The Highly-Authentic Ghost of Townes Van Zandt

by Bethlehem Shoals

The twelfth highest-grossing film in America this past week was Country Strong. In it, Goop plays Kelly Canter, a boozed-out, decrepit country star just looking for another chance. Tim McGraw tackles the role of James Canter, the long-suffering cardigan that also happens to be her husband, manager and occasional tormentor. Leighton Meester is Chiles Stanton, a sweet young thing making the leap from pageants to the music biz. Garrett Hedlund is Beau Hutton, a dreamy rehab janitor who lives to play the honky-tonks. It’s the second film from Shana Feste — not a stage name — and Tobey Maguire snagged a production credit.

I saw it recently, on the smallest, dingiest screen at Seattle’s nicest multiplex, with the most vocal audience I’ve been a part of in my four years here. Country Strong isn’t the camp-fest my wife had hoped for, nor is it the cut-rate Oscar bait it sometimes imagines itself to be. It’s Crazy Heart, if Jeff Bridges had only been looking for an excuse to sing on camera; Nashville, if the caricatures were smugly two-dimensional; The Rose, with sheer volume replaced by churlish intimacy. Take a melodrama, drain it of all good, hackneyed sense, and shoot it simply, in natural light, and what’s left? Here the reader who has yet to see the film, and intends to, might stop reading.

Beau and Chiles fall in love, but only after she stops sleeping with James Canter, and only with the blessings of Kelly, who had been sleeping with Beau. While not in love with Beau, Kelly believed they had some spiritual bond based largely on soulful staring. Everyone is in love with each other, and it’s causing problems, and yet somehow, one of Gwyneth’s last pearls of wisdom is that we should all “fall in love with everything.” That line was big on Twitter.

Another part of this approachable clusterfuck is Chiles revealing herself to be more than a painted brat who will stop at nothing to conquer the charts. It has something to do with her writing a decent chorus; mostly, we go along with it because Beau says so, and he’s the source of all that’s credible in the film. Later, we find out that Chiles is white trash and ashamed of it, which is an important step. But in the epilogue, we see her for the first time without her make-up, and according to Roger Ebert, she’s more beautiful than ever.

By this point, Kelly has offed herself after a triumphant comeback show in Dallas, leaving a note about how happy she is. Country Strong, indeed. I’m not sure, though, it was all that different from the ending of Black Swan?

A gut-yanker that’s neither good nor heroically bad, Country Strong is absolutely inconsequential, if not hollow. And yet a week later, I find myself still thinking about it, just because of one stray exchange about mordant, depressive singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt. After two shows, McGraw’s character attempts to explain to Chiles that her and Beau’s are already stars to be reckoned with.

James (McGraw): The Austin Statesman’s saying that you’re the next Carrie Underwood, and he’s the next Townes Van Zandt.

Chiles (Meester): Who’s Townes Van Zandt?

James: He’s a singer-songwriter.

Chiles: Was he famous?

James: In some circles. But not as famous as Carrie Underwood.

There’s really no reason for Townes Van Zandt to show up in this movie, especially if it’s out to establish its country cred. But there he is. And with that, the balance of authenticity is thrown all out of wack, never to recover. Suddenly, remembering who you are and where you came from — the honesty that every good country fable seeks to attain — is supplanted by the wishy-washy possibility of finding yourself.

The patently absurd contrast between Carrie Underwood and Townes Van Zandt is a bit like being offered your choice of white wine or Percodan with dinner. Say what you will about the Piedmont brogue Colin Farrell affected for his character in Crazy Heart; at least that movie got the binary right. Van Zandt isn’t “real” in the way Johnny Cash or Merle Haggard are — he’s not even country per se, and he has as much in common with Dylan, Lightnin’ Hopkins or Fred Neil as Willie or Waylon.

But once the comparison’s made, Hedlund started to sound to me like a schmaltzy, diluted Townes — sensitive instead of wounded, in a way that makes his songs suited to either a first kiss or a break-up. (What’s the difference, anyway?)

Hedlund defines Meester, and fittingly, when we see the “real” her, she looks more like a liberal arts undergrad than the poor, scrappy girl from Tennessee. This makes zero sense, since growing up poor and Southern has always been the bedrock of authenticity in country music. Yet somehow, that side of Meester is incidental to her voyage of self-discovery. She may bond with Kelly over this shared experience, but in the end, there are things more universal and meaningful than roots. It’s like she has dropped out, not broken free.

Kelly, too, may have her humble beginnings to thank for her ambition, her insecurity and her pluck, but even she falls under the spell of the Hedlund/Van Zandt orbit. Or, rather, the film lurches at the chance to make her into that kind of character. Country Strong opens with the two of them hangin’ out in her room at the rehab center, strummin’ her beat-up guitar and seeing who can most adeptly compose a song out of thin air. I get that the well-loved acoustic is a Willie Nelson reference (half the guitars in the movie look like that), and there’s a certain campfire quality to the scene. At the same time, though, it also recalls the communal Nashville “guitar pulls” where Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and Mickey Newbury, among others, would swap songs and extend their ideas. There are no publishing rights in this place.

Chiles and Beau also use songwriting as a proxy for courtship, foreplay and eternal bond, and plan to run away together to the coast where they will make music for themselves. At the film’s end, we are again a long way from pop production. But it’s Kelly Canter — poet, drunkard, a Romantic too fragile for this world — who only makes sense if the film throws in Townes Van Zandt. Otherwise, she risks being too, well, country. And certainly too strong for the ending to make any sense whatsoever.

Like the romantic entanglements in Country Strong, which nimbly manage to avoid the slightest trace of homoeroticism, these different forms of “real” deftly step all over each other without any sense of tension. It’s a decidedly awkward movie about a world that can rarely be bothered with that mood.

External to the film, and my reading of it, is yet another matter of cred. Feste has told numerous outlets that Kelly’s character was inspired by Britney Spears and Michael Jackson; this reduces her story to tabloid formula, using country music as a different costume, and more lurid disguise, for the overly-familiar. Yet at the same time, there’s this telling take from the LA Times, rebroadcast on the soundtrack’s official blog:

Paltrow’s latest role as a faded country singer is a gamble for an actress known more for art-house fare. But her upcoming CMA awards spot and other high-profile moves are a step in the right direction for building credibility.

That presents a question, of course, of whether playing the CMA’s — becoming, for one night, a real fake country musician — amounts to any kind of authenticity, or just cunning simulation that plays well on YouTube.

Country Strong was about the perils of fame long before it concerned itself, however unwittingly, with the fine lines of its setting. At the same time, at the register of marketing and fan reception, Gwyneth had to prove herself worthy of the role. Given the way the film turned out, I would have much rather seen an actual country diva play against type and tear herself apart, like a rhinestone-studded Dancer in the Dark. There’s no law that only the ladies of “art-house fare” can access deep feelings. And if the real challenge here wasn’t negotiating the terrain of country music, but making sure the costumes fit right, hell, Country Strong probably would have done a better job of fooling the audience without making Paltrow do all that heavy lifting.

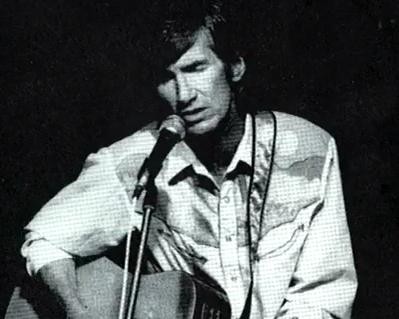

Then again, even for Townes Van Zandt there were limits to authenticity. One of my favorites — and quite possibly his bleakest — is “Highway Kind,” which to my knowledge, appears on 1972’s “High, Low, and In Between,” and then one, maybe two, late-career live albums. This has always baffled me. For reasons that will take too long to explain, Townes protege Steve Earle was in the room when I made my first promotional appearance as an author. He had just finished a long-overdue record of Van Zandt covers, which he had decided would emphasize his idol’s less doomy side. Earle felt like Townes’s legacy had become remarkably one-sided; there was much more there than suicidal contemplation.

After we talked about baseball for a minute, I sensed an opening to asked a question that had bugged me for years: why did Van Zandt play “Highway Kind” so infrequently? “Well,” Earle said, “there are some places so dark that even he didn’t want to visit them again”. He made it sound like, even for Townes Van Zandt, music was imagination, escapism.

Then again, Townes trained a parrot to pilfer cough syrup and had a pet monkey that doubled as his bodyguard in the wilderness. Kelly Canter has a pet baby bird named “Loretta” that she nurses back to health at the rehab center. Presumably, something awful happens to Loretta when Kelly brings her to a biker bar and goes on a bender. But Country Strong tactfully drops the subject. What kind of sick movie kills baby birds, even off-camera?

Bethlehem Shoals is a founding member of FreeDarko.com. Pay attention to his book and FD’s art emporium.