100 Years Later, A Black Man Finally Loves Joplin

by Abe Sauer

“I love Joplin! I love Joplin.” So began President Obama in his Sunday address to the town of Joplin, Missouri, smudged from the face of the earth by a tornado a week before.

“I love you, Obama!” yelled a Joplin resident in the audience.

While there is much hope to be had in Joplin’s will to rebuild, there is even more to be found in the obliterated town’s welcoming of Obama. About a century ago, a Joplin lynch mob attempted to drive every last African-American resident out of town, and pretty much succeeded.

It’s been a long time since an African-American publicly loved Joplin, or vice versa.

From the beginning, Joplin had a reputation for wildness even by Missouri frontier standards. Its early years were so crime-ridden, the city had a period that came to be well known as Joplin’s “Reign of Terror.” Lawmen, the nearest of which was usually tens of miles away, rarely dared set foot there. The last time Joplin received this much national attention was when Bonnie and Clyde’s Joplin hideout was discovered and the gang shot its way out of town, killing two officers, including one of the city’s detectives. It was Joplin where the couple’s iconic pictures were found.

And when Joplin last received the attention of an American president, it was just after World War II. Larry Wood, author of Wicked Joplin, wrote that Eisenhower said, in a post-WWII radio address announcing that stationed U.S. servicemen would be allowed to fraternize with local German women, “Now, Berlin will be like Joplin, Missouri on a Saturday night.”

Part of the uglier element of the reputation Eisenhower referenced was forged just after the turn of the century. It’s an event that makes Obama’s visit to Joplin, and Joplin’s response to that visit, so meaningful.

It had been just 50 weeks since a tornado had swept through Joplin, killing four when the town would make the national news, again for disaster. This one was man-made.

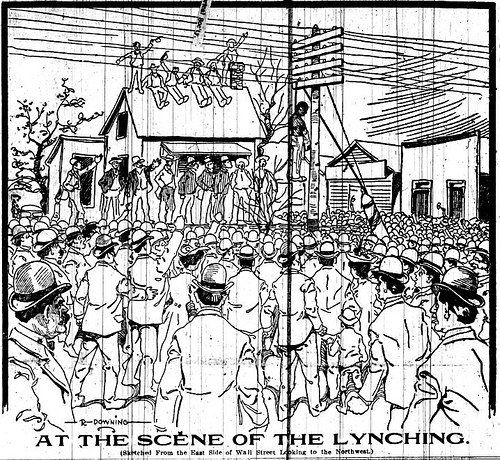

The April 16, 1903 Boston Evening Standard headline read: “Lynching at Joplin, MO. Negroes then driven from the town.” The Standard, like The New York Times report from the same day, referred to the lynched man, Thomas Gilyard, as “a tramp negro.”

The explosion of racial violence in Joplin in April 1903 hardly manifested unexpectedly. After the Civil War, Missouri was notoriously slow to acknowledge the South’s loss, after being fast to support its beginning. From “bleeding Kansas” to Dred Scott, no state lobbied for confrontation more than Missouri. While the marquee battles to the east make the PBS documentaries, a full fifth of all recorded military battles during the war occurred in and around southern Missouri. Those records do not include the pervasive and brutal guerrilla warfare. In the 1864 Centralia Massacre, pro-Confederate insurgent William Anderson had 24 captured Union troops executed. Historians have noted that attacks by Missouri Confederate fundamentalists continued well into the 1880s. Jesse James, present at the Centralia slaughter, would go on to be Missouri’s most famous racist, to be glorified by Brad Pitt, Colin Farrell, porn stars and reality-TV Nazi motorcycle mechanics.

In Joplin specifically, anti-African American violence was bubbling in the months before April, 1903, with Gilyard’s lynching just the apex of several years of racial agitation in the region.

August 1901: In Pierce City, a town 30 miles from Joplin (that itself was destroyed by a tornado in 2003), a mob of a thousand lynched Will Godley.

Earlier that day, the body of a Gisele (some reports “Caralle”) Wild, a white woman, was found in the woods, her throat slit “ear to ear.” The Pierce City mob went to the jail where the suspect was held and, encountering little resistance, dragged Godley outside and hanged him. The evidence against Godley was circumstantial, but deemed “conclusive” by early newspaper reports of the lynching. Unsatisfied, the mob shot at Godley’s body swinging from the Lawrence Hotel — hitting and killing a white boy in the audience.

According to Kimberly Harper’s White Man’s Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsions of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, 1894–1909, in a move that was specific to blooded-up lynch mobs of that period and that region, there was then a call to “run the niggers out of town.” The Pierce City throng descended on the colored section of the town, where it engaged in a firefight with, and killed, African-Americans Pete Hampton and French Godley. Out of ammo, the rioters broke into the Missouri National Guard armory and began shooting at African-Americans, including women and children. Then they torched the houses in that area, residents and all.

Many of the fleeing African-Americans went to nearby Joplin, an influx that probably contributed to a carbon copy of the events 18 months later.

Will Godley was posthumously cleared of guilt, of the murder anyway; he remains guilty of being black in Lawrence County in 1901.

As justifications for lynching went, “negro attacks white woman” was the hit tune of its day. Nothing built an lynch mob faster, or made it angrier and more violent, than the rumor that a white women had been so defiled. It was almost never true; nor was it exclusive to the South.

Though the state rarely makes it into a conversation about 20th century racial violence, Duluth, Minnesota residents lynched three African-American circus workers in 1920, 17 years after the Joplin riots. In typical fashion, authorities surrendered the victims from the safety of jail to a mob that had formed outside after rumors spread that a white women had been raped. Later medical examinations proved no such crime happened. Not uncommon, a postcard of the lynchings was sold.

On May 21st, less than a year after the Pierce City riots, African-American William Jones was arrested in Joplin after the “burly negro” was accused of attempted assault on Mrs. John Parmater. A large crowd of what one report called “infuriated miners” gathered around the jail, waiting for Mrs. Parmater to arrive and positively ID the suspect, after which time it was assumed they would “appeal” to Joplin authorities for his release for rope justice. William Jones was saved, in part, by heavy rains dampening the mob’s spirit.

On May 22nd, Mrs. Parmeter finally showed up to the jail and, according to the Nevada Daily Mail, “after carefully looking at Jones” was “unable to state positively that he was the Negro.”

No such luck for Dudley Morgan, an African American in nearby Texas who, a day after Jones’ narrow escape, was captured and accused of assaulting a white woman. The Arizona Republican described his fate: “The crowd clamored for a slow death and began with burning out the victim’s eyes — many women attended the festivities but on account of the crowd were unable to catch a glimpse of the tortured wretch.”

There had been rumors of lynchings in the rural parts of Jasper County in previous years, but not in Joplin. In 1900, an African American named Barnett had narrowly escaped a Joplin lynching. His crime? Suspicion of raping a white woman.

For Joplin, the third time would be the charm.

On April 15, 1903, an African American named Thomas Gilyard was taken into custody for the murder of a policeman. White Man’s Heaven notes that Gilyward had been arrested for less than an hour before the Joplin streets had filled with around two thousand angry men. The mob soon demanded Gilyard be surrendered to justice.

Reports indicate that town officials made pleas to those gathered about the importance of trials and the law, beyond what authorities often did in the face of such mobs. In many cases, police even did the favor of bringing the men out. In Joplin, the rioters had to break the jail door down itself. The police had been considerate enough to move Gilyward to his own cell, lest the wrong prisoner be served another man’s justice.

The timing for Gilyward could not have been worse.

Not only had Joplin mobs had two recent unsuccessful lynchings, but also the trial of the participants in the Pierce City riots had just concluded in February, with not-guilty findings all around. It was a widely covered trial that many nearby Joplin residents certainly followed. The lack of convictions in the results could only have served to embolden the growing mob. Add to this, the fact that many of the African-Americans fleeing Pierce City came to Joplin.

The New York Times report of the event notes that “the first act of the mob after hanging the negro was to demand the release from jail of a local character known as ‘Hickory Bill’ under arrest on the charge of assaulting a negro.” The Boston Standard report notes that this demand “was granted.”

After driving all the African-Americans from the streets to the north “colored” part of town, the Times says that the houses were “fired” while “the mob made endeavors to prevent the Fire Department from extinguishing the flames and were partially successful.”

“Reuter’s dispatches” reported that “several hundred” Pierce City residents, apparently unfulfilled by their work a year earlier, hurried to Joplin to join in the chaos and murder.

In the riot’s aftermath, authorities, in what would become standard practice in the coming decade, spirited away to the county jail another African-American who had been seen with Gilyard before the shooting.

The Joplin lynching was national news not for the lynching, but for the subsequent riot that aimed to exterminate the town’s African-American population. This is cast in stark contrast by the April 17th report on the incident in Iowa’s Carroll Herald. Printed just below a long telling of Joplin events is a brief note, almost like a correction, titled “Innocent Negro Killed.” It reported that Ed Porter, an African-American who had been burned to death the day before in New Orleans for the murder of a white woman, was innocent “beyond any cause for doubt.” A lynching was only news if accompanied by something more important. Joplin was more important.

Harper wrote:

…Rather than simply showing a black community how it was expected to behave, white mobs entirely destroyed African American communities… one can argue that expulsion was one of the most extreme forms of social control as African Americans were forced to leave behind everything they had worked for and demonstrated their weakness as they could not prevent expulsion, and it sent the message to nearby black communities to remain complacent or else face the same fate.

The same sad tale would play out 75 miles away in 1906.

On April 14th, almost three years to the day after the Joplin lynching and riot, a Springfield mob removed from jail and lynched two African-Americans. They later returned to lynch a third. Then they burned all three for the crime of raping a white woman, for which they were later found innocent. Once again, African-Americans fled.

The lynching and riot in the Queen City of the Ozarks was so gruesome and widely reported that it largely scrubbed from memory the smaller previous incidents in Pierce and Joplin.

In the wake of the Joplin lynching and riots, a tired story ran its course. Politicians proclaimed searches for justice. Names were named. But really only three. “Hickory Bill” was acquitted, as was another man. In June of 1903, one man, Sam Mitchell, was found guilty of leading the mob, and being the one who hung the rope. He was sentenced to ten years in prison.

After his retrial in November, Mitchell was freed — despite his alibi’s subsequent arrest for perjury.

Summing up the sentiment of the community was a widely printed letter from an anonymous Africa- American former slave, a 30-year resident of the town. From the version printed under the headline Titled “What is left in life for a negro in Joplin?” in the April 20th Chicago Daily Tribune:

“I call my home, Joplin. I suppose the money I have paid in the way of taxes has gone to school funds to educate people such as came to my house last Wednesday night and broke out my window panes and routed my wife and children and scared them nearly to death. I found them in a box car near the railroad track… and I sit in my house and hear the howling fiends utter oaths that drove me mad: ‘Get out, niggers, this is a white man’s town.’

Now, would I say again. I would say, O Lord, if there is any, have mercy on my soul, if a black man who lives in Joplin has any.”

The Joplin and nearby Pierce City mobs accomplished their goal, significantly reducing their respective African-American populations. Lawrence County’s African-American population was a third its size ten years after Pierce City.

Ironically, in the years after the lynchings, Joplin residents complained about the press sullying the community’s name by connecting it with the actions in Pierce City.

For years, the legacy of the riots informed race relations in Joplin. In November of 1912, when a “negro minister” was charged with “entertaining young white girls in his office,” authorities, fearing another riot, whisked him and “an accomplice” away to the county jail, despite the minister’s insistence of innocence. Hearing the news, much of the remaining and rebuilding African-American population of Joplin left.

Four years later, in 1916, Jasper County authorities were doing the dance again. Fearing another lynching, police sneaked from one jail to anther an African-American charged with the robbery and shooting of a train conductor just outside Joplin.

Pierce City and Joplin have made pains to forget these incidents. When a local newspaper editor created an exhibit of the Pierce City lynchings in 1991, it was removed after complaints. Meanwhile, the first half of Joplin’s city motto is “Proud of Our Past…” While its local paper, The Joplin Globe, willingly reports on Pierce City’s lynching and its subsequent inclusion in the Independent Lens documentary about African-American ethnic cleansing, Banished, it almost never mentions Joplin’s own similar incident, even if the town’s present clearly still struggles with its past. (To this day, Joplin itself is about 90% white, and Jasper and Newton counties are about 92% white.)

What would Hickory Bill say today as an African American president walked amongst the debris of his ruined city? Would Sam Mitchell again have flung up his rope? Probably neither; had both Joplin men had their way, Obama never would been born, his father hanged from some unknown pole, charged, if not convicted, of polluting a white woman, even if she was a Kansan.

In the bigger picture, 100 years is not a particularly long time; and yet when a white Joplin youth approached Obama on Sunday and excitedly asked for an autograph on his shirt, it might as well have been an eternity. The President grinned and obliged and they slapped one another on the back chummily, both likely numb to the history that was and the history they were.

One hundred years after “a negro of Joplin” publicly questioned if “the people of Joplin are so hardened” that they had forsaken the “love of God,” another publicly told the people of Joplin God had blessed them, fulfilling the second part of Joplin’s motto “…Shaping Our Future.”

One hundred years after the darkest moment in the city’s history, a black man loved Joplin… and Joplin loved him back.

Abe Sauer can be reached at abesauer at gmail dot com. He is reluctantly on Twitter.

Joplin Globe illustration via Historic Joplin.