The New Decemberists Album: It Contains 100% Less Raping

by L.V. Anderson

The Decemberists’ new album, The King Is Dead, takes the band in a new direction: tamer, more pastoral lyrics and a pared-down, bluegrass-tinged sensibility (with guest vocals from the always-excellent Gillian Welch). Critics have taken note, and the reviews have been mostly positive — people seem relieved by the band’s turn away from the melodramatic subject matter and overwrought musical stylings that have characterized their last couple albums. But the most notable difference from the band’s older music — and one I’ve yet to see a critic mention — is that there’s not a single rape or abduction to be found on the entire album.

I started listening to The Decemberists eight years ago, when my sister, C., came home from college one winter break with their first two full-length albums, Castaways and Cutouts and Her Majesty The Decemberists in her car stereo. C. felt partially responsible for my musical education, and she played the albums for me over and over for weeks as we drove around our mid-Atlantic suburb.

There were some things I liked a lot about The Decemberists. Their lyrics were literary, cosmopolitan and full of big words, all of which appealed to my inner aspiring snob. They had a song called “Odalisque”! And another called “Song to Myla Goldberg”! I didn’t know what an odalisque was, or a Myla Goldberg, but I wanted to be the kind of person who knew these things. They had a way with driving chord progressions, unconventional instrumentations (accordion, organ, glockenspiel) and unexpected harmonies that were fun to try to sing along to. Their one strummy love song, “Red Right Ankle,” seemed to speak directly to my lonely, stupid, young heart and the type of passionate affairs it hoped someday to have. But there were also things I wasn’t so sure about.

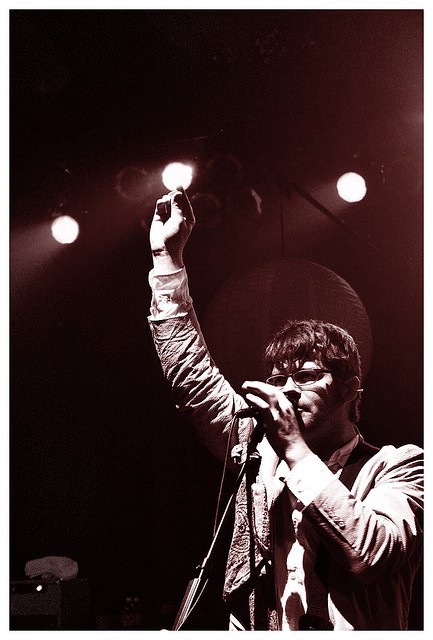

For one thing, their lead singer, Colin Meloy, sounded like a British goat. No, wait; that’s not quite right, and I want to get this right: Think of Morrissey’s morose drone, and combine that with the nasal mewl of Blink-182’s two lead singers. And NOW imagine that sound coming from a goat. Voilà!

The main thing that weirded me out about The Decemberists, however, was not Colin Meloy’s voice but the fact that his lyrics could be dark. And not dark in an Elliott Smith or Fiona Apple way — the way a solipsistic, depressive teen could curl up in bed and sob about the UNFAIRNESS of it all while listening to — but frighteningly dark. There was one song in particular I couldn’t bear to listen to: “A Cautionary Song” on Castaways and Cutouts, a three-minute sea shanty about a single mother who prostitutes herself to a gang of hostile sailors in order to make enough money to feed her young children.

“I hate this song,” I whined to C. as we drove to the mall to exchange sweaters our parents had given us for Christmas. (She wouldn’t let me skip the track — driver outranks shotgun when it comes to music privileges, obviously.)

“It’s supposed to be ironic,” she said, rolling her eyes at me.

She was right: It was supposed to be ironic. In fact, irony was the entire point. The Decemberists’ juxtaposition of old-fashioned language with disturbing themes is what has endeared them to so many listeners since their formation in 2000. They’ve enjoyed critical and increasing popular success over the years, to the extent that The King Is Dead debuted at the top of the Billboard Top 200 in January. (A recent New Yorker Talk of the Town story depicts the band as deliberately nonchalant in learning the news of their album’s success.)

You can count me among the many fans who have turned The Decemberists from an anonymous prog-rock group from Portland into something close to a household name. Not wanting to be insufficiently appreciative of irony, I pushed past my initial squeamishness that winter break and soon came to genuinely love The Decemberists. I bought every one of their subsequent albums. I listened to their uptempo songs as I went running in the morning and their downtempo songs as I drifted off to sleep at night. I talked about them with boys I had crushes on and saw our mutual interest in the band as a sign of how RIGHT we were for each other.

I got so close to The Decemberists’ music that I stopped even noticing the violent misogyny that had initially given me pause. But that misogyny wasn’t an isolated incident; on the contrary, it’s a major theme of the band’s work. During the eight years since Castaways and Cutouts came out, The Decemberists have repeatedly abducted, raped and killed women, and their well-educated, liberal fans and critics have lapped it up.

Let’s take a closer look at “A Cautionary Song,” which, though only three minutes and nine seconds in length, feels like it will never end when you are listening to it. The song is, on the surface, a grotesque children’s story: an exaggerated version of what you might tell a particularly bratty kid if you wanted to scare the shit out of him. It begins with a sing-songy taunt — “There’s a place your mother goes when everybody else is soundly sleeping” — and then goes on to describe the indignities your mother is subjected to. Here’s a sampling of lyrics, written (as are all The Decemberists’ songs) by Colin Meloy:

With dirty hands and trousers torn they grapple ’til she’s safe within their keeping.

A gag is placed between her lips to keep her sorry tongue from any speaking, or screaming,

And they row her out to packets where the sailors’ sorry racket calls for maidenhead.

And she’s scarce above the gunwales when her clothes fall to a bundle and she’s laid in bed on the upper deck.

I see the irony now — but it’s not a particularly profound irony. The song’s tone is certainly sardonic enough, and the combination of old-fashioned poetics with a violent subject matter is joltingly incongruous. But beneath Meloy’s dense, wry language, “A Cautionary Song” is little more than a three-minute yo-mama joke, with the extra thump of an unexpected punch line: “So be kind to your mother, though she may seem an awful bother, and the next time she tries to feed you collard greens, remember what she does when you’re asleep.” (Ba-dum-bum!)

This punch line is actually kind of funny, if you have a dark sense of humor. But somehow… not really funny enough to warrant setting a poem about a systematic gang rape to jaunty accordion music. To me, anyway.

And Colin Meloy claims to understand that. He declined via a publicist to be interviewed for this article, but he spoke about his use of rape imagery in a 2006 interview for Venus Zine with Ann Friedman, Feministing.com blogger (and Awl contributor). When Friedman asked whether he considered how his lyrics come across to female listeners, Meloy responded, “These are touchy subjects. … It’s something I consider very strongly as a songwriter. There’s a lot of touchy subjects we deal with — not only rape and violence, but racism, anti-Semitism. I know it’s so loaded, being a male and singing about these things. I don’t do it aloofly, but there’s a reason why I’m pushed to write about these sorts of things. The tone of these songs is supposed to be really dark.”

He then added: “When you’re writing in the voice of a character, it doesn’t seem genuine to rope yourself off. … In some sense, not only am I trying to adopt an appropriately dark tone, but also staying true to the genre.”

Yet the record belies Meloy’s claims of addressing the subject with “an appropriately dark tone.” If you have a few minutes, watch this clip of Meloy performing “A Cautionary Song” in Portland in 2008:

When he gets to the “sailor’s sorry racket calls for maidenhead” part (about 0:55), he cocks his hand behind his ear and leans expectantly towards the crowd. They whoop, laugh and applaud.

“Will somebody just yell ‘maidenhead’?” he asks the crowd, laughing.

“MAIDENHEAD!” they dutifully roar.

Can we imagine, for a moment, what this song would be like if Meloy hadn’t couched it in elaborate language and a pseudo-historical setting? Suppose “A Cautionary Song” were set in a modern-day housing project or a trailer park instead of a 19th-century port city; suppose Meloy asked the crowd to yell “PUSSY!” instead of “MAIDENHEAD!” Do you think The Decemberists would be able to get a crowd of pretentious white indie kids in Portland to cheer and clap for that song?

I doubt it (although, who knows? kids these days, etc.), and so does Meloy. In a 2003 interview, Meloy said of his rape-themed songs, “I think when you put them in the context of something in the 19th century, you’re still addressing it, but it takes on a different feel. There’s a whole different world that it’s creating.” Meloy seems to acknowledge that the joke of “A Cautionary Song” wouldn’t work with modern-day language and modern-day characters, even if the brutality and punch line stayed the same. If you took away the anachronism and the quaint language, there wouldn’t be much left except for — well, rape.

I am sorry to report that your mother is not the only victim of misogyny in The Decemberists’ libretto. In the band’s first five albums, several female characters meet unfortunate fates, including (in chronological order):

- dying in childbirth and then haunting a catacomb for the next fifteen years along with the premature infant’s ghost (“Leslie Anne Levine,” Castaways and Cutouts)

- being enslaved, raped, and beaten, and possibly dismembered, depending on how you read the lyrics (“Odalisque,” Castaways and Cutouts)

- being beaten and raped in the middle of nowhere following a miscarriage (“The Bachelor and the Bride,” Her Majesty The Decemberists)

- being coerced into sex by a man of means and then, after his disapproving parents find out, being coerced into a suicide pact with him (“We Both Go Down Together,” Picaresque)

- being seduced by a rake with a gambling problem, being saddled with his debts after he leaves, and dying of consumption (“The Mariner’s Revenge Song,” Picaresque)

- being abducted on the beach at pistol- and saber-point, and then being raped and killed (“The Island,” The Crane Wife)

- being kidnapped, tortured, and — wait for it — raped by a sociopathic child-killer (“Margaret in Captivity,” Hazards of Love)

There are a lot of “being”s in that list, because women in Decemberists ballads rarely play an active role in their own stories. They’re usually tabulae rasae; we get no sense of their personal experience or their individuality. They often show up out of nowhere for the express purpose of dying in order to advance the plot of the song. Not one of these stories is told from the woman’s point of view; many of them are sung from the point of view of the woman’s rapist or murderer. (“Leslie Anne Levine” is sung from the point of view of the premature infant’s ghost.) (Really.)

It’s not that terrible things don’t also happen to men in Decemberists songs; to the contrary, the shit hits the fan for many of Meloy’s male characters, too: wretched chimney sweeps, suicidal coal salesmen, sailors who get swallowed by whales, dead Confederate soldiers. (Meloy’s big on the undead.) The difference is that the men in Decemberists songs are usually accorded first-person perspectives, feelings, motivations, internal lives — the whole real-person treatment. Meloy’s men are victims, yes, but they’re not just victims. They do things rather than simply having things done to them.

To his credit, Meloy doesn’t judge his ill-fated female characters. There’s never a sense that they have it coming to them or that they deserve their gruesome fates. (But, really, isn’t not being judged by her creator the least a character can ask when she’s being raped, beaten or drowned?) But that’s because he doesn’t judge any of his characters. Meloy is maddeningly detached from the narratives he spins and the characters he creates, but he doesn’t use his distance from his characters to say anything about them or their actions. His sadistic psychos just are sadistic psychos. His damsels in distress just are damsels in distress. Meloy isn’t saying anything about rape — he’s just saying “rape.”

The problem is that Meloy seems to think that his use of misogynistic themes is artistically and even morally justified. When asked about his interest in rape, kidnapping and murder in a 2009 AV Club interview, Meloy said:

I do think I have a particular interest in those tragedies for some reason. But I also felt vindicated and not so much like a sicko when I dug into a lot of the bigwigs of the British folk revival. People like Anne Briggs and Nic Jones and Sandy Denny and June Tabor, Maddy Prior. When you dig into their material, you see that there’s kind of a common fascination — a lot of the folk revivalists in England particularly are really into the darker material. And oddly enough, I think there’s something to be said to a lot of the women singers who are focused on the darker-bodied material. A lot of scary misogyny was present in a lot of early folk songs. And I think there’s an empowering sense, this idea of revisiting these songs in a contemporary context is a way of not only highlighting what it was to be a woman in the 16th, 17th century, but also how those sorts of scary, violent events were omnipresent in these folksongs as well.

So Meloy seems to have two main justifications for singing about raping and killing women, as far as I can tell:

- Women folk revivalists sang about rape as a way of empowering themselves, which makes it okay for The Decemberists to do it for the sake of “staying true to the genre.”

- Singing about violence against women reminds people how shitty life was for women before the mid-20th century.

Okay, first thing: Whom exactly is Meloy empowering by singing about rape and murder? I feel like this should go without saying, but empowerment via reclamation of historically hurtful themes isn’t really a transitive thing. Could female British folk-revival singers empower themselves by singing about rape? Sure! Can Colin Meloy empower women by singing about rape? No! Well, he can try, but it’ll go over about as well as if I tried to empower African-Americans by tossing around the n-word.

What’s more, there’s a difference between singing old misogynistic folk songs for the sake of historical remembrance and writing original misogynistic folk songs. The British folk revival “bigwigs” that Meloy mentioned in his AV Club interview don’t seem to have sung very many songs about rape, but that ones that they did sing — like Anne Briggs’s “Young Tambling” and Maddy Prior’s “Lass of Loch Royal” — were English and Scottish ballads that have been sung for centuries. To an extent, folk music is about preserving cultural traditions and historical texts, which is what Briggs and Prior did in recording these songs. Meloy’s songs are pseudo-historical, faux folk songs: original compositions that imitate the themes and subject matters of old ballads without any additional reflection on these themes.

Not to beat the sexism/racism equivalence into the ground, but Meloy’s argument that his use of misogynistic imagery is a way of “highlighting what it was to be a woman in the 16th, 17th century” holds up about as well as the claim that it wouldn’t be offensive for a white artist to write a brand-new minstrel show and perform it in blackface, because it reminds people how blatantly racist white Americans used to be. Reproducing old forms of oppression without commentary doesn’t challenge those forms of oppression; it perpetuates them. Writing original songs about violence against women for the sake of “staying true to the genre” of folk music isn’t brave or interesting; it’s gratuitous.

Gratuitous misogyny is nothing new in pop culture, or even in pop music — please see the many books and academic articles that have been written on the subject of misogyny in hip-hop culture. The Decemberists’ use of misogynistic images isn’t any worse than that of Ludacris or Dr. Dre, but it isn’t any better, either. So why has Meloy been largely spared the same hand-wringing and moralizing that have dogged hip-hop for literally decades?¹ Oh, right: He’s white; he has a bachelor’s degree in creative writing; he employs an expansive vocabulary and has a penchant for historicism and literary devices. The Decemberists’ music is hyper-literary, guys. It’s prog rock, so.

I should make it clear that I don’t think Colin Meloy is a misogynist. He may well be quite the opposite. But his justifications for telling stories about violence against women disregard the fact that his music functions primarily as entertainment. Regardless of Meloy’s artistic intentions, The Decemberists’ music creates a space where people who are normally constrained by political correctness — well-educated, politically liberal, upper-middle-class, mostly white people — can enjoy uncomplicated misogynistic fantasies. The Decemberists capitalize on people’s unspoken chauvinism, their inner animalism, and they send the message that it’s unproblematic — even empowering! — to enjoy misogyny, so long as you couch it in florid language and pseudo-historical settings.

And as long as you don’t really mean it. In that 2006 Venus Zine interview, Meloy said, “I’m not a misogynist. I’m not a rapist. I’m not an anti-Semite. People should be able to see there’s a sense of irony there.”

Funny thing about irony: It works best, I find, when there’s a message behind it. It’s hard to say the opposite of what you mean when you don’t mean anything at all.

¹ The one exception seems to be Conservapedia (“The Trustworthy Encyclopedia”), which describes The Decemberists as an “immoral, liberal, Indie-rock band from Portland, Oregon. … known for glorifying rape, suicide …, and various other sinful acts in their music.”

L.V. Anderson lives in Brooklyn.

Concert photos of Meloy by Oslo In The Summertime.