Chris Kanyon's Doomed Quest To Be Wrestling's First Openly Gay Star

by Thomas Golianopoulos

Chris Klucsarits’s night was off to a rough start. Backstage at the New York Wrestling Connection Sportatorium in Deer Park, Long Island, Klucsarits was involved in a conversation that could only happen backstage at a professional wrestling event: He was arguing with a promoter about using a giant towing chain during his match. He also insisted on carrying a crystal-skull goblet with red Kool-Aid to the ring. Earlier in the afternoon, he’d been meticulously stacking random objects — photographs, lumber — over and over again, and to cap it off, he was having trouble sewing on his wig. In short, Klucsarits was having a manic episode.

“He was out of his mind,” said Jim Mitchell, Klucsarits’s former wrestling manager. “He was bouncing off the walls. If you didn’t know any better, you would think he was on methamphetamine.”

On this night, Klucsarits would wrestle under a mask as “Mortis,” his gimmick from when he first made it big in the late 1990’s. Back then, Klucsarits — professionally known as Chris Kanyon — was a rising star in the now-defunct World Championship Wrestling, a promotion Ted Turner used to own. He was an innovative worker and the company’s go-to guy for training celebrity carpetbaggers such as Karl Malone and Jay Leno for their one-off cash-in Pay Per View appearances. Klucsarits was also making a go of it in Hollywood and worked as stunt coordinator for the David Arquette wrestling film Ready to Rumble. “I love Chris Kanyon. He was an amazing teacher,” said Arquette. “He taught me the little that I know on pro wrestling — how to take a bump, sell a move and conduct an interview. He was a true pioneer in his world.”

Now, Klucsarits scuttled on the independent scene, desperate for his old job back. World Wrestling Entertainment had fired him back in 2004, and here he was, six years later, in the minor leagues of professional wrestling. It was a scene straight out of The Wrestler, and the performers were a blend of townies, rookies and has-beens. Klucsarits now also had short hair. Which was a problem.

In the locker room, Klucsarits begged for help — he thought his costume would look completely ridiculous without the wig. He eventually attached the hairpiece and slipped on his red mask over it. The giant towing chain stayed behind but Kanyon carried the Kool-Aid-filled crystal-skull goblet with him and went to hit the ring.

Where everything came undone — starting with the wig.

Minutes into the match, Klucsarits threw a punch and with it, his wig dipped and shrouded his eyes, making him look like Cousin It. The crowd howled.

The laughter derailed him and he wrestled a sloppy match. Klucsarits won the bout but the bizarre behavior continued unabated. He drank from the goblet and posed dramatically with fans. He then broke character and screamed for the sound crew to play “The Lonely Man,” the closing theme from “The Incredible Hulk.” The wrestlers backstage were stunned. “Nobody wanted to say anything,” Mitchell said. “Everybody saw this guy as someone having a mental breakdown.”

Later at the hotel, Klucsarits announced he wanted to kill himself. It wasn’t the first time. Back in 2003, he had downed a bottle of sleeping pills. Now his manager attempted to console him. “I talked him through it,” Mitchell said. “He said, ‘No, all you people are being selfish. My parents tell me they are going to be heartbroken. My brother tells me he is going to be heartbroken. What about me? What about my fucking feelings?’

“That night, he told me it was a matter of ‘When,’ not ‘If.’”

Chris Klucsarits descended into one of the more sad and spectacular flameouts in the history of a business filled with sad and spectacular flameouts, and on April 2, 2010, he committed suicide at his apartment in Sunnyside, Queens. Friends said that an empty bottle of the bipolar medication Seroquel was beside him. He was 40.

Chris Klucsarits was a New York City kid from Sunnyside, whose life was defined by his struggle with his sexuality and his obsession with professional wrestling. He wasn’t much of an athlete growing up but he hit the gym regularly, filled out his lanky 6’4” frame and dreamed of following in the footsteps of his childhood idols, “Nature Boy” Ric Flair and “Rowdy” Roddy Piper.

He made the rugby team at SUNY-Buffalo and graduated with a degree in physical therapy but couldn’t shake the wrestling bug. “I actually tried to discourage Chris. I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be better if you just stayed as a physical therapist?’” said Robert “Bobby Bold Eagle” Cortes of the Lower East Side Wrestling Gym. Klucsarits reportedly earned $65,000 a year as a physical therapist. “He gave me a dirty look and said, ‘What are you crazy, Bobby? I love wrestling.’”

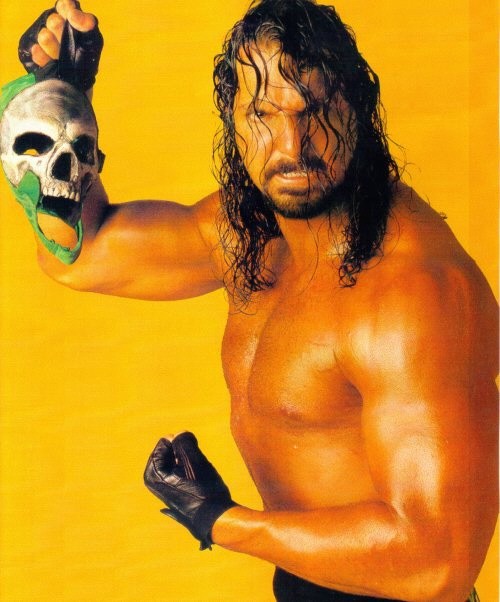

He then moved south, wrested in South Carolina and Memphis and got his big break after signing with the Atlanta-based WCW. Klucsarits wasn’t the most charismatic guy but he spent hours devouring wrestling tapes from around the world, trying to discover any obscure and spectacular wrestling hold. The hard work paid off. In 1997, Klucsarits debuted as “Mortis” — a character that was essentially a rip-off of the popular Mortal Kombat video games. It was a goofy premise and Mortis didn’t connect with fans but his in-ring work was stellar. “In spite of how ridiculous the gimmick was,” said his WCW trainer Jody Hamilton, “Chris came close to getting the character over simply because he did some new moves that people hadn’t seen.”

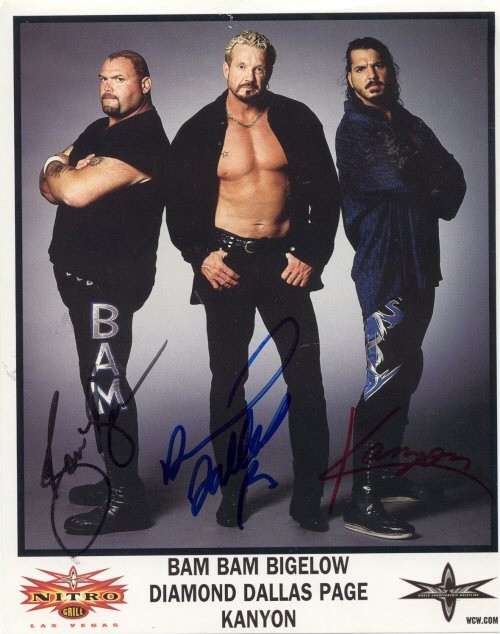

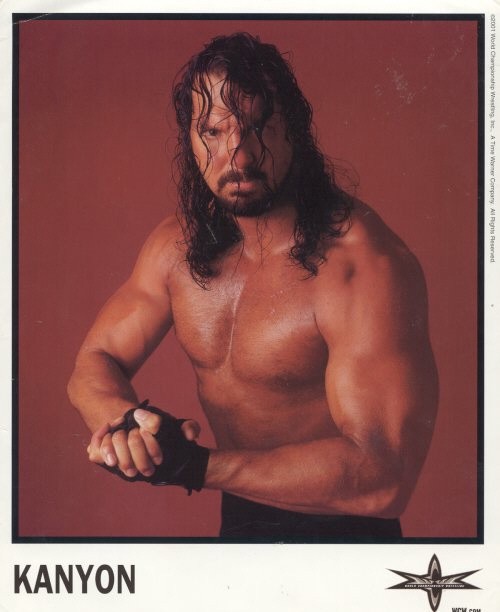

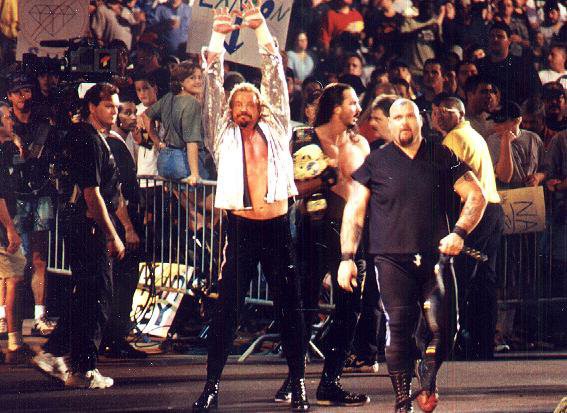

Once unmasked, he was billed as “Chris Kanyon” and sparkled in the middle of the card — his lisp and the rotating carousal of bad gimmicks hindered his chances at being in the main event. “He wasn’t going to make it as the top guy but he was one of my favorite people to work with,” said three-time WCW Heavyweight Champion Page “Diamond Dallas Page” Faulkenberg. “One of the curses of being a good worker is that they will put you with other guys to make them look good.”

That didn’t seem to bother Klucsarits. His friends said that he was proud of how his career was going. His biggest concern, however, was hiding his sexuality. Klucsarits discovered he was gay after kissing a girl when he was eleven years old. “There were no fireworks,” he later said. “I [then realized] that I would be gay for the rest of my life and that my life would not be easy.”

He first hooked up with another guy — a random teenager he met in a park — when he was seventeen. But after messing around by the monkey bars, Klucsarits told him not to come near him ever again. Later on, the Internet made hook-ups easier, but Klucsarits never had a serious boyfriend or felt comfortable in the gay community. “He didn’t really like gay people,” said his friend Robert McLearren. “He liked ‘straight-acting’ gay people.”

Klucsarits fit perfectly within the hyper-macho world of professional wrestling. He went boozing with the boys after events and even flirted with women. “He actually had sex with the girls,” said his friend Mike Passariello.

Jim Mitchell was one of the first people he came out to. “It was only because his cousins caught him with some gay pornography. They were helping him move and some gay porno fell out of a suitcase. He panicked so he had me call his cousins and pretend that I had ‘left something of mine with him.’”

Klucsarits eventually came out to his family about ten years ago. He first confided in his older brother, Ken and had him tell their parents. He informed most of his friends over AOL Instant Messenger.

At this time, Klucsarits was wrestling for WWE after they bought WCW in March 2001. He had some initial success, holding the United States title and Tag Team title, but WWE brass allegedly weren’t fans of his innovative move-set and overall wrestling style. Then came the injuries. In October 2001, he tore his anterior cruciate ligament and he was later hospitalized with a staph infection in his left bicep. One night, his lungs filled with fluid and life-saving emergency surgery was performed. He spent two weeks in the hospital and lost thirty pounds.

Klucsarits didn’t return to WWE television until February 13, 2003. During a bizarre segment, Klucsarits emerged from a large box (or, better yet, a closet) dressed like Boy George and sang “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me?” to his old rival, The Undertaker, before attacking him. The Undertaker got the upper hand and annihilated Klucsarits with a steel chair; the final chair shot legitimately knocked him unconscious. Klucsarits later said that he was instructed by a WWE employee to “sing like a faggot.”

In the preceding weeks, Klucsarits floated the idea of coming out as the first gay professional wrestler. “I wasn’t 100% sure if that was a message from [WWE Chairman] Vince [McMahon] for me to NOT come out of the closet,” Klucsarits later wrote on his MySpace blog. “So I continued to pursue the idea, hoping to get a verbal answer from Vince.” The Boy George incident was his last major appearance on WWE programming. He was demoted to the WWE’s B-level shows and fired in February 2004.

Klucsarits then retired from wrestling and lived as an out gay man in Florida. He said in an interview with outsports.com that “his sexuality was the cause of my depression, the reason I attempted suicide.” During later treatment, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

During the brutal “lows,” Klucsarits would often stay in bed for days. At times, he lost touch with reality. “Chris believed in parallel universes,” McLearren said. “He believed he died in one universe. After that night his lungs filled with fluid, he had no [wrestling] career and to him, that meant his life was over. I remember he called me and asked, ‘How long have I been dead?’ He was standing outside a facility in New York, ready to commit himself because he was so out of control at that point.” In an effort to regain control, Klucsarits plotted a comeback.

During his career, Klucsarits portrayed a masked Thai fighter, a grungy cult follower and a deranged stalker. In real life though, Chris Klucsarits was a gay man who believed that he might have lost his job because of his sexuality. He decided that Chris Kanyon should be that same guy.

In February of 2006, he came out at an independent wrestling show in Sudbury, Ontario. The crowd was confused, as were the wrestlers. “Some guys wondered if it was a work, you know, a storyline,” said Chris “Cody Deaner” Grey. “Wrestlers think everything is a work.”

After coming out in Sudbury, Klucsarits wrote a press release stating that “Chris Kanyon” the character was gay. It was meant to create interest from WWE and Total Nonstop Action, a new Orlando based promotion: The plan was to sign a new contract and come out on national television. Both promotions passed.

“We always try to give former talent second looks,” WWE spokesperson Robert Zimmerman said. “We felt like he had a limited skill-set at best for the job. Because of that, we wouldn’t hire him back.”

Klucsarits came out as “himself” at an independent Pay Per View event a month later. He believed WWE and TNA missed out on a groundbreaking and potentially popular angle. “I have absolutely no doubt that you could get a positive gay role model over in pro wrestling,” said Barry Alvarez, editor of the wrestling newsletter Figure Four Weekly. “It wouldn’t be easy. I don’t want to say wrestling fans are set in their ways but they aren’t always progressive.”

Professional wrestling has a dubious track record with minorities. If a performer has any accent, then, naturally, he’s an evil foreigner. Homosexual gimmicks pandered to even uglier stereotypes. Past acts such as Adrian Adonis, Billy and Chuck, the West Hollywood Blondes and Orlando Jordan, an open bisexual currently employed by TNA, wore make-up, pink ring tights and used their “sexuality” to garner cheap heat from fans.

Klucsarits aspired to portray a tough guy that just so happened to be gay. And in this world of Prop 8, Carl Paladino, the gruesome “Goonies” attacks in the Bronx and the Tyler Clementi suicide, Klucsarits could have had a positive impact.

“He wanted to be a role model for people in the closet,” Grey said. “He wanted to set an example for teenage boys that were struggling with their sexuality and were being teased.”

Klucsarits made one last gasp at getting rehired. On September 8, 2006, he attended a WWE event in Tampa, Florida and held up signs directed at WWE stars Triple H and Shawn Michaels. They read, “HHH please ask Vince why he really fired me” and “Shawn, please pray for my gay soul.” He was eventually ejected from the building.

“He thought he was creating controversy in hopes of coming back,” said McLearren, who also claimed Klucsarits was in e-mail contact with WWE Executive Vice President, Stephanie McMahon. “Chris said that Stephanie gave him the go-ahead to do whatever he wanted. I think she [thought], ‘You are not employed here. You can do whatever you want.’ And he [thought], ‘[Go] build the storyline.’”

That fall, Klucsarits found a soapbox to lash out at WWE on “The Howard Stern Show.” He burned his final bridge with the company when he joined former colleagues Mike Sanders and Scott “Raven” Levy in July 2008 and sued WWE, challenging the long-held practice of categorizing wrestlers as independent contractors. “It seemed like he had a lot of anger built up inside him about how he was portrayed in WWE,” Mike Sanders said. The lawsuit was soon thrown out because the statute of limitations had run out.

Alienated from the business he loved, Klucsarits was crushed. He lost contact with friends, only rarely communicating through text message. Still, he sought help. Klucsarits researched LSD treatment for bipolar disorder and took anti-depressants — but not consistently.

He also contacted Christopher Nowinski, a retired former professional wrestler and now co-director for the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University School of Medicine. Klucsarits claimed that he suffered at least twelve concussions during his career and believed they contributed to his depression.

“There is a disease called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy where depression can be a symptom,” Nowinski said. “We’ve diagnosed [people] post mortem with CTE who were [originally] diagnosed with bipolar [disorder]. Considering the rate at which we are diagnosing athletes with CTE who have had similar brain trauma exposure, I would not be surprised if Chris was suffering from CTE when he passed away.”

“Chris went from a happy adjusted guy to someone who clearly suffered from brain damage,” Passariello said. “Watching him deteriorate over those years was very painful.”

In his last days, Klucsarits worked as an insurance agent and returned to physical therapy. He didn’t last long at either gig. “He lost all his confidence in his abilities because he hadn’t done it in so long,” McLearren said. “He was just overwhelmed.” He also dreamed of opening a wrestling school in Sunnyside but it didn’t get past the planning stages

His friends don’t know what pushed Klucsarits over the edge — they mentioned problems with the IRS, looming eviction and Medicaid cuts.

On April 7, 2010, at a funeral home on Queens Blvd, Chris Kanyon action figures covered a table. Bobby Bold Eagle was one of many former and current professional wrestlers at the wake. He huddled with Klucsarits’s parents.

“We had a good cry,” he said. “I told the dad, ‘Look man, I’m sorry I trained your kid for this business. Just don’t hate me, man, because that’s [all] he wanted.’”

Thomas Golianopoulos is a writer living in New York City whose work has appeared in The New York Times, New York Observer, Spin, Vibe and a few other places. You can follow him on Twitter.

Photos from the collection of Robert McLearren.