May 21: The Rapture Meets My 40th Birthday

by Maud Newton

As lead-ups to fortieth birthdays go, I recommend steering clear of subway preachers who forecast the Rapture for the very day you’re most dreading. For 18 months now, End-Timers have been gathering daily, at the top of the stairway to the train I take home from work, to press “Judgment Day” tracts on unsuspecting commuters. I’m sure someone else, someone who lacked my fundamentalist baggage, would’ve laughed at the coincidence and shaken it off, but to me it felt personal when the men turned up there, with their pamphlets and placards and dire predictions, as though the God I grew up fearing and eventually turned my back on had orchestrated some final absurd cosmic joke. Of all the dates in all the centuries over more than two millennia, why May 21, 2011?

My mother, a former preacher, would call it a warning. She may not have her own church anymore, but she still believes the Second Coming is nigh. She may, in fact, actually expect to be whisked off to heaven on my birthday. I’m not going to ask. After a six-year break from each other (it’s complicated), we get along really well now that we don’t argue about God anymore; when she alludes to Him or anything else I don’t want to talk about, I change the subject. I’m an increasingly fervent agnostic, if there can be such a thing: compulsively uncertain, committed to doubt. I don’t believe in any deity — and certainly not the Christian one, whose unfairness and sadism are so repellent that even if He did exist I would gladly forgo His company to burn in hell with people I actually like.

The tedium of heaven is obvious, I know, and, having been so roundly mocked by so many, barely merits further remarking upon, but my grandmother, my mom’s mom, once had a near-death experience, dreamed of a lavish mansion reserved for her in heaven and awoke cursing at the prospect of spending eternity there. Is it possible to imagine a more dismal place than one where there is no sex and no joking and everyone sings all the time?

A confession, one sure to enrage fervid atheists: though I don’t expect the End of the World to be set in motion this Saturday night, I wouldn’t be entirely surprised if it were. Fatalism comes easy when you grew up bracing for the apocalypse, being told that that, sometime very soon, probably next year but possibly tomorrow morning, a fiery mountain would fall into the sea, the oceans would turn to blood and then the moon would, and soon after that a third of all living things on the earth would die. Never mind homework, forget the boy you had a crush on, it would be best to turn down the lead role in the school musical, for there was no time to waste. Jesus could return at any moment, that was the crucial thing, and it was our duty to spread the word. Also, to repent, because if you hadn’t been forgiven for every sin you’d ever committed, no matter how tiny, even if you didn’t know it was a sin, you’d be regrettably yet decisively Left Behind. Rapture Readiness is a hilarious cliche in the popular culture now, but it’s no joke when you live it. I can’t tell you how many nights I lay awake, obsessively begging the Lord for forgiveness, at the age of eight.

You get steeped in this stuff as a kid, even if some part of you was always skeptical, it’s hard to lose the residual sense that everything unfolding in the world — from natural disasters to commerce and geopolitics — signals some approaching doomsday. Or maybe this sort of existential dread is actually just genetic. It seems to run in my mom’s family.

***

Perhaps you’re gearing up to spend May 21 at a Rapture party or gassing up your car for some post-Rapture looting. Some of you may even expect to end the night seated at the right hand of God. I intend to be touring the bars of Provincetown — “an absolute sink of corruption,” my friend Joan assures me — drunk as a clam at high tide, when the hour arrives.

Obviously, given that it coincides with my fortieth, I’ll have much more on my mind than Jesus’ failure to return. The withering of my body, the decline of my intellect (such as it is), and the rapid approach of the grave, not to mention my continued failure to finish, to my satisfaction, the last two chapters of this godforsaken book I’m writing. Just to offer some highlights.

Compared to the hardcore Rapturites, though, I’m in pretty good shape. Did you hear the interviews on NPR last weekend? “It broke my heart,” my friend D.E. said in email. “There was this one couple with a baby and one on the way and they’d pretty much spent their last dime. You have to just hear the voices of these people. They’re totally lost.” She’s right, it’s tragic.

The architect of this particular Rapture scare is Harold Camping, a former engineer who claims to have found numerical clues in the Bible. He “first predicted the end would come Sept. 6, 1994” but now contends that, as of that date, he simply “had not completed his biblical research. ‘For example, I at that time had not gone through the Book of Jeremiah,’ he explains, ‘which is a big book in the Bible that has a whole lot to say about the end of the world.’” On his blog, Camping writes: “Many of you have contacted me to ask what I will do on May 22, after the May 21 Judgement [sic] Day. I’ve been asked what I will do with my things, and if I will give them away to those who write an entire one line email to me. After the May 21 Rapture, many of us will no longer be here, but this blog will live on. I have scheduled new posts to come out between May 21st and October 21st 2011, that will help those dealing with the End Times of the Apocalypse. [Emphasis mine.] If you do not think you will be saved in the May 21 Judgement [sic] Day Rapture, then please bookmark this page now to visit on May 22.” “Now that’s service,” D.E. said.

“If I’m here on May 22, and I wake up,” Camping told NPR, “I’m going to be in hell.” My favorite rejoinder to his predictions? “After He stood me up on September 6, 1994? He could’ve at least called!”

***

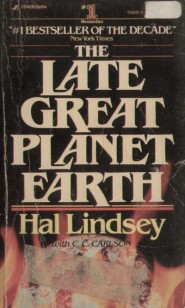

An unusual aspect of Camping’s Judgment Day catechism is that, like the Puritans’ and the Presbyterians’, but unlike most evangelicals’, it rests on the notion of predestination — that some people, the elect, are chosen by God for salvation, while the rest will perish. I say “unusual” because Rapture-readiness scaremongering originated with Hal Lindsey’s bestselling 1970 book The Late Great Planet Earth, which is decidedly not a predestination text. Lindsey, like the Methodists and the Baptists and the Pentecostals, is a big-tent guy. If you ask Jesus to forgive your sins and invite Him into your heart, under the Lindsey doctrine you are guaranteed salvation. This openness, with its emphasis on God’s endless capacity to forgive, has been the emerging trend in Protestantism, so it’s a little surprising to see Camping’s date — and far more restrictive vision of Eternal Life — getting so much attention.

For his part, on his own website, Lindsey — who once wrote, “the decade of the 1980s could very well be the last decade of history as we know it” — offers the following wisdom: “I want all of my friends to know that I AM AGAINST any form of predicting a specific day that the end of this age and the Rapture will occur. I am well aware that a Christian teacher has predicted that the end of this age will occur on May 21st 2011. When this fails, it will be used by our enemies to discredit the expectation that the Rapture could take place at any-moment.”

All of which is to say that the End Times fables of fundamentalist Protestants are multitudinous and fractious; minor denominations have actually splintered over them. A popular wall poster in the 1980s — one forever selling out of stock and being reordered at my mother’s storefront church/bookstore — depicted cars and planes crashing as their righteous drivers rose, ethereal and glowing, into the sky. Jesus would whisk the believers up to Heaven, my mother explained, and the heathens remaining would have to endure not just the aftermath of a million fiery collisions but the rest of the Tribulation. You could still be saved if you weren’t Raptured up, but it would be difficult. I’d go over the details, but it seems wrong to lead you any further into this doctrinal thicket.

Suffice it to say that there are a thousand iterations, at least, of the Rapture story, each with its own creative, deeply punitive twist. If you’re looking for confirmation in the plain language of the scriptures, however, you won’t find much. John Nelson Darby invented the pre-tribulation Rapture doctrine in the 19th century by stitching together verses from various parts of the Bible.

Mark Twain once wrote about the trouble he had gathering material for his childhood biography of Satan. “There were only five or six [facts],” he recalled. “You could set them all down on a visiting-card.” With the help of his Sunday school teacher, “on fifteen hundred other pieces of paper we set down the ‘conjectures,’ and ‘suppositions,’ and ‘maybes,’ and ‘perhapses,’ and ‘doubtlesses,’ and ‘rumors,’ and ‘guesses,’ and ‘probabilities,’ and ‘likelihoods,’ and ‘we are permitted to thinks,’ and ‘we are warranted in believings,’ and ‘might have beens,’ and ‘could have beens,’ and ‘must have beens,’ and ‘unquestionablys,’ and ‘without a shadow of doubts.’” Predictions of the impending apocalypse have about the same level of textual support. “What God lacks is convictions — stability of character,” Twain quipped. “He ought to be a Presbyterian or a Catholic or something — not try to be everything.”

***

My mother was raised an atheist by an atheist Texan mother who herself had a stridently atheist Texan father. As far as I know, Mom remained contentedly godless through college. When I was three or four, she and my dad became Presbyterians, but she soon started reading the Bible for herself and questioning the catechism and she ultimately left the flock in fury over predestination after the minister told the parents of a boy killed by a speeding car that his death had been God’s will. My parents’ attempts to compromise on other denominations didn’t go so well; Mom argued with the pastors and the Sunday school teachers; the Baptists actually asked us to leave. Soon she had her own Bible study, and was speaking in tongues and laying hands on the sick and casting out demons, and eventually, first in our living room and finally in a warehouse, she had her own church. People were scandalized; a woman preaching was an aggressive act.

What’s most remarkable to me now about her sudden religiosity is that the zeal and the leadership impulses that seemed in my childhood to spring up out of nowhere have forerunners she was barely, if at all, aware of. One of her grandmothers was a “devoted Pentecostal ‘holy roller’” (my mother’s words) who not only donated her son’s insurance proceeds (from an accident that left him a paraplegic) to the church but, at some point at least, actually lived in it. Mom knew this growing up, but vaguely; her dad’s family was something of an abstraction. Then, a few years ago, long after her own place of worship was shuttered, she learned that her maternal grandmother’s sister and niece had joined together and “voluntarily started and pastored the only church in Stockard for many years until they finally got a man to come in from somewhere and take over.”

Okay, it’s not as if religious fervor was scarce in 20th-Century Texas. But recently I discovered that Mary Bliss Parsons, my ninth great-grandmother and my mom’s eighth, beat witchcraft charges — twice — in Northampton, Massachusetts, where her husband Joseph moved the family because Mary couldn’t get along with the people of Springfield. She was beautiful and opinionated, with a “harsh,” “often accusatory” manner, and she was given to “fits” that incited Joseph to lock her in the basement. According to the authors of Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England:

She and her husband were frequently and notoriously at odds with one another. During part of their time at Springfield he had sought to confine her to their house. (Otherwise, he said, “she would go out in the night … and when she went out a woman went with her and came in with her.”) When this tactic failed, he locked her in the basement. It was then, she claimed later on, that she had first encountered her “spirits.” There was at least one quite public episode — again at Springfield — that amounted to a family free-for-all. Joseph was “beating one of his little children, for losing its shoe,” when Mary came running “to save it, because she had beaten it before as she said.” Whereupon Joseph thrust her away, and the two of them continued to struggle until he “had in a sort beaten [her].”

Witchcraft accusations surfaced soon after the family settled in Northampton. Mary gave birth to a healthy baby boy — her fifth child — and the following year a neighbor’s newborn died. When the grieving mother claimed Mary had cursed the baby, Joseph tried to protect the family’s good(?) name by going on the offensive. No stranger to the courtroom, he initiated a defamation suit against the neighbor who’d started the rumors. This approach was tricky, and fraught; while the “immediate outcome of [slander] actions was usually favorable to the plaintiff,” the “long-range effects were mixed.”

Sure enough, Joseph prevailed, but suspicion and ill-feeling roiled until new witchcraft claims landed Mary in court again 18 years later. This time she was the defendant. Most of the evidence from the criminal trial has been lost, but the indictment remains:

Mary Parsons, the wife of Joseph Parsons, … being instigated by the Devil, hath … entered into familiarity with the Devil, and committed several acts of witchcraft on the person or persons of one or more.

Ultimately the jury acquitted her, but Mary’s case is seen as a precursor to the Salem Witch Hysteria of 1692.

It’s interesting, to me at least, to ponder the parallels between her story and my mother’s life. Both women were difficult and nonconforming and, by some accounts, mad; both purported to encounter spirits; both were accused of Devil Worship. When I was a child, the Presbyterians and Baptists all but called Mom a Satanist as they showed us the door. The legacy of loudmouthed, intractable women might run back in the other direction, too. By all accounts Mary’s mother Margaret was prickly and litigious, a force among Puritans.

I can’t speak for the rest of the gene pool, but the women in my branch of Mary’s tree are basically all, in different ways, misfits. Eccentricities and diagnosable mental illnesses vary, but the common theme is an unwillingness to bend to the expectations of polite society, a.k.a. a need to pursue our weird interests and passions whenever, wherever, and however we want.

***

When my incomparable stepdaughter, now 17, was visiting recently, I told her how pathetic I always found it at her age when adults would say, “Can you believe I’m 40? I don’t feel 40! I still feel 22!” And I would look at their eye wrinkles and their dull hair and mom jeans and I would think, Well, you sure do look 40, so suck it up. Jeez. Knowing how obnoxious I was to my mother in my teenage years, I wouldn’t be surprised if I actually said those words to her. I said far worse, that I do know.

Obviously I don’t think 40 is the end of the road — some of my favorite people are closer to twice that. It’s just that some of us age more naturally, more gracefully, more normally than others. I think a lot these days about the fact that I haven’t had children; it’s not that I regret the decision, just that it sets me apart, defines me in some way I’m not sure I was prepared to commit to. I’m a reluctant New Yorker, a loving but irregular wife, a refugee from the practice of law, a blogger who’s lost interest in regular blogging, a critic who never planned to be one and a supposed writer who’s only now finishing her first novel. What the hell, in other words, am I doing with my life?

Before my mom turned 70 last June, we had gone six years without speaking. When I called to wish her a happy birthday, though, we started talking and didn’t want to stop. Her passions are as extreme and unpredictable as always, and sometimes have unfortunate consequences — she sleeps with a shower curtain between her sheets and bedspread so that she doesn’t have to get up in the night if one of her ten dogs has an accident — but they are never boring.

Mom has been a cat hoarder, a bird breeder, a dog rescuer and, of course, a preacher. Nowadays she has turned her attention to fruit trees. My stepfather jokes that she confuses them with sofas because she’s always wanting him to uproot them and move them around. She has 20 apple trees, four apricot, five nectarine, six peach, three cherry, one mulberry, five pear (of four varieties), one plum, a dwarf lemon or two, and four or five elderberry bushes. No doubt this is a sad statement on what one finds interesting at midlife, but I love to hear her talk about them. In fact, at first, my joy at being back in touch with her was so extreme that I would often sit at my computer for the duration of our conversations, quietly typing up everything she said.

“I hit the jackpot last year, as I usually do,” Mom told me last summer. “I went to Kmart in, oh, I guess May or June, and I spied these wonderful dwarf trees that grow to be about six or seven feet tall. They were $50 apiece. I wasn’t about to pay that, but I kept looking at them and looking at them, and they didn’t sell any, so they marked them down to $25, and I bought three, and then they went to $18 and I bought three more, and then they eventually dropped down to $8 and I bought the rest. They don’t give you as much fruit as a great big tree would, but you can’t get the fruit up at the top of a great big tree.” Later, the unseasonable heat had her worried. “I have a whole bunch of grapes. I’ve got thousands of grapes out there, but the leaves that shelter the grapes from the sun are starting to look kind of brown and downcast.” Downcast leaves! This is the way she speaks, bluntly, rhythmically, sometimes poetically. I needed the time away from her, but I also really missed her.

So, does my mother expect to be Raptured up on my fortieth birthday? Does she see me as her wayward lamb, a child out of touch with Jesus who will be Left Behind to endure the Tribulation? Is she, even now, jarring and canning food so that my sister and I will have plenty of pickles, prunes and jams if we can make it down to her house in the midst of the apocalypse? I don’t know.

I do know that she has 40 fruit trees, is obsessed with demons, lives in surroundings more characteristic of Hoarders than Good Housekeeping, is completely self-reliant and seems remarkably happy. Whatever else she is, my mother is living proof that getting older doesn’t predestine anything. And on May 22, 2011, when I awake in Cape Cod with a colossal hangover, all the wrinkles on my face cast into full relief by dehydration, I’m sure that will serve, if not as inspiration exactly, as some sort of consolation.

Maud Newton is a writer and critic best known for her blog, where she has written about books since 2002.

Photo by [mementosis], via Flickr.