Here Are the Thousands Who Gathered to Thank Mubarak

by Christian Vachon

“It may be a small group,” said Sharif, a 29-year-old Coptic Egyptian, looking out the windshield of his BMW into the line of traffic that streamed down the highway in the mid-afternoon sun. “No station on television talk about this. I don’t know why — it’s not fair. All the stations are afraid of Tahrir.”

On this dusty highway, celebration was in the air. A flood of Egyptians were packed into flat bed trucks and traditional third world, go-cart passenger cars. Horns honked. Hands flashed victory signs out car windows. Alongside Sharif, three teenagers on a motorcycle sped between lanes. The center passenger held an eight-foot Egyptian flag high in the air, billowing as they rode. It was Friday and so most of these cars were headed to Tahrir Square, where hundreds of thousands were expected to attend the “Day of Victory,” a celebration of the 18-day standoff that dethroned a president and has shaken dictators across the region.

But at his steering wheel, Sharif’s face was somber. His eyes were fixed blankly on the road. He drove past the exit for Tahrir, continuing on to a counter rally for Mubarak supporters at the Moustafa Mahmoud Mosque in Mohandeseen City.

“My friends are afraid, maybe the people from Tahrir come here,” Sharif said. It was noon and a few hundred supporters had gathered outside the mosque. Securing the grounds were fifteen army infantrymen standing in a line across the distance. Wearing flack-jackets, with AK-47’s strapped across their chests, spaced six feet apart, the soldiers directed arriving cars to parking zones near the rally.

Three weeks ago Mubarak operatives were dispatched to assault, arrest, detain, intimidate and silence the international press. I experienced this personally when I was shot in the leg with a plastic round in a drive-by outside the Ramses Hilton. But in the midday heat, before the Mostafa Machmoud mosque, amid thousands Mubarak supporters — freedom of the press had never found more ardent champions. In the backdrop of chants and songs, flanked by banners of homage, reporters were surrounded by Mubarak loyalists, all eager to praise their leader and register dismay at the revolution that has made him the exile of Sharm el-Sheikh.

“His wife made a great project, with reading for all,” said Ranra, 27, a communications engineer. “Because of her, I love to read. She began a program. We could buy books for one pound [20 cents U.S.] She made hospital for children with cancer — the biggest in the Middle East.”

A 52-year-old woman stood cradling the framed portrait of her 19-year-old son, Abanoub Kamal Nashed, one of the eight Copts murdered leaving New Year’s services in the Nag Hammadi massacre of January, 2010. Asked what brought her out to Mohandeseen she replied with bitterness: “They are against our culture with their disrespect of our president.”

“Everyone loves Mubarak,” an elderly woman said, dabbing the tears from her eyes. “We hope he comes back to us.”

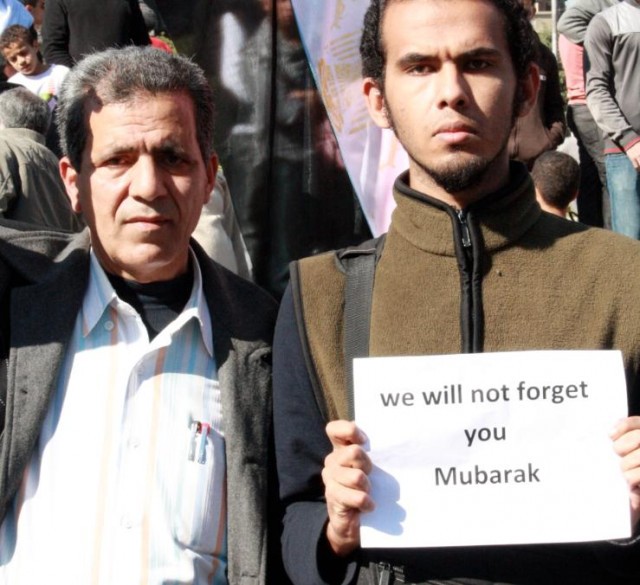

In the crowd, supporters held posters of the dethroned. There was Mubarak the young, slim air force commander, standing confidently beside Sadat; Mubarak the diplomat in Ray Bans and European suits; Mubarak the tired and aged with slicked back dyed hair, Botoxed forehead and pruned eyes.

If the gossip swirling through Cairo’s elite circles is to be believed (and the city runs on such gossip), the final face of Hosni Mubarak can be found in Sharm el-Sheikh, where the leader has fallen into a coma, refusing to take the medications that manage a myriad of health conditions related to his bout with pancreatic cancer.

He is there with Alaa, the one-time prodigal son who became a devout Muslim after losing his child to a heart condition. There are reports that on the night of Mubarak’s confused final televised address (it’s widely believed that he fainted during tapings) the Mubarak brothers had to be pulled away from each other after Alaa accused the younger Gamal of ruining his father’s legacy by appointing corrupt associates to influential ministry and cabinet positions in the NDP.

The names and biographies of Gamil’s appointees are well known across Egypt. Among them are Anas El Feky, Minister of Mass Media (and one time lead singer of the Egyptian rock band Riddle); Safwat El Sherif, a head of the congress found guilty of being a pimp in 1967; Ahmed Ezz, a close friend of Gamil Mubarak who controlled two-thirds of the Egyptian steel market (Egyptians torched his company three times during the revolution), leader of the parliament budget committee, and a former drummer.

By 2 p.m., two to three thousand Egyptians had amassed. Supporters formed a line along the back of a black main-stage, waiting to pay their final respects to Hosni Mubarak. At the end of each speech there was applause. After the applause came a few minutes of chanting the refrain, “Mubarak, the world and history will place you on high,” while the next speaker prepared their eulogy.

The messages were scattered and defiant.

One man drew a roar, screaming, “ Al Jazeera! All the people are here!”

A loud ovation came when a woman reminded the audience that “Mubarak would not let America build its military bases here!”

The crowd cheered when a woman suggested, “After this, we should all go to Sharm el-Sheikh and thank President Mubarak for all he has done!”

Standing in the back, away from the noise and the jeers, with arms folded across his round belly, stood a 51-year-old named Achmad.

“He’s a good man. He loves his country,” he said. “I am a diving instructor. I had a business in Sharm el-Sheikh and he came for a visit. It was 1983. I was very young and he had only four people security. It was very simple.”

“You know, he’s a pilot,” he said. “He explained that flying is similar to diving. When he left he said, ‘next week I will send you my sons, to teach them.’”

He did. “The next week he sent me Gamal and Alaa,” he said. “I taught them diving. Good guys. Very polite. They talked about sports. But we were young, so we talked about girls you know….”

Seven years later, in Hurghada, Achmad ran into Gamal and Alaa Mubarak again.

“They had a lot of security. I didn’t like it. They started to become big,” he said. “They were involved in business. I didn’t like the way they started to behave. They changed, like having big cars and talking high. And ten years after that I had a problem. I tried to contact them. I couldn’t get them.”

At center stage, a woman held a bundle of red, white and black helium balloons. The DJ cued one of Egypt’s patriotic hymns, “My Country.” The woman released the balloons. They floated away while the people clapped and sang along to the lyrics, “My country, my beautiful country, my sons and my daughters are for you.”

“God will protect Egypt,” Achmad said, watching the balloons drift away into clear blue sky, “The only thing I hope is that the army is not controlling us.”

Gordon Reynolds is the pseudonym of a teacher in Cairo. He also posts regularly to Twitter, if you follow him there.