Gladwell Won't Get It: The Real Role of Twitter in Global Protest

There was a lot wrong with Malcolm Gladwell’s super-ballyhooed piece, “Small Change,” in the New Yorker last October. In it, he suggested that the Civil Rights movement in the U.S. took place without Twitter or Facebook, because they hadn’t been invented yet. Now that the same questions have come up again with respect to recent events in Egypt, Gladwell hopped right onto the New Yorker blog to complain some more about how not-important Twitter is.

But surely the least interesting fact about them is that some of the protesters may (or may not) have at one point or another employed some of the tools of the new media to communicate with one another. Please. People protested and brought down governments before Facebook was invented. They did it before the Internet came along. Barely anyone in East Germany in the nineteen-eighties had a phone — and they ended up with hundreds of thousands of people in central Leipzig and brought down a regime that we all thought would last another hundred years — and in the French Revolution the crowd in the streets spoke to one another with that strange, today largely unknown instrument known as the human voice. People with a grievance will always find ways to communicate with each other. How they choose to do it is less interesting, in the end, than why they were driven to do it in the first place.

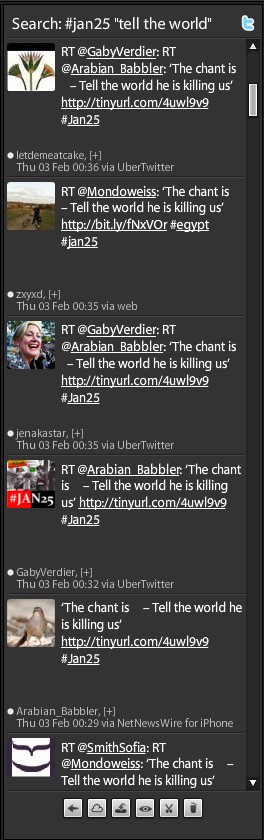

We are free to disagree with Gladwell over what is more or less “interesting” about the Egyptian uprising. But he has continued in one crucial misapprehension that is worth correcting: the Egyptian protesters are not just “using some of the tools of the new media to communicate with one another.” They are using Twitter to take their case outside Egypt; to document their own experiences truthfully and fairly, themselves, before governments and big media can get a chance to put their spin on everything.

Gladwell, from the original piece:

“It is time to get Twitter’s role in the events in Iran right,” Golnaz Esfandiari wrote, this past summer, in Foreign Policy. “Simply put: There was no Twitter Revolution inside Iran.” The cadre of prominent bloggers, like Andrew Sullivan, who championed the role of social media in Iran, Esfandiari continued, misunderstood the situation. “Western journalists who couldn’t reach — or didn’t bother reaching? — people on the ground in Iran simply scrolled through the English-language tweets post with tag #iranelection,” she wrote. “Through it all, no one seemed to wonder why people trying to coordinate protests in Iran would be writing in any language other than Farsi.”

Except that the significance of Twitter’s role in the Iranian uprising had nothing to do with coordinating the protests; it’s more efficient to arrange phone trees and email lists and go door-to-door for that sort of thing, I imagine, in Iran or anywhere else. Inexplicably, Esfandiari, and Gladwell after her, failed to note that the point of twittering the Green Movement was to get the word out to the broader world about what was going on in Iran. Despots may have free rein in their own backyards, but even they are capable of being exposed and shamed in the world outside. So it made sense for Iranians to tweet in English, the lingua franca of the Internet — and not only in order to expose their government’s behavior to the world.

It is really hard to believe that a famous communicator like Malcolm Gladwell wouldn’t understand instinctively what it means to people simply to be heard. That goes double for people who are suffering in a just cause. It is strengthening to speak and be heard, and most strengthening of all to hear words of support in return, even (and maybe in this case, especially) from very far away.

Which brings us to another glaring difference between pre- and post-Internet revolutionary movements: the decreased ability of would-be despots to do their cracking down anything like as efficiently as they did before. Before one had heard the slightest word from official circles or news organizations of any kind, on Sunday night in the U.S., there were tweets out of Egypt from the protesters themselves claiming that two of the “looters” caught in Alexandria were found to have had state police identification on them. The same story kept right on emerging, too, from that point forward, from ordinary Egyptians who managed to get their views onto Twitter, all explaining how Mubarak’s forces had gone into state-owned factories and offered payment to anybody who would get on a bus to Tahrir Square and crack some heads for them. This is evidently a practice already familiar to Egyptians from other times of unrest, like the recent sham elections there.

Three nights later, on Wednesday night, I heard the same things reported on Warren Olney’s To the Point radio program.

This is why it has become necessary for today’s despot to shut the Internet down entirely and get rid of all the journalists, if possible, a feat which is becoming progressively more and more difficult, as recent events in Cairo have shown. In times past, men like Mubarak would have been able to crank up a spin machine pretty effectively in three days, a machine which could cook up a counter-narrative claiming that their “supporters” were the real thing and not bought-and-paid-for operatives, and then blow that narrative all over CNN and the BBC and the rest of the world press — if they were paying much attention at all. Just think how much easier to succeed in hoodwinking not just the foreign press but their own citizenry, too, in the complete absence of any readily available information to the contrary. We in the U.S. wouldn’t have heard a thing from any of the protesters themselves beforehand.

As matters stand, Omar Suleiman, the first Vice-President ever appointed by Mubarak in three decades, stands to inherit what amounts to the throne, so it would seem to benefit him to cool it, appear to be sane and moderate while still taking no steps to make the army protect the protesters. It could be argued that having to turn the Internet back on is worth a lot of Egyptian lives right now. Suleiman is the chief military spook, as Paul Amar, a UCSB professor, explained in a densely informative and worthwhile blog post yesterday.

The Vice President, Omar Soleiman, named on 29 January, was formerly the head of the Intelligence Services (al-mukhabarat). This is also a branch of the military (and not of the police). Intelligence is in charge of externally oriented secret operations, detentions and interrogations (and, thus, torture and renditions of non-Egyptians). Although since Soleiman’s mukhabarat did not detain and torture as many Egyptian dissidents in the domestic context, they are less hated than the mubahith. The Intelligence Services (mukhabarat) are in a particularly decisive position as a “swing vote.” As I understand it, the Intelligence Services loathed Gamal Mubarak and the “crony capitalist” faction, but are obsessed with stability and have long, intimate relationships with the CIA and the American military. The rise of the military, and within it, the Intelligence Services, explains why all of Gamal Mubarak’s business cronies were thrown out of the cabinet on Friday 28 January, and why Soleiman was made interim VP (and functions in fact as Acting President).

Amar explains that the different branches of the military and police have different historical affiliations and loyalties, the military is split, with some factions somewhat closer to the Mubarak regime than others. The outcome of revolutions is almost invariably dependent on which faction the army supports; one of history’s oldest lessons, unpleasant as it is to have to recall that here. Robert Springborg gave a gloomy assessment in Foreign Policy.

The threat to the military’s control of the Egyptian political system is passing. Millions of demonstrators in the street have not broken the chain of command over which President Mubarak presides. Paradoxically the popular uprising has even ensured that the presidential succession will not only be engineered by the military, but that an officer will succeed Mubarak. The only possible civilian candidate, Gamal Mubarak, has been chased into exile, thereby clearing the path for the new vice president, Gen. Omar Suleiman. The military high command, which under no circumstances would submit to rule by civilians rooted in a representative system, can now breathe much more easily than a few days ago. It can neutralize any further political pressure from below by organizing Hosni Mubarak’s exile, but that may well be unnecessary.

This is not a universally held view, though, which brings us to a final word on the potential value of Twitter and the Internet in general to the Egyptian revolutionaries’ cause. There is, to take one example, still the matter of over a billion dollars in American aid to think about. Because the protesters are taking their case not to governments or the press but to their fellow citizens of the world, there is hope that we can pressure our own governments to advance their aims.

This is a huge change in how global politics is beginning to be conducted and might be conducted in the future, if the world’s citizens are prepared to move in a concerted way on information provided. If the Egyptian protesters are tweeting and broadcasting photos and video to the U.S., proving that the Mubarak regime is killing them in Tahrir Square, isn’t it fair to argue that the Obama administration will become more reluctant to continue sending that regime our money? Because if many, many Americans are seeing such proof, it can, at the very least, reverberate in our next elections as well.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo: The Macho of the Dork and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.