Christian Aid Worker Danny Pye Has Been Held in a Haitian Prison Since October

by Abe Sauer

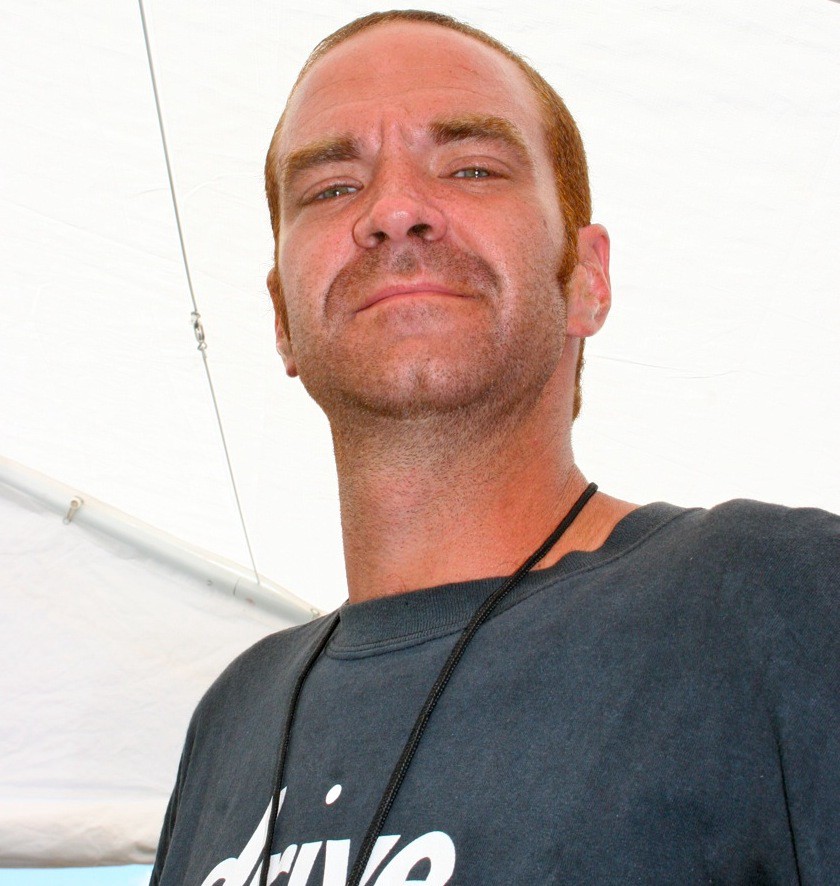

“I am amazed that I could spend four months in prison with no charge and the embassy does nothing,” said Danny Pye. “It’s just weird.” But so far, Pye is lucky. He’s only had malaria, several bouts of gastroenteritis and some kind of fungal infection — but not cholera. Many of the other 20-odd men that share his small room have not been as lucky.

Pye, an American, has been in prison in Jacmel since Oct. 13, 2010. He has not been charged with any crime. The only people who seem to know this are a few friends in Haiti, the country’s Ministry of Justice, newly elected Haitian senator (and former Jacmel mayor) Edo Zenny, the judge that refuses to sign his release, the NGOs with which he’s been affiliated, his wife, Leann, the 22 Haitian children whose only home is the orphanage that he and his wife built — and the U.S. Embassy.

A friend of Pye’s was able to get a cell phone into the Jacmel prison a couple days ago and he spoke with The Awl for the first time.

Thanks to cholera, the prison is quite literally a toilet. The only new structure at the prison is a building that’s been painted green and white, the color combo reserved in Haiti for medical buildings. This overcrowded prison within a prison houses inmates suffering from cholera, TB and HIV.

Reinforced last July after the earthquake, a Red Cross engineer said that Jacmel’s prison was vastly improved by the addition of bunk beds because “each bed has three levels and is big enough for at least six people to sleep in.”

Pye’s wife Leann says the Red Cross’ already-horrible description of the prison “makes it sound much better than it actually is.”

Pye’s cell, which he estimates is 10 by 12 feet, houses 25 prisoners. (That’s fewer than previously, when people were getting cholera.)

By car, Jacmel (Jakmèl) is four hours south of Port-au-Prince, on the south seaside of the island’s long peninsula. The city itself is home to 40,000 or so and the surrounding area another 100,000. With beaches and architecture built in the wonderful style of New Orleans by wealthy 19th-century merchants, Jacmel is not the desperate urban picture of Port’s Cité Soleil, the only Haiti most Americans know exists.

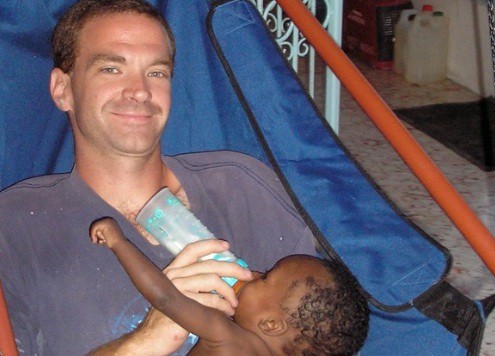

Pye is not one of the aid workers who flooded into the nation after 2010’s earthquake. In 2003, Danny Pye and his wife Leanne moved to Haiti to start an orphanage. They established the Joy in Hope Ministries in 2008, which now operates 16 schools that teach over 3,000 children. Danny and his wife themselves operate an orphanage, today home to more than 20 children: Mackendy, Evens, Berline, Blanca, Omega, Loudrige, Rico, Chachoue, Lovelie, Toto, Ticarlis, Magdaline, Elinda, Woody, Mackenson, Diane, Nerry, Nesley, Vania, Patrick, Tina, Slendia, Riann.

Last year, Danny and Leann separated from the ministry they founded to go their own way. After some negotiations and conflict, Pye and a representative of the organization appeared before a local magistrate on October 13th, to negotiate the legal dividing of property and other assets. Pye, to everyone’s surprise, was ordered to prison.

No charge was leveled by the judge against Pye. He was only told that he would not be released until he signed over his old assets — which he did, on October 16th. His family was then told he was being held in the court’s custody, pending an investigation. Haitian law allows judges to imprison a person for up to 90 days without charge while awaiting an investigation.

Danny’s wife immediately contacted the embassy.

Ryan Price, a longtime resident of Haiti and missionary with the Fellowship of Christian Optometrists who took the phone in to Pye, said that, recently, “they have been redoing the sewers under the prison, so the whole block smells like sewage.” Price said that Danny does get outside for some time every day; he used some of that time to carry water to other prisoners. Recently, “he is too weak to do this.” Being out in the yard can be dangerous, as fights are a regular occurrence. Fights aren’t the real danger, Price said: it’s the guards who storm the yard intent on breaking it up. They swing batons at anything that isn’t already lying flat on its face.

“Physically, I’m feeling better. I’m back to holding down food and liquid,” said Pye. That wasn’t the case two weeks ago, when Pye began not sleeping at all and retching after meals. The “food” he holds down is crackers.

There are about 200 people on his small floor. Pye said that a third of them are here for trumped up charges, or no charges at all. “When I first got here I thought it was closer to 50 percent,” Pye said. “But then you get to know people a little and… well….” He knows at least one cellmate who has been held for years with trial. “On Christmas Eve, a 14-year-old kid was brought in for stealing a goat worth maybe 12 dollars. He still hasn’t seen a judge,” he said.

It was also on Christmas Eve that Pye was released — for the first time. But, as he was walking out to meet his pregnant wife, Pye was spun around and returned to his cell. He didn’t even make it to the car: the same judge had issued a new charge, this time for possessing illegal documents.

It’s not been confirmed that those “documents” (Pye’s government-issued identification card) are “illegal.” It was the judge himself who did not understand the very laws he was there to enforce.

* * *

A reliable and trustworthy justice system can be considered the most important building block of a functional democracy. Lisa Quirion, a former Deputy Warden at the Correctional Service of Canada who worked with the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (which goes by the acronym MINUSTAH), said (before the earthquake), “People want to build hospitals, they want to build schools, they want to put a well in the town, but nobody wants to invest in prisons.”

It’s not just unsexy to invest in prisons, but in the whole justice system in general. Still, in the 1990s, USAID provided around $27 million to fund the Administration of Justice Program in Haiti which brought in American legal experts to improved magistrate, prosecutorial and judicial management training as well as expanding citizen access to justice services.

Today, a new joint program between the UNDP and MINUSTAH to improve “ethics, judicial competences, the application of just laws, public persecution, individual liberties in the judicial process, and economic and financial infractions” plans to involve “roughly one hundred” prosecutors… “by December 2011.” A spokesman for the UNDP said that the entire 2011 budget for training in the field of justice in Haiti is $500,000. (That’s a 100 percent increase over the 2010 budget of $250,000 for training in Haiti’s justice system.)

* * *

On February 18th, the head of Haiti’s justice system came to visit Pye, and told him that the judge had admitted the false documents charges were fraudulent. The judge, however, wants to revisit a contempt of court charge. Pye was told that he will be out next week. “It’s kind of the running joke of the place,” Pye said. “Each week it’s, ‘Oh, you’ll be out next week.’”

“I haven’t packed a bag,” he said.

Pye’s release would mean he might not miss the birth of his son. Leann remained in Haiti for much of February, to care for the orphanage. While seven months pregnant, she would ride on a scooter taxi to get supplies. She is back in Florida, where she and Danny own a small home, and her delivery date is imminent.

With Leann gone, the children from the orphanage bring Pye what meals they can.

As forgiving and good-spirited as Pye is (his positive disposition and good humor over the phone were remarkable), he is exasperated with the U.S. Embassy inaction. “I’ve never heard of a situation in which an American was held for four months without charge and the embassy did nothing,” he said. Medicines and other necessities have been supplied by friends or family. “I’m more disappointed than anything else,” he said.

Leann said that the embassy has, at best, given the situation a perfunctory treatment. Danny said that the few times embassy officials visited, their conversations were short and unproductive. Leann said they just told her to go hire a Haitian lawyer, which she did.

In November, Leann sought assistance from her U.S. Senator, George LeMieux. The response was an email with a PDF attachment telling her that the senator, due to privacy rules, would not follow up until Leann could “print, complete and return it to our office via fax.” In Haiti, faxing anything was impossible. Leann tried to get the paperwork together — and then this January, LeMieux was replaced by Marco Rubio.

Leann repeatedly followed up with the embassy. The embassy said it could not take diplomatic action, seemingly saying that it had no influence in the nation beyond what existed in the most formal of diplomatic rules. Just a year earlier, in a cable published by Wikileaks, the Embassy spoke of how a “key to our success and that of Haiti” was the embassy “managing” President Preval. How effective can the State Department be in influencing Haitian politics and reconstruction if it can’t even move the wheels for one American in prison?

* * *

There’s a deeper irony, because when the diplomatic community needed Danny Pye, he was there.

Seventy percent of structures in Jacmel were damaged or destroyed after the quake. With the aid focus on Port-au-Prince, few supplies reached beyond the city. What aid could get in had no on-the-ground organization. Creole speakers, Pye and Leann were able to quickly organize and reopen the airport. The two, with a team of Haitians, staffed and ran the Jacmel airport until the Canadian military arrived. Experienced in the area, and trusted by the community, the Pyes were invaluable in the international aid effort for which the diplomatic and NGO community took, and continues to take, so much credit.

And just a couple years ago, the US Embassy asked the Pyes to serve as wardens for the Sud-est (one of Haiti’s ten regional départements in which Jacmel is located).

Two weeks ago, Leann received an email from Brandon Doyle, the embassy’s vice consul. Doyle wrote that the embassy had “learned that, unfortunately, no action has been taken on his case.” Doyle went on to acknowledge that “this can now be considered a serious violation of Haitian law since your husband has been detained without charges for a period longer than allowable according to the laws of Haiti.” Doyle said that the embassy would prepare a formal diplomatic note addressed to the Haitian Ministry of Justice “calling for action on Mr. Pye’s case.” Doyle wrote this action is “the most formal and forceful course of action available to us and allowable under diplomatic practice” and that the note would be “sent early next week.”

That email, of February 8th — a Wednesday — ,meant that, after months, the embassy would not be taking any action until nearly a week later.

If the embassy’s limp official reaction to Pye’s situation is deplorable (and it is), its public reaction is inexcusable. Why, to this day, has the embassy not issued a public statement about Danny Pye?

The vice consul is certainly correct describing the “note” to the Ministry of Justice as the only course allowed it “under diplomatic practice.” But this says nothing about the use of the press, easily as powerful a diplomatic tool as a formal note. Within a day of the arrest of an American accused of shooting citizens in Pakistan, embassy officials were publicly calling for his release. The State Department has loudly, and continually, issued statements calling for the release of the American hikers arrested in Iran (who are now on trial). State Department officials have even issued a demand for the release from Syrian prison of a young blogger… who isn’t an American. When Khairy Ramadan Aly, an Egyptian carpenter employed by the embassy in Cairo, was killed just two weeks ago, the State Department issued statement of condolences from Secretary Clinton.

The embassy in Port-au-Prince as well issues press releases all the time. But not for Pye, even as he rotted away in a U.S.-funded hellhole, kept from doing a job that U.S. governmental bodies are proving themselves increasingly incapable of performing.

We spoke with a few journalists, one for a major US national source, all of who said they had never heard of the Pye case. Asked if they would have pursued the story had the the embassy in Port-au-Prince issued a statement about it, all confirmed that it absolutely would be newsworthy.

The embassy has not responded to numerous calls and emails made by The Awl.

Pye is a missionary but he’s of an entirely different stripe from the ministries with logos printed on every bit of aid they hand out. Pye went to Haiti to do with his bare hands what billions of dollars of American aid was failing to do. Pye, a U.S. taxpayer, remains in a MINUSTAH-run U.S.-subsidized prison.

But then this is Haiti, a place few can find a reason to care about. Unless, of course, 300,000 die… or Sarah Palin visits.

Residents of Florida, the Pye’s representatives are:

Senator Bill Nelson

Ph: (202) 224–5274

Email

Facebook

Rep. Vern Buchanan

Ph: (202) 225–5015

Email

Facebook

Senator Marco Rubio

Ph: 202–224–3041

Email

Facebook

An especially good target for pressure is Republican Senator Marco Rubio. As a member of the Christ Fellowship Church in West Kendall and a favorite of the Christian Coalition, one would think Rubio would be especially interested in (and in an especially good position to take advantage of the benefits of) seeing to the speedy release of one of the more (genuinely) faithful and pious of his constituents.

Never contacted a member of Congress? Email makes it easy, fast and free of cooties. For example, a message might go:

Dear Sir,

I was shocked to learn that Danny Pye, a Christian missionary, has been held in a prison in Jacmel, Haiti, for more than four months without charge. I was even more shocked to learn that the U.S. Embassy is aware he is there, admits he is innocent and yet claims it is helpless to do anything.

Danny Pye, a resident of Florida, desperately needs your help.

Here is the final kick to the stomach.

Through it all, Pye tells us his greatest fear, a sentiment echoed by his wife, is that this will somehow jeopardize their family’s opportunity to stay in Haiti and continue to operate the orphanage and school. “I plan on supporting them for years to come,” Pye said, just before handing the phone back.

Abe Sauer can be reached at abesauer at gmail dot com.