When Alan Met Ayn: "Atlas Shrugged" And Our Tanked Economy

That pill-popping, boy-crazy nincompoop Ayn Rand has got a lot to answer for. Indeed, it’s not too much of a stretch to say that we owe at least part of the recent economic crisis to her and her philosophy of Objectivism, since former Fed chief Alan Greenspan was a lifelong disciple of both.

The two first met in the ’50s. Back then, a gang of acolytes, calling themselves the Collective, used to gather at Rand’s apartment on East 36th Street every Saturday night so they could tell each other how smart they all were. Along came Greenspan one evening, shy and somber.

It took a while for Greenspan and Rand to warm to one another. She nicknamed him “the undertaker,” owing to his dark clothes and mournful air, and he, a self-avowed logical positivist, required a certain amount of wooing on the philosophical side. But in time he became fiercely devoted to Rand, one of her most trusted confidants; he taught her something of the economics she shoehorned into Atlas Shrugged. He wrote for The Objectivist magazine, and stayed a close friend until her death in 1982.

Though the schemes of both these idealists crashed mightily and catastrophically to earth, both steadfastly refused ever to regret or repudiate the follies of Objectivism. The shocking thing is that despite all the evidence — which could not possibly be more damning — many on Wall Street and on the right continue to insist that Ayn Rand is a genius and that Objectivism is the answer to all mankind’s problems.

If that were so, doesn’t it stand to reason that the top genius’s own life would demonstrate at least a few of the benefits of being an Objectivist? Which, sadly, it really, really does not.

Greenspan’s tenure of nearly two decades as the chairman of the Federal Reserve is the second longest in history. Shouldn’t he have bestowed on a grateful public a legacy demonstrating the wisdom of Objectivist laissez-faire policies? We know how that turned out, too.

There’s about to be a movie, ostensibly the first of a trilogy, of Atlas Shrugged, Rand’s magnum opus. The trailer is absurd but mesmerizing, and it quickly gained over a million views on YouTube. Paul Johansson, an actor and neophyte director best known for his work on “One Tree Hill,” seems to have done a fine job with a tiny budget of somewhere between $15 and $25 million; the production looks terrific, sparkling with evening gowns and champagne, like a hopped-up version of Dynasty (which, come to think of it, Atlas Shrugged really does kind of resemble.) “If you double-cross me, I will destroy you,” the sleek blonde in the business suit informs her foe, with less conviction than an ordinary person would employ in ordering a salad. If the trailer is to be believed, this movie has a lot of campy pleasure in it. I kind of can’t wait!

Atlas Shrugged is about the tender love of a beautiful girl for her railroad, and also for a heap of powerful, visionary men. Nietzsche meets Harlequin, basically. It is also intended as a manifesto and rallying-cry for Objectivism: an XXL-sized political pamphlet.

Okay, so what is Objectivism, exactly?

In 1959, Mike Wallace asked Rand to “capsulize” her philosophy, which she proceeded to do, in a Boris Badenov accent and a comically self-satisfied manner.

I am primarily the creator of a new code of morality which has so far been believed impossible, namely a morality not based on faith, not on arbitrary whim, not on emotion, not on arbitrary edict, mystical or social, but on reason; a morality that can be proved by means of logic which can be demonstrated to be true and necessary.

Now may I define what my morality is? [I guess.] Since man’s mind is his basic means of survival […] he has to hold reason as an absolute, by which I mean that he has to hold reason as his only guide to action, and that he must live by the independent judgment of his own mind; that his highest moral purpose is the achievement of his own happiness […] that each man must live as an end in himself, and follow his own rational self-interest.

Mike Wallace could scarcely believe his ears. His pop-eyed astonishment is a big part of what made this interview such great television.

Nietzsche Was Her Homeboy

Rand’s commitment to egoism as the basis for morality began as a reaction against the “collectivist” impulses she reckoned to be responsible for the collapse of Russia, where she was born in 1905. Her family’s wealth had been grabbed in the Revolution, so it’s no surprise that Rand would be anti-Communist. What is a surprise is that she would suppose as she did that the “altruistic” motives of Communism were to blame for everything that went wrong in her native country.

Objectivism is 100% pro-individualism and anti-altruism. Rand believed that altruism is literally wrong, that it weakens the all-important Individual and his chances of finding happiness. She took most of her shtick (enthronement of the Will, super-individualism, exaltation of “artists,” atheism, the Übermensch who is superior to the regular kind, etc. etc.) straight from Nietzsche, although she later denied his influence, claiming only Aristotle (!) as a philosophical forebear. But according to Rand biographer Jennifer Burns (whose book Goddess of the Market: Ayn Randand the American Right is really good), Rand’s early notebooks and journals all but feature little hearts drawn around Nietzsche’s name: “Nietzsche and I think,” “as Nietzsche says,” and so on.

The possibility that the unfettered egoism of guys like Stalin was the main problem with the Russian government, rather than too much altruism, escaped Rand entirely. As someone whose family likewise hails from a Communist country, I find it bizarre that this was not obvious to her. When all the big houses, all the money and privileges in a society accrue to just one class of people, it is safe to conclude that those people are acting out of self-interest and not altruism or whatever other bogus virtues they are ascribing to themselves. Just watch who gets richer, if you want to know what the real motivation is. Not to put too fine a point on it, Stalin was probably about the greatest Objectivist who ever lived, with a few possible exceptions like Mao Tse-Tung, Hitler and Pol Pot.

After the 1929 crash, many in the West believed that some form of Communism was inevitable in the developed world. For a long time American (and Knifecrime Island) intellectuals generally believed that Stalin was a fine man who was just trying to do the best he could for his people; that enraged Rand, who’d arrived in the U.S. in 1926 and knew the score. It wasn’t until the Non-Aggression Pact between Stalin and Hitler became public in 1939 that Americans really turned conclusively and permanently against Communism.

The Fountainhead, Rand’s first real go at a manifesto, was published in 1943. Though reviews were mixed, the book was a runaway success both as a publishing phenomenon and as a calling card for Objectivism. A movie was made in 1949, directed by King Vidor and starring Patricia Neal and Gary Cooper. Rand was at the zenith of her success with the public, celebrated and admired in New York, Ginger Rogers and Ira Levin wrote her fan letters, and the Collective began to collect around her.

Atlas Heaves into View

Into this milieu came Greenspan, age 26, dragged along by his first wife, Joan Mitchell.

Although very young, Greenspan was already a successful economic analyst whose consulting firm, Townsend-Greenspan & Co., Inc., was paid hefty sums to figure out what the hell was being said in government reports and things. Unlike most of the other Collectivists, who were students, Greenspan had something concrete to contribute to Rand’s work. She asked him all sorts of questions about the steel and railroad industries relating to her new novel. He, for his part, thought she was the smartest person ever, saying, “talking to Rand was like starting a game of chess thinking I was good, and suddenly finding myself in checkmate.”

The Collective was convinced that all mankind would rush to become Objectivists the moment Rand’s next novel was published. It was called Atlas Shrugged, and for once the words “eagerly awaited” were for real. A gap of 14 years separated the first blockbuster and the second. But there was an anger, contempt and malevolence toward the common man in the second book that had not been present in the first one. This time the reviews were scathing.

In Atlas Shrugged Rand creates a world where there are people who deserve to live because they are “intelligent” and “creative,” and those who do not. The former set out to rid themselves of the latter. These “men of the mind,” whom their author clearly worships, go “on strike” and refuse to be creative any more, which means that everybody else must perish. And because it’s a work of fantasy entirely under Rand’s control, they all go ahead and obediently perish. (IRL, people were not quite so obedient, as we shall see.)

For those who are inclined to find such ideas ludicrous, the book will fail, and utterly; its premises betray a bottomless ignorance of the deep interconnectedness of humankind, and the needs — economic, social, emotional, intellectual — of one human being for another. In the real world, someone is growing lettuce, someone else is writing a book or feeding a baby, yet another is designing the rails of a high-speed train. Someone else is teaching six-year-olds to read. All of us benefit from all of these activities — sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly. Each life can and does touch many thousands of others. The idea of the Nietszchean Superman who acts against his fellows (whom Rand called “the mob” and “looters” and whatnot) is consequently fatally flawed. Not even the Superest Superman can grow all his own food, make all his own paper, design and build his own cars and airplanes, etc. (Hadn’t Rand ever read Robinson Crusoe?) Humanity is a collaborative project, as well as a project of individuals.

This is to say nothing of the flatness of the book’s characters, its clanking exposition, its interminable speechifying or the woodenness of its dialogue. On the upside, there is a character named Francisco Domingo Carlos Andres Sebastian d’Anconia. Not even Baroness Orczy had that kind of nerve.

Atlas Shrugged burst onto the scene in 1957 and was promptly and categorically reviled from both right and left, as it has continued to be. It also sold like hotcakes, as it still does.

Whittaker Chambers’s famous takedown of Atlas Shrugged, “Big Sister is Watching You” appeared in The National Review in December of 1957. Rand claimed never to have read it (mmmhmm) but refused to let anyone so much as mention Chambers in her presence.

He wrote, “Out of a lifetime of reading I can recall no other book in which a tone of overriding arrogance was so implacably sustained. Its shrillness is without reprieve. Its dogmatism is without appeal. In addition, the mind which finds this tone natural to it shares other characteristics of its type. 1) It consistently mistakes raw force for strength, and the rawer the force, the more reverent the posture of the mind before it. 2) It supposes itself to be the bringer of a final revelation.”

This essay and its message stood between many on the far right and a potentially fervent embrace of Objectivism. After all, Chambers was the pumpkin-growing former Communist who became a bona fide ferreter-out of real live Communists In Our Midst, having been responsible for sending Alger Hiss to jail; and if there is anything a hard-right conservative used to love more than putting Communists in jail, it was a former lefty who’d come over to the other side, like Ronald Reagan. That is, after all, what they hope is going to happen to all the lefties.

Other reviews were not so much negative as incendiary. In Esquire, Gore Vidal wrote that Objectivism was “nearly perfect in its immorality.” Time’s reviewer asked, “Is it a novel? Is it a nightmare?”

So the loyal Alan Greenspan, then around thirty years old and already a big shot in financial circles, wrote to the New York Times to defend the book as follows: “’Atlas Shrugged’ is a celebration of life and happiness. Justice is unrelenting. Creative individuals and undeviating purpose and rationality achieve joy and fulfillment. Parasites who persistently avoid either purpose or reason perish as they should.”

Note how human fulfillment is distributed here in Randian terms, to the “deserving”, whereas the “parasites” are going to go up in flames “as they should.” It is a little chilling to hear a grown man say that sort of stuff, particularly a grown man who will come to have that much influence over the fortunes of so many.

Greed Is So, So Good

So why have so many loved (and still love) this book so very much?

In addition to praising people for being selfish and money-worshiping, Atlas Shrugged has a second rare virtue — a real one, this time — a genuine fascination with business. Few novels of the twentieth century provide a halfway credible or interesting take on business, largely because the arcane details that go into running one are hard to dramatize well. (There are exceptions, of course. James Clavell is great at this, and so is Eric Ambler. Best of all, maybe, is Nevil Shute, whose A Town Like Alice is the novel Ayn Rand or anyone else should have wished she could write. It has got business, suspense, romance, exoticism and adventure, and is a pure delight to read.)

Even today, financial and business types are drawn to Atlas Shrugged for its unusual preoccupation with industry and economics. Plus, it’s not just that literature does not ordinarily occupy itself much with business; literary sophistication is not a prized quality on Wall Street or in business circles generally. Across the table from you, a VC or Wall Street guy will wax all lyrical about Atlas Shrugged and you’ll say wow, you read novels? If you ask what other books they like, though, they might mention The Art of War, which has been a big deal with them since the ’80s, or maybeThe Big Short, or a biography of Warren Buffett. (But not Griftopia! Heh.)

Then there’s the matter of egoism, which is where the Libertarian or far-right angle comes in. Rand is all about the Self-Sufficiency. This is why there are no children in her books. In a Rand novel, no one ever helps anyone or even concerns himself much with anyone else. Pitilessness is the highest virtue there is, it signifies Will and Strength and stuff. The weak are “lice” and “parasites”. Atlas Shrugged is almost a caricature of social Darwinism. Gore Vidal explained it this way: “She has a great attraction for simple people who are puzzled by organized society, who object to paying taxes, who dislike the welfare state, who feel guilt at the thought of the suffering of others but who would like to harden their hearts.”

But the self-interest thing really has a nice ring to it, recalling as it does the elegance of Satanism’s single commandment: “Do as thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.” Rand’s books have sold nonstop from the moment they were published because people love hearing how not only can they get away with being totally selfish, it’s absolutely the right way to be. The best way to be, as in, morally the best. EST and the Prosperity Gospel have much the same appeal. And sure, that all sounds fine when you are home reading a book, by yourself, but just go out there and try it. As Rand herself did.

Love Is An Objectivism Battlefield

1968 was the year of doom for the Objectivist cult’s first wave. Rand had been having an on-again, off-again affair for over a decade with her prime minister and heir, the handsome wacko Nathaniel Branden (born Nathan Blumenthal), 25 years her junior.

Both of them were married when the affair began — he, 24; she, 49 — but they rounded up the spouses and talked all four together about how Branden and Rand were going to be lovers, because, yeah, that always works out so well.

Fourteen years into the affair and Branden, now 38, was done with the whole thing. But every time he tried to break up with Rand, she would fly into torrents of rage and yell at him that he had “no right to sex with some inferior woman!” “The man to whom I dedicated Atlas Shrugged would never want anything less than me!” she shrieked. This went on for ages.

Meanwhile, Rand’s husband, Frank O’Connor, was off drinking himself into a stupor, and Branden’s wife Barbara was slowly losing what was left of her marbles.

Finally, unable to put up with any more scenes, Branden informed Rand by letter that their age difference “now made sex with her impossible” for him. She was devastated. But there was worse to come, because Branden had decided not to mention a secret affair he was having with one of his students, a beautiful young model named Patrecia Gullison. Because even though Branden was an Objectivist expressing his Highest Moral Purpose by Achieving his Own Happiness and all, he was also terrified of what would happen when Rand found out about it.

And for very good reason. When Rand did find out about it, she hit the ceiling and summoned Branden to her apartment and fired him and called the spouses in for another group powwow and screamed and slapped Branden’s face multiple times, in the foyer, because she wouldn’t let him in the living room. This, even though Branden had been Mr. Objectivism for years and years, and the Nathaniel Branden Institute had grown into a huge organization for the spread of Objectivism.

Reason, you would think, demanded restraint, and Rand had for decades styled herself the high priestess of Reason. There were relationships, reputations and institutions to protect on all sides, a thriving business, as well as the propagation of a mankind-saving philosophy to see to.

So what! She was a woman scorned.

Which meant that no sensible, rational considerations prevented Rand from publishing a letter addressed “To Whom It May Concern” in The Objectivist that accused Branden and his wife of deception, and (falsely, it appears) of financial hi-jinks — and of generally being bad Objectivists. “I repudiate both of them, totally and permanently,” she wrote, “as spokesmen for me or Objectivism.” A few prominent Objectivists signed this incoherent breakup letter along with Rand, among them — yes! — Alan Greenspan, the future Fed chairman.

The scandal caused lasting damage to Rand’s reputation, and to her organization. Nathaniel Branden would eventually move to California, found new organizations and therapeutic practices, and marry three times more; the beautiful Patrecia, sadly, drowned in a swimming pool after suffering an epileptic seizure in 1977. (Branden’s memoir My Years with Ayn Rand is hot as a pistol, absolutely riveting and danged scary, btw.)

Greenspan Frees The Market

Although the Collective never really recovered from the events of 1968, Alan Greenspan never broke with Ayn Rand. In his 2008 memoir, The Age of Turbulence, he writes, “[o]f all my teachers, Arthur Burns and Ayn Rand had the greatest impact on my life… Ayn Rand expanded my intellectual horizons, challenging me to look beyond economics to understand the behavior of individuals and societies.” He speaks warmly of her throughout the book, even knowing all that he did about her skeleton-packed closet; his loyalty elicits both sympathy and exasperation.

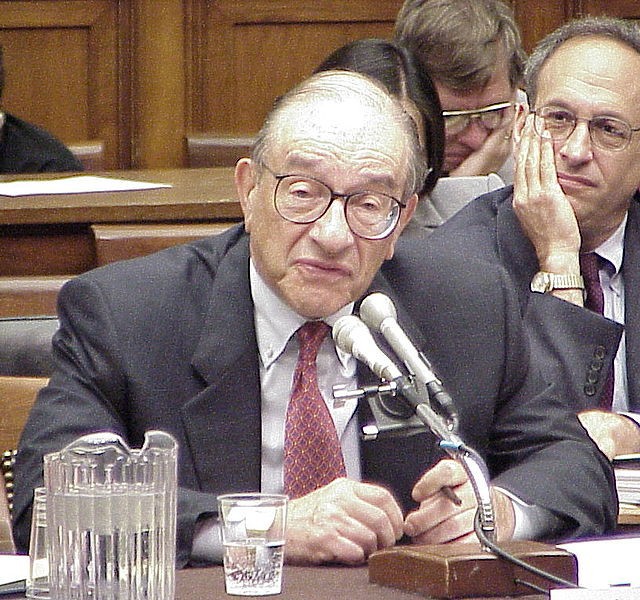

In his own way, Greenspan had inherited in toto Rand’s short-sightedness, egocentrism and complete lack of understanding of “the behavior of individuals and societies.” Though he would play his delusions out in a very different arena and not, so far as is generally known, be going around slapping anybody in the foyer. His big scene would come forty years later, in a Congressional hearing room.

Greenspan was no mere theorist when it came to Objectivism and was, in time, in a position to put its theories into practice on a massive scale. He believed fervently that business should not be regulated by us parasitic consumers, and had written to that effect from the ’60s onward. In 1987, he became Fed Chairman, succeeding the towering (and wholly unobjectivist) Paul Volcker. The results of his Objectivist convictions, made manifest in that role, were far-reaching. It has been argued in many quarters that Greenspan’s rock-ribbed laissez-faire policies resulted in a succession of bubbles — first in the dot-com boom, then in real estate and credit — that led directly to the 2008 crisis.

Part of the blame lies in his attitude toward derivatives. The efforts of the CFTC’s Brooksley Born to compel the regulation of derivatives trading began in 1994, but came to nothing owing largely to Greenspan’s objections. After the Enron debacle, which, thanks to “the smartest guys in the room,” left California holding the bag on about $9 billion of natural gas bills, Senator Diane Feinstein made herself very busy pestering Greenspan about the need to regulate derivatives. In 2004, Alan shrugged: he wrote to Congress in response to Senator Feinstein in what had by then become the signature Greenspan style of floaty, oracular, narcoleptic polysyllables:

Businesses, financial institutions, and investors throughout the economy rely upon derivatives to protect themselves from market volatility triggered by unexpected economic events. This ability to manage risks makes the economy more resilient and its importance cannot be underestimated. In our judgment, the ability of private counterparty surveillance to effectively regulate these markets can be undermined by inappropriate extensions of government regulations.

If the Enron disaster had not already made the hollowness of this argument horribly apparent, the financial crisis four years later could leave no doubt. And so it was that in October 2008, the mother of all Objectivist reckonings came to pass: The Span had to defend his disastrous policies to Congress one Thursday afternoon and explain why the U.S. economy, for decades under his stewardship, had gone kablooey. Here is what he said to that mob of furious congressmen who made up the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

“I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such as that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms […]

“Those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders’ equity, myself included, are in a state of shocked disbelief.”

Never mind that for years Greenspan had had a bunch of regulators and congressmen all but coming after him with baseball bats trying to get him to see that “the self-interest of lending institutions” was no match for the greed of unscrupulous individuals.

For Communist “altruism,” read “SEC regulation.” For Stalin, read Lloyd Blankfein et so many al. Just follow the money. How much does it cost such guys to pay lip service to the glories of the free market, Communism, whatever, while they grab everything that isn’t nailed down for themselves? Not too much, if all you care about is your own, um. Individualism.

“You had the authority to prevent irresponsible lending practices that led to the subprime mortgage crisis. You were advised to do so by many others,” said Representative Henry A. Waxman of California, chairman of the committee. “Do you feel that your ideology pushed you to make decisions that you wish you had not made?”

Mr. Greenspan conceded: “Yes, I’ve found a flaw. I don’t know how significant or permanent it is. But I’ve been very distressed by that fact.”

He found a flaw! I bet Diane Feinstein popped an aneurysm right then and there.

If Alan Greenspan had had a lick of sense he would have known that the jig was up and it was time for him to say, Ayn Rand was the biggest dope on record, except for me, because I listened to her. But guys like Greenspan don’t ever seem to say that sort of thing. I suspect that it’s because they have gotten so completely used to thinking of themselves as the “elite” who needn’t reckon with the “weak” objections of lesser men.

So Greenspan maintained his convictions to the last. Even in 2008 with the shit engulfing the fan, he was still trying to prevent more stringent securities regulation. Why?

“Whatever regulatory changes are made, they will pale in comparison to the change already evident in today’s markets,” he said. “Those markets for an indefinite future will be far more restrained than would any currently contemplated new regulatory regime.”

Using the exact same reasoning he’d just admitted to be erroneous, he was still claiming that the market would take care of itself. He found a flaw and then he lost it again pretty much instantly. The remains of the market are sitting right in front of him in a smoking ruin and what is his prescription? More of the same!

And what is the result, three years later? The markets in unregulated derivatives, Warren Buffett’s “financial weapons of mass destruction,” were never outlawed and are alive and well. Nobody went to jail or even really had his hand slapped, except for Bernie Madoff. Nearly all the destructive forces Greenspan set in motion came roaring right back, along with Wall Street bonuses, despite his claims of the enormous restraint certain to follow the debacle of 2008, for “an indefinite future” that didn’t last for even one year.

So here we return to the “looters” who don’t create anything, and the policy of cherchez l’argent. Greenspan and all these free marketers and bankers and Wall Street guys who generally just love Ayn Rand, self-sufficiency and individualism, and so they would never see themselves as the looters. But the question is just so there, because while the financial services sector provides some valuable services to a society, it is very questionable indeed whether those services are worth 12% of GDP, which is, by the way, about what we’re all paying now, or roughly triple what they used to cost before the publication of Atlas Shrugged.

The real parasites, it turns out, are not the looting masses but the Objectivist elites (what is it that these hedge fund managers “create” again?), rabidly pursuing their own “happiness” at the cost of our social safety net, our environment and the prosperity and well-being of the world’s people. So much for the triumph of individualism.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like A Gentleman, Think Like A Woman.

Alan Greenspan’s Federal Reserve portrait and photo of Greenspan testifying before Congress both via Wikimedia commons.