The Strange, Great History Of Norman Mailer's $2.5 Million Penthouse

by Evan Hughes

The bad boys who gave much of 20th century American literature its “muscular, glamorous aura,” as one of their daughters, Alexandra Styron, puts it, are beginning to fade from view. So it’s worth sitting up to take note of the fact that the Brooklyn lair of the one you might call the lion king, Norman Mailer, is up for sale. Following the death of his widow, Norris Church Mailer, the nine Mailer children are listing the top-floor apartment at 142 Columbia Heights for $2.5 million. The broker, Dolores Grant of Corcoran, tells the Times that the place does not lend itself to easy comparisons, and perhaps she speaks more truth than she knows.

The killer slideshow accompanying a Times article from last week shows the apartment to be a splendid find for the literary house-hunter, at least in its furnished and book-lined state. But it also appears to be smaller than it has looked in my mind’s eye since I began researching the great enfant terrible for a book on literary Brooklyn.

Domestic drama and unlikely occurrences tended to follow Mailer around, so a lot of wonderfully odd events transpired in that space, including, I’m sure, some that we’ll never hear about. Mailer bought the building with his mother in 1960 and moved in two years later. The delay no doubt had something to do with the fact that in the interim Mailer stabbed his then wife, Adele, at their own Manhattan party, which made things a bit rocky for the both of them. (In her terrific biography Mailer, Mary Dearborn provides a gripping account of the incident, opening with a line from Beat poet Michael McClure: “1959–60 was a great year to fall apart.”)

In 1962, Mailer (who grew up in the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Flatbush and Crown Heights) moved to the elegant house in the Heights with wife number three, Lady Jeanne Campbell. They soon undertook the substantial and inventive renovation that made the apartment the light-filled curiosity you see in the slideshow. Mailer wanted his writing space to be way up near the ceiling and had a carpenter friend build a loft up there. To reach this perch, you had to get to a crow’s nest that led to a catwalk and then to a rope ladder — very pirate-on-the-high-seas. At parties, Mailer liked to challenge his guests to make the ascent. (I like to picture him giving them a big knife that must be held between the teeth, but I’m making that part up.)

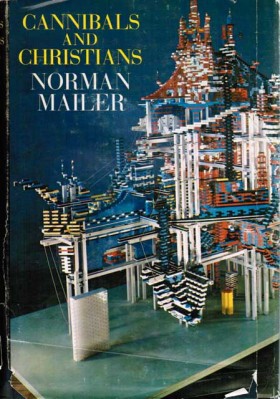

The renovation and rope-ladder contraption were in keeping with Mailer’s interest in building and tinkering; he left Harvard with a degree in engineering. A few years after moving in, Mailer began spending an inordinate amount of time building, in the middle of the living room, a huge imaginary model city made out of Legos. He announced the project in major magazines, underlining his complete seriousness in taking on the ills of modern urban life through imaginative, vertically oriented architecture. At some point the Museum of Modern Art wanted to display the model city, but it was discovered, after talk of a crane-lift, that the thing could not be removed without disassembly, and for Mailer this was a nonstarter. The model, which Dearborn says took up a third of the available floor space in the room, stood there for around five decades.

In 1965 the author threw a party in honor of the new light heavyweight champion of the world, José Torres. Mailer had bet heavily on Torres in the title bout, held in New York, and had planned the fight-night party in advance, and sure enough Torres came through with the victory over Willie Pastrano. (After the 8th round, the referee checked Pastrano’s condition by asking him who and where he was. He replied, “I’m Willie Pastrano and I’m at Madison Square Garden getting the shit kicked out of me.”) Torres joined the boisterous soirée at Mailer’s place, got unusually drunk, went home and passed out (long day), and returned in the morning to find the party still in full swing.

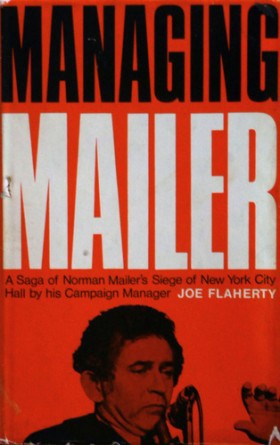

Mailer also convened a merry meeting at the apartment in 1969 to discuss the idea of a run for mayor. To get both attention and advice, he invited some media types, including Pete Hamill, Peter Maas, and Gloria Steinem, who was apparently undeterred by Mailer’s reputation for misogyny. Joe Flaherty of the Village Voice was also in attendance and later wrote, in a curious sentence, “The warmth of the room appealed to my Irish heart; it seemed like a blend of wood and whiskey, combining the best aspects of the womb and the coffin.” Two hours of drinking preceded the actual meeting. Mailer stood at the head of the room, waving around a tall bourbon “like an ever present hand puppet,” in Flaherty’s words. Jimmy Breslin was there, doling out straight talk, and the group agreed that he should join the Mailer ticket, which he did. (Flaherty became the campaign manager and then wrote the book Managing Mailer, which Mailer blurbed by paying the compliment that he wished it didn’t exist.)

After the meeting, Flaherty and a small group parted ways with Breslin outside and then heard his raucous laughter down the block. Breslin stood on the sidewalk, cupped his hands around his mouth, and bellowed at everyone and no one, “Do you know something? That fuckin’ bum is serious!” And in fact Mailer became a tireless candidate, if an atypical one. During the campaign, Mailer was interrupted in the middle of a soliloquy about the departed Brooklyn Dodgers by a young man who brought up the snowstorm that had seriously damaged Mayor John Lindsay’s reputation when the streets were not cleared for days: “What would you have done about the snow in Queens?” The correct answer to this question was obvious, but Mailer gave a different one. “I’d piss on it,” he roared.

In 1976, the apartment on Columbia Heights, now shared by Norris Church, served as the venue for an anniversary party for Doris Kearns and Dick Goodwin. Attendees included Jackie Onassis, Bob Dylan, Woody Allen, Joni Mitchell, Kurt Vonnegut, Ali MacGraw, a senator or two, and Hunter S. Thompson, who overstayed his welcome. (The list goes on from there, and as I look at the Times slideshow I keep wondering how everyone fit, what with all the Legos.) Christian Lorentzen in the New York Observer:

Hunter Thompson, among the last to leave, came back and rang the doorbell at 6 a.m., asking for bacon and eggs, which [Norris Church] duly served up. Mr. Thompson crashed in a hammock in the Mailer living room, flipping out of it at 3 p.m. Sunday afternoon. “Thanks for a great party, Norris,” he said on his way out.

Mailer was not yet married to Norris at this point; in fact, he was married to Beverly Bentley Mailer, who had exchanged vows with him in this very apartment in 1963. In the fall of 1980, he finally got an acrimonious and costly divorce from Beverly. The financial fallout meant that he had to sell off the lower floors of the Heights building so he could buy back his house in Provincetown, MA, which had been auctioned off. (Long story.) Mailer now wanted to marry Norris. Problem was, he had had a child with another mistress, Carol Stevens, and he wanted to man up, as it were, and give the daughter “legitimacy.” For him, the solution was clear: he married Carol on a Friday at 5 p.m., flew to Haiti two hours later to secure the divorce, returned the next day, and married Norris three days later in, where else, the living room on Columbia Heights. Liz Smith scored the scoop on this story, which got widespread attention and produced the headline “TRIGAMIST!” Norman and Norris left the reception while it was still crowded with A-listers so they could fly to London, where Mailer had a bit part in Milos Forman’s film Ragtime.

One of Mailer’s Brooklyn guests the following year had a particularly eyebrow-raising past. Jack Henry Abbott began corresponding with Mailer from prison in 1978. He was serving 20 years for murder and had heard of Mailer’s interest in the Gary Gilmore case, which the author eventually documented in The Executioner’s Song. Mailer helped Abbott, a self-made intellectual, to publish some of his letters in The New York Review of Books and then land a book deal. He came up for parole in 1981. In a plausible reading of his correspondence, he himself had warned that releasing him was a poor idea. But he was approved for parole, presumably in part because Mailer had extended him a job offer as an assistant upon release.

Mailer met Abbott’s plane at JFK late at night on the day he was released, and the two went back to Mailer’s place to have a celebratory drink on the terrace. A month later, Abbott killed a young waiter in the East Village with a knife through the heart. In an incredible irony and journalistic embarrassment, this stabbing, based on a petty misunderstanding, occurred the day before Abbott’s book received a prominent favorable review in The New York Times Book Review, which had already been printed. When the paper landed on stoops, the author was a repeat murderer on the lam, and he was not caught until months later, in New Orleans. Mailer did not handle the media firestorm well, conceding only when backed into a corner by criticism, “I have blood on my hands.”

It was around this time that Mailer came under federal investigation in connection with a large-scale smuggling ring that ran hashish into the country by sea. Mailer knew several of the key players, and a number of them were eventually arrested. It appears that during the years-long investigation, the authorities were targeting Mailer, a big-name fish. “The feds were into star-fucking,” the fallen kingpin, Richard Stratton, told Dearborn decades later. (Good get, Ms. Dearborn.) At some point Mailer’s place was broken into and ransacked, and it looked like the work of law enforcement. Nothing was reported stolen, but a bag of Mailer’s pot was placed in the center of his bed.

Stratton also told Dearborn that he had once stood with Mailer on the Brooklyn Heights promenade just outside Mailer’s apartment and described to the writer how a huge shipment had come into the Brooklyn docks just below them. But no one has been able to determine Mailer’s role in the drug ring, if he had any. His friend Buzz Farbar (who had been at that mayoral planning session years before) got arrested and agreed to wear a wire over lunch with Mailer at Armando’s, a restaurant still in operation on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights. Mailer said nothing to incriminate himself and he never faced any consequences. Instead he went on writing and living part-time at the Columbia Heights penthouse until his death, at 84, in 2007. Someone suitably outrageous ought to buy the place.

Evan Hughes’s book, Literary Brooklyn, a work of literary biography and urban history, will be published in August by Henry Holt. He’s on twitter.

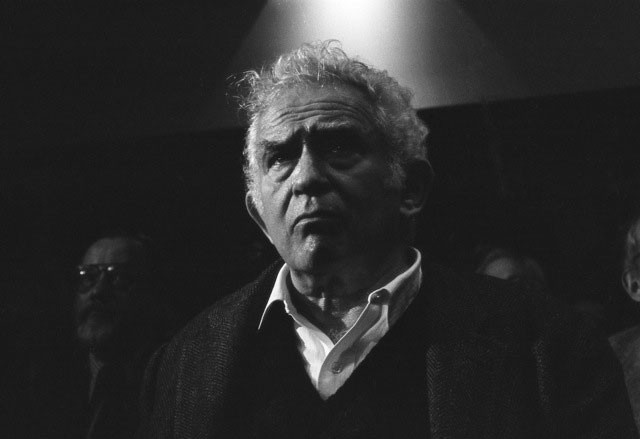

Photo by Dominique Nabokov. Used with permission.