Angry Words: Let's Restore Honor To Online Scrabble

by Reeves Wiedeman

The word “quale” is a noun. It comes from Latin, rhymes with Pixar’s robot, and means, most commonly, “the quality of a thing.” For instance: the particular redness of a particular McIntosh apple. According to the OED, this usage first appeared in 1675, then again in 1875, which, as far as I can tell, was also its last usage. Or it was, until a few weeks ago, when a friend of mine earned 32 points by playing the “e” on a Double Word Score in a game of the Scrabble-simulator “Words with Friends.”

More than ten million people have downloaded “Words with Friends,” and many others play similar versions: Facebook Scrabble, Pogo, Lexulous. The game feels more refined than flinging birds from slingshots and is best enjoyed, as its name suggests, with people you know. I play against friends, family and co-workers in California, Missouri and Massachusetts, and, in many cases, the game has become our most frequent contact.

In short, we’ve entered a New Age of Electronic Scrabble — a Golden Age, even, bringing together former roommates, mothers and sons, friends and long-distance lovers. But there’s a dark side to “Words with Friends” — a nefarious quale, if you will — that represents the greatest smartphone-induced threat to our nation’s integrity since the Blackberry ruined pub trivia. It appears in the form of “zax” or “hame” or “henting,” each of which are underlined in red as I type this in Microsoft Word, and each of which have been successfully deployed against me in “Words with Friends.” And I’m certain that when my opponent played “hame,” she was as surprised as I was to find that the word existed.

In short, the problem we face is an epidemic of guessing. Unlike traditional Scrabble, where you can demand, on the spot, that your opponent find “zax” in the dictionary, “Words with Friends” opponents can be separated by zip codes, boroughs, even time zones. The game offers no penalty against guessing — it simply declines your attempt, politely encouraging you to try another improbable-but-high-scoring combination of letters. My friend “had a feeling” that “quale” was a word, so she guessed. Another friend played “zikurat” (45 points) before informing me that, of course, “ziggurat” has a number of alternate spellings. Admittedly, I’ve made a number of questionable plays myself.

Here’s a list of words that I’ve seen used in recent games, with accompanying definitions adapted from the OED:

• Arf — in certain dialects, a form of “argh”

• Dungs — to cover with manure

• Gar — a fish with long bill-like jaws

• Haled — to pull (past tense)

• Heeder — a male sheep from nine months old to its first shearing

• Malfed — no OED entry!

• Quod — to put in prison

• Varve — “a pair of thin layers of clay and silt of contrasting color and texture which represent the deposit of a single year (summer and winter) in still water at some time in the past (usu. in a lake formed by a retreating ice-sheet)”

• Yar — to snarl, as or like a dog

• Zona — “zone,” if you’re an anatomist

Each of these appears in something called the Enhanced North American Benchmark Lexicon, or, ENABLE, a public-domain dictionary used by “Words with Friends” to determine which words count and which don’t. I’d guess that many words on this list are beyond most players’ vocabularies — and yet online Scrabble creates an irresistible scenario where we play words we don’t even know.

Scrabble, it seems, has met its steroid problem, with its own competitors threatening the game’s integrity under the banner of, ”Well, everybody’s doing it.” Chalk this up to the Internet enabling (remember the dictionary’s acronym?) yet another flaw in human nature. So, until the overlords of “Words with Friends” institute a penalty for guessing, something must be done. To that end, I propose all players abide by a simple honor code: For words of three or more letters¹, you should be able to offer a definition.

It’s impossible to enforce, of course. But try we must. Otherwise, what will we do if, God forbid, we somehow find ourselves playing a real-life game of Scrabble against a real-life opponent? Skills atrophied, will we just stare blankly at our tiles, wondering if “Phrzk” might possibly be a word?

¹ The use of two-letter words opens up so many layers of Scrabble strategy that it would be foolish to require anyone to know that “jo,” “aa,” and “ka” are defined, respectively, as a Portuguese coin, a stream, and the “name given by the ancient Egyptians to a spiritual part of a human being or a god which survived after death and could reside in a statue of the dead person.” Thus, they’re fair game.

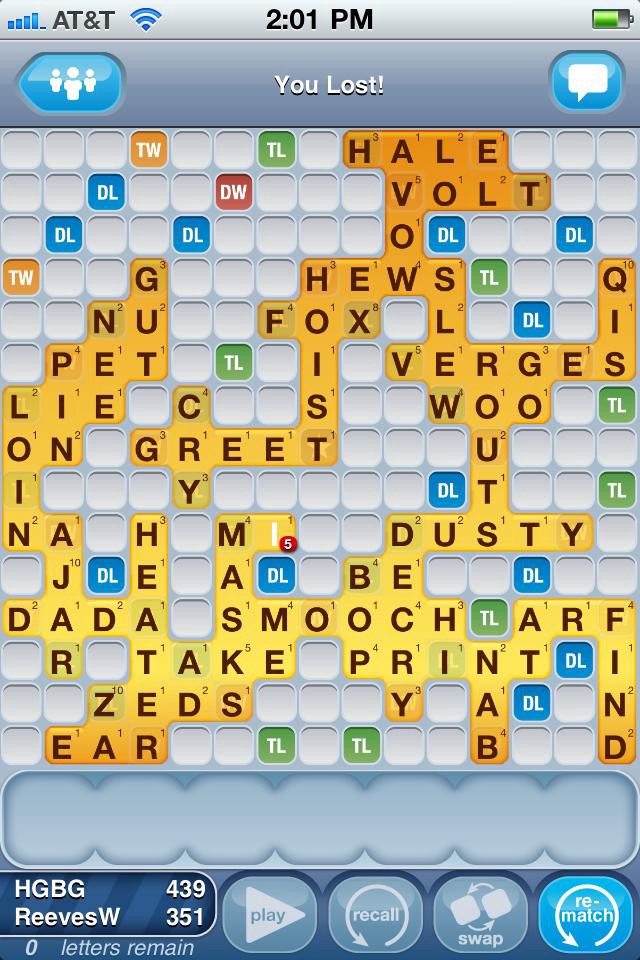

Reeves Wiedeman plays “Words with Friends” under the name ReevesW. He welcomes all honorable competitors.