Larry Polansky Is Making Hardcore Beats

by Seth Colter Walls

Last week, while on a walk to visit some Seattle fishmongers, I spent a few minutes watching an elderly Indian man playing sitar at the corner of an intersection. Any pair of lay ears could perceive the old musician was talented, and so he had an appreciative crowd, despite this being a fairly cold sort of January morning. I remarked to a friend that no one was likely confused or intimidated by the genre definition of the music he was playing. Even though it was happening on the street, it was clearly a formal music: not meant for dancing or soundtracking a TV show or casually accompanying any other type of entertainment. Listeners were meant to sit still (or stand), watch, and simply listen to the music on its own terms. And yeah, its form came from India. Thus: Indian Classical Music. Simple enough. No one freaked out or seemed insecure. We all enjoyed it.

Like most countries with sufficient access to leisure, America has its classical music, but we’re so confused about whether we ought to resent or admire the broader world (esp. Europe) regarding matters of class and taste that we often have trouble perceiving it with anything like confidence.

Is it in a concert hall? And are the performers wearing fancy clothes? If not, it must not be a symphony! And since the worst-slash-most-embarrassing thing you can do about “high culture” is to be “wrong” somehow, a lot of people just give up trying and scrap the whole project.

(Sidebar! This, by the way, is one of the more familiar refrains I hear from people who lament their own high intake of celebutante/reality TV-material and who also have some nervous ambition about switching up their culture diet: the notion that the barrier of access to anything more “high minded” is littered with ego-decimating landmines that they, the TV-watchers, will trip over due to their ignorance, making such a bloody spectacle of themselves in the process that it would have clearly been better to “stay in the zone” with which they were previously familiar, even if they were becoming increasingly bored by its confines in the first place. I am convinced this public misconception is nearly 100% a product of various popular culture tropes about how behaving the “wrong” way at a “classical” concert will earn you a metric ton of icy stares from better-dressed jerks, such that the the reality-TV viewer would have been better off staying home and remaining satisfied with consuming the TMZ Evening News. Being myself someone who behaves inelegantly at regular intervals, I can only say that I have not found this to be the case in actual American cultural life, away from the TV. Anyway.)

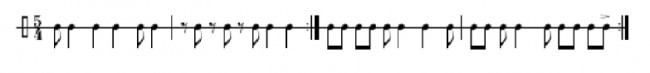

To illustrate how non-normative/non-European — or really, how street-corner ready — our country’s independently wonderful formal music can be, I am going to show the entire notated score for a genius piece of contemporary American classical composition. You do not need to be overly familiar with musical notation to get its radical point. Are you ready? Here we go:

This is “Ensembles of Note,” by Larry Polansky, who is also a professor at Dartmouth. But instead of this being some kind of stuffy, Ivy League-affected jam, quite a bit of his piece here is left up to its performers to determine. (No, this is not a cop-out; please keep reading.) Truly, though, the first thing to know is: Oh, Sister, does this piece ever knock. The final 90-second section of the version on New World Records, from the all-Polansky-composed album “The World’s Longest Melody,” constitutes my favorite hardcore jam going back a long time. (Trust me, at least to start with, that the piece builds over the course of its 7-plus minutes to merit that punkish assessment.) It’s also just great noise music, in some parts.

[wpaudio url=”http://3-e-3.com/01%20Ensembles%20Of%20Note.mp3″ text=”Ensembles of Note, by Larry Polansky.” dl=”0″]

[Performed by ZWERM (electric guitar quartet), [sic] (saxophone quartet + drums), and Stefan Prins (live electronics). Copyright 2010, New World Records. From The World’s Longest Melody. Used with permission.]

Here you could just stop reading my blah blah and listen to the piece, because it presents itself just fine on its own. But in case you’d like something to read while listening, what follows is a brief primer on how the composition works. In the spirit of post-John Cage American chance-music funstyle (apologies, Liz Phair), the number and diversity of instruments are left up to the performers. Merely one instrument has to keep the above score strictly in mind at all times. That written part is an eight-measure ostinato (or, “repeated thingy”) in which two different two-measure patterns are each repeated once before moving on to the following one.

Listen to first few seconds of the mp3 posted above, and look at the score. You can probably just hear the beats and make sense of the notes written down on the page. [First two measures = “ONETWO THREE FOUR FIVESIX / … ONE … TWO … THREEFOUR FIVE.” Then these two measures repeat again, before moving on to the second 2-measure pattern which repeats as well, before starting over at the very beginning, etc.]

Even if you can’t follow every measure independently (as the piece progresses, it becomes slightly fun/tricky), you’ll get how that 5/4 time signature gives the piece a mutant kind of swing, no matter which of the two patterns is being played — and how the whole deal also provides plenty of opportunities to bang hard. (For a very clear and more pop-oriented display of what happens in 5/4, try the opening verse of PJ Harvey’s “Hook.”)

Now for the other instruments. Every time the twice-played, two-measure patterns loop back to their beginning, the instruments not bound by the score are meant to fill in the notes of what will become a simple melody. Every time the loop is repeated, the other non-ostinato instruments add one progressive little bit of the whole puzzle. The performers either improvise this melody as they go along, or have some kind of fixed melodic idea settled on ahead of time. (The performers on this version sound like they’ve drilled down at least a few ideas.)

You know how Diddy told a producer that on Last Train to Paris “I want a beat that makes me feel like a white man in a basement in Atlanta”? That’s an abstract musical direction right at the level of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s infamous “Aus den sieben Tagen” (in which performers are told to “Play a vibration in the rhythm of the universe”). Polansky’s allowance for musician-directed chance is at once more composed and more radical than some of this “intuitive” method stuff that’s become common practice on both sides of the pop-classical divide for a while now.

Several of the musicians on this recording have worked closely with Polansky in the past, and have a pretty good idea of what he’s up to. “I trusted them musically so much on ‘Ensembles of Note’ that that particular piece didn’t need my input,” Polansky told me over email. “I gave them a few comments on earlier performances, recordings, etc., but not much. They’re great musicians. Their ideas surprised me and I loved them.” Still, in the written instructions to his one-page score, Polansky does offer the following advice: “Take your time. Stop adding notes when it becomes too difficult to remember your melody.”

And so, over the course of a few minutes, we have bass and electric guitars and saxophones and electronics whirring/beeping up a number of figures we can anticipate each time the repeated rhythm thingy runs through its sequence. Polansky closes the note attached to his piece with the following instructions: “At some point, after each of the melodies have grown to around 8–16 notes, on a signal from someone in the ensemble, performers drop out or move to the ostinato, which may be played a few times in unison before the piece ends.”

This is the hardcore part, and it comes at the 6’20” mark in the above recording. This is when it really goes hard in the paint — and with greater insistence than anything Lex Luger conceived last year. This is when it grinds better than anything on the last Kylesa record. (Note: I adored “Flockaveli” and “Spiral Shadow.” I’m just saying people who like that music might give this a try also!)

This ending — I’m so wild for it. If someday the New York Philharmonic were to program this as an overture (70+ musicians, can you imagine?), I would do all sorts of inelegant things that might earn me stares from better-dressed jerks — but then also maybe no one would care, since the entire musical culture would have changed.

That’s not particularly likely to happen, though. When I emailed Polansky to ask about his career and the prospects of higher-profile performances, he very gently made fun of the question.

“Commissions?” he wrote. “Pretty funny! But seriously, I just work as hard as I can, think about the most interesting things as I can, spend no time or energy on self-promotion or ‘career,’ and try to move forward, take musical risks, follow my interests, and on the side, to support others to do the same. I’m happy when the music is performed, but happier when it’s understood, happiest when I’m working on something new.”

Still, the experiential upside of new music that’s this deep underground is that it becomes impossible for anyone to make fun of how you approach it. As much as it’s up to the musicians, it’s up to you as well. Are you tired of everything being beamed to you fresh from its heavily molested time inside the funhouse mirror of the endlessly refracted metaculture? Here’s a 7-minute portal that can slip you light years away from its influence.

BAM BAM BAM BAM BAM BAM BAM.

Seth Colter Walls finally got himself on Tumblr the other week.