Taste Has Never Met Shame: I Love You, Conor Oberst!

by Ben Dolnick

Seven or eight years ago, when I wasn’t yet old enough to feel embarrassed about it, I saw Conor Oberst play at a bar downtown. Before he went onstage — a stage that was really just a foot-high platform with a stool — he sat drinking in a booth with some friends. Having been drinking myself, I made my way to his table, where I stood as if I were a waiter, and, realizing too late that I ought never to have come over at all, I sputtered some combination of the words love and music and so much. He gave me a much friendlier look than I deserved, signed a scrap of paper for me, and turned away, mortified on my account.

My shame that night was of a particular, botched-encounter variety, but in the years since, the feeling has broadened into something more general, until it’s become one of the main emotions I associate with his music. Sometimes I think there ought to be a coat of arms for all of us who listen to Oberst’s band Bright Eyes past the age of twenty-six. WITH LOVE AND SHAME, the motto would read. The handwriting would be the cramped and tortured scribble of a high school freshman.

At various points in the past few years — when, at more recent of his concerts, I’ve felt, amidst the mascara-streaked faces, like a childless man lingering at the edge of a playground — I’ve imagined that my love for Conor Oberst was finally preparing to die a respectable death. But lately, as I’ve been waiting for his new album, checking Amazon a couple of times a day to see if, by some freak accident, it’s slipped into the world early, I’ve given up. Years from now, when I’m wandering through life bald and L.L. Bean-jacketed, I’ll probably still be listening to him tremulously describing his beloved high school girlfriend combing her hair, and I’ll probably still be both ashamed and covered with goosebumps. But why the shame? And, come to think of it, why the goosebumps?

The long version of an explanation for my love would include defensive references to Elliott Smith and Bob Dylan, as well as an anxious discussion of his surprising way with lyrics, his disarming voice, his shockingly steady output (ten-plus albums, beginning when he was fifteen) and a dozen other things.

The shorter and more honest version, though, would amount to not much more than: play “Light Pollution” starting at about 2:10 and listen for at least thirty seconds. Does that part at 2:26 when his voice kind of lifts off from the line he’d been singing, as if some booster-rocket of emotion had deployed, do anything for you? If so, I’ll see you at Radio City in March.

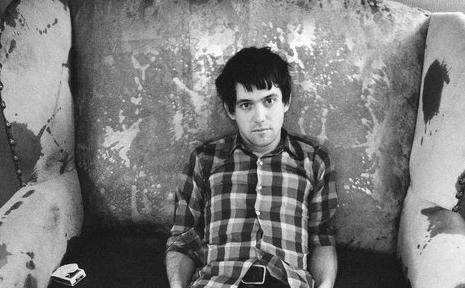

If not — or if what it does for you is akin to what a bite of Thai food does for someone with the cilantro-hating gene — then no amount of argumentation is going to convince you. Not for you is my insistence that his last few albums are actually considerably less mawkish than his early ones, or that his satisfyingly screamy side-project Desaparecidos is worth a listen. Oberst is one of those musicians that some people hate in a visceral, biological way. From his first albums, in which he sounds like someone’s clinically depressed little brother who’s gotten hold of an answering machine, to “Lua,” that weirdly successful single from a couple of years ago in which he sings “I know that it is freezing” in a voice so fragile that it sounds as if he may himself freeze like a baby bird left out in the snow, these people find him not just bad but laughable and somehow offensive. Do his eyes really need to look quite so wide and unguarded in almost every photograph? Couldn’t he at least brush his hair out of his face?

And the thing is, I don’t need to look outside myself for a person who feels this way. The eye-rolls are coming from inside the house. This is the peculiar burden and shame of the no-longer-young Bright Eyes lover: within him is a Bright Eyes hater, only he can’t be heard over the shouts of “I love you, Conor!” coming from upstairs. I know very well that to admit to loving Bright Eyes is to admit to having an overgrown brain region devoted to self-pity, sentimentality, regret and a handful of other not very appealing emotional states.

And yet: there’s no musician I love more. “A Line Allows Progress…” is the kind of song that Macaulay Culkin might sing if The Good Son were ever turned into a Broadway musical, but that part at 1:05 when his voice wobbles on “stumble ‘round the neighborhood…” has been, on dozens of cold afternoons when I’m running errands ‘round the neighborhood, more dear to me than my winter coat. “First Day of My Life” is, in its way, as syrupy as any Michael Bublé serenade, but it happens to be a syrup perfectly engineered to flood my emotional circuit-board.

This stubbornness of taste is one of the things, as I approach thirty, that I’m learning to accept. Our senses of taste couldn’t care less about our carefully plotted visions for ourselves. I would love to love Saul Bellow, but by page fifty of Herzog, something within me has wandered into another room. Taste doesn’t work for reason; reason is a skinny underpaid clerk in the office of taste. Taste occasionally dumps a heap of papers on reason’s desk and says: Here! I like Face/Off but hate both Nicholas Cage and John Travolta! Explain that! And so reason stays late constructing tenuous arguments, while taste goes home to watch “King of Queens.”

But here, anyway, is one of the arguments my reason has come up with while my taste has been counting down the days until “The People’s Key”: we ought to be grateful to Conor Oberst for daring to be so embarrassing.

It must feel bizarre, at almost thirty-one, looking out from the stage each night and seeing this ocean of loving adolescent faces. He must be tempted to make an album that wouldn’t occasion such goo, something cold and brainy or something soulless and slick, anyway something that wouldn’t have so much of his own feeling in it. But year after year, album after album, he puts his undisguised, quavering self on public display.

And that takes a weird kind of bravery, in a culture like ours. Look at the Huffington Post or TMZ or Gawker. Look at the percentage of stories that are about people getting SMACKED DOWN or BUSTED or HUMILIATED IN A LIVE INTERVIEW, or else are about people falling on their faces (sometimes literally) or being photographed at inopportune moments. Think how bad it feels, being laughed at. Feel how tempting it must be, as a musician, to pull your head back into your shell and record an album of electronic trance music that Pitchfork would give a 9.4.

But enough with reason.

Nabokov, in one of his many smart and crabby lectures, said that the only important organ for evaluating an artist is the stretch of flesh between the shoulder-blades. “That little shiver,” he said, “is quite certainly the highest form of emotion that humanity has attained.”

Well, going solely by the flesh between my shoulder-blades, Conor Oberst has been the most important artist of my adult life. More important than Alice Munro, more important than Philip Roth, more important than the Beatles, the Coen brothers, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Updike, Joyce, Nabokov himself — these giants, these heads on Mount Rushmore, these warranters of two-full-page-obituaries, have each caused me fewer moments of neck-hair-raising bliss than a sulky, elfin, musically undistinguished guitar-playing kid from Omaha. My frontal lobe may as well get used to it.

Ben Dolnick lives in New York. His new novel, You Know Who You Are, comes out in March.