mythological. Her public remarks, though, suggest a deeper reason why the story was hard for her to find.

“Peter Parker is the one who shows us how to soar above our petty selves,” Taymor has said. That is a catastrophically bad reading of Spider-Man, at least in this longtime fan’s view. Peter Parker’s flawed, earthbound part is the crux of the story. His owning of his defects, and yet his refusal to give up on the better part of himself, create a sort of third, transcendent Parker: not the scared, nerdy kid who feels unending grief and shame over his responsibility for his beloved uncle’s death, nor yet the superhero who has left a painful past behind, but an adult who can encompass and own the whole truth about himself. This wisdom protects him from superhero hubris, and is rooted in the certain knowledge and acceptance of his own failings. The twin burdens of greatness and smallness are always with Parker, and with Spider-Man. In fact, the key message of Spider-Man is to remember and respect our limitations rather than to try to “soar above” them.

But this isn’t a message that people who believe themselves to be artists who are superior to the common run of mankind are able, maybe, to access very easily. The tacit acceptance of universally human failings seems essential, too, to the use and understanding of irony. And maybe it takes an ironist to do a comic-book story properly.

Comic books are the time-honored property of teenagers, who are generally neck-deep in the worst morass of self-consciousness that most will experience in their whole lives. Classic comic books like Spider-Man are stories purpose-built for just this kind of self-doubt and insecurity, providing a world of in-jokes about the inner workings of the outcasts and nerds who are meanwhile and unbeknownst to all possessed of embarrassing but heroic and exhilarating superpowers. These stories are therefore full of knowing, winking asides about such subjects as acceptance or “coolness,” social power, sex appeal and “being misunderstood.” On the one hand, if you’re a superhero, these subjects are ridiculous; you have a city to save. On the other, who could care about saving a city if you’re in love? In this way, comic books are fables of gentle, absurdist self-mockery.

We are all of us here to be humbled. The message of the original Spider-Man story is that if we don’t acquire humility, patience and self-knowledge through our own will, events will keep overtaking us to make sure we learn and relearn these things the hard way. There’s a Spanish phrase for that, one I learned many years ago in a Venezuelan coconut grove during a hurricane (kidding! but it is a good phrase): “aprender a palos,” “to learn by blows.” Will Julie Taymor rise to the wisdom of Peter Parker?

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like A Gentleman, Think Like A Woman.

Photo of Taymor by ellasportfolio.