Two Hours in Marinette: Lessons From a School Shooting

by Abe Sauer

Samuel Hengel put a .22-caliber Ruger, a Hi-Point 9mm Luger, two knives and 205 rounds of ammunition in a duffel bag. Then, on Monday morning, he walked out of his Porterfield, Wisconsin home for the last time — another young American boy going to school with guns, ammunition and intention.

The November 29 school shooting incident in northern Wisconsin, at time of publication America’s latest, is being spun as a success of the post-Columbine system. A trained school staff and law enforcement levelheadedly defused a heavily armed student prepared to do the worst. But when police finally responded to the 911 call, more than two hours had passed since gunshots were fired. These gunshots were heard by many — although, apparently, not the on-duty police officer stationed at the school.

The Awl interviewed friends of Hengel, numerous students that were present and law enforcement officers that responded and facilitated the school’s “active shooter program.” We found that Hengel likely knew, in advance, that he would not survive the day. We also identified an eminently fixable and substantial oversight that may exist in many other schools’ “active shooter training” programs.

At 1:40 p.m., Samuel Hengel said he was sick. He asked to be dismissed from Valerie Burd’s sixth period social studies class to use the restroom. Minutes later, Hengel returned to the classroom with his guns and ammunition. Hengel stood before his class and fired three shots, one of which abruptly ended a showing of a film on Hercules.

Then nothing happened, and that’s a problem.

A junior who was upstairs in a math class told me, “Yeah, I heard a really loud bang. Didn’t think anything of it. Well, I heard three, but one was really loud.”

These three shots were heard by both students and teachers in adjacent classrooms, but dismissed as random noise.

Amy Hansen, the Marinette Police School Liaison Officer, who had been a one-minute walk away the whole time, and whose office is directly wired to the several cameras stationed in the hallways around Burd’s room, got into her car, drove back to the police station, and began to file her daily report. When I asked Marinette’s police chief if Hansen heard anything, he told me, “Of course not.”

At 2 p.m., Samuel Hengel, Valerie Burd and all 26 students in the classroom were shocked and confused. The room still smelled a bit of discharged gunpowder. The gunshots had been so loud. How could nobody have heard that? Burd’s classroom is in an area of the school called “the barn,” a major thoroughfare. Burd’s classroom is adjacent to four others where classes are being held. That puts dozens of students and faculty within maybe 50 feet of repeated gunfire.

But nobody came to Valerie Burd’s room. At 2:15, the bell rang, ending sixth period. At 2:20, Burd’s seventh period students knocked on the door. Valerie Burd cracked the door open and sends them to go to the library. Burd put a note on the door, similarly instructing other seventh period students. If Burd had a reason for making no mention of a gun, or why she declined to appeal for help, she has not yet revealed it publicly.

The Associated Press report begins this way: “Sam Hengel was by all accounts the least likely of 15-year-olds to bring two pistols, knives and more than 200 rounds of ammunition into his social studies class.” What’s more, he had loving parents. He had good grades. He had friends. But according to the definitive “Safe School Initiative” report (PDF) by the Secret Service and Dept. of Education, that compares 37 school shootings, Hengel was pretty much exactly a likely candidate.

Like most attackers, Hengel had “no history of violence and came from solid, two-parent homes.” He was a boy, was doing well in school at the time of the attack, appeared to socialize with mainstream students or was considered a mainstream student himself, was involved in organized social activities in or outside school and had never been in trouble or rarely been in trouble at school — all typical characteristics of school shooters.

Hengel, like nearly two-thirds of all attackers, had a known history of weapons use. That Hengel’s parents would have no idea of their son’s plan sadly fits the paradigm; an adult or parent had information about their boy’s plan in only two cases. So where do the parents fit in? The report states, “Over two-thirds of the attackers acquired the gun (or guns) used in their attacks from their own home or that of a relative.”

Finally, the report states, “Most attackers showed no marked change in academic performance friendship patterns, interest in school, or school disciplinary problems prior to their attack,” a characteristic that is perfectly in evidence with Hengel’s dumbfounded friends, family and teachers, who all note that the 4.0 student never seemed depressed or troubled at all.

In the days after the attack, all manner of rumors circulated, all of them vague, almost all of them secondhand. A few told me that Sam broke up with a girlfriend or that Sam was having trouble with a teacher. As many as mentioned bullying mentioned “he was not bullied.” Keith Schroeder, Hengel’s former Scout leader was cryptic, saying to the press, “I know there was some problems at school.” But he did not elaborate. Nobody will elaborate, and Sam Hengel cannot.

The “Safe School Initiative” study also found that over 80 percent of shooters both plan and reveal the intentions of their attacks in advance. So far, Hengel has seemed an anomaly in this respect. School administrators, the district attorney and the police have all made it a point in statements to repeatedly warn that we “may never know why.”

However, it appears he alluded to his plans with one friend. The Awl was shown text messages Samuel Hengel exchanged shortly before the shooting that indicate it was likely he had planned his attack and did not expect to live.

It didn’t seem that odd to Frank — who asked that his real name not be used — when Sam asked him about the book Columbine. Sam knew Frank was reading the book a year ago, and they had discussed it then a little. The book, by Dave Cullen, debunks many of the myths about the infamous shooting. A few years older than Sam, Frank now lives in another state, which is probably why the police have not yet spoken with him. He told me it wasn’t unusual for him to hear from Sam at random times, a text here or a Skype or IM session there. The subject was often the Packers. Frank said, “Pretty much every time the Packers won he was happy for the week.” This time though, Sam was interested in how the Columbine shooting had changed police tactics.

Sam asked Frank about the two shooters and which had been the leader; which had left all the letters; which didn’t really want to do it. “He also talked about how both Harris and Klebold’s autopsy were on the internet and he thought it was weird that info was readily available to people,” says Frank. Frank just figured Sam was asking “because he was interested in the law enforcement field.” Frank said that conversation took place just before Thanksgiving.

Asked about how his book featured in this event, author Dave Cullen told me, “Unfortunately, Columbine took on iconic status, and when most people think of school shootings, it comes to mind — for all of us, including the next perps. If Sam Hengel read that part of the story, I wonder what he made of the Columbine killers’ real end,” says Cullen. “I don’t know how much truth or mythology about the past affects a kid desperate enough to pick up a gun. They are all emotion at that point, no reason.”

Cullen added, “The trouble is that we in the media jumped to conclusions on Columbine and got most of it wrong. So kids considering an attack don’t understand what that tragedy was about, and the myths sound much more appealing than the truth. The reality is that Eric and Dylan wanted to blow up the school, kill hundreds and go out in a blaze of glory. They were miserable failures, and died in quiet squalor.”

* * *

The bell at 3:12 p.m. ended seventh period and the school day. Students poured into the halls, zigzagging to lockers. Some went to practice. Some went home. Hengel had to expect somebody to come by the room, to force his hand.

But nobody came to Valerie Burd’s room. Nobody. One junior told me that he walked by Burd’s room “every time I go to my locker.” On this day, he didn’t see a thing. Nobody did. School was over for the day, except for 26 students and a teacher in room A111.

We know Sam Hengel likely did not intend to leave the school alive. Days after asking Frank about Columbine, Sam texted Frank about Green Bay’s heartbreaking last-minute loss to Atlanta. It was a day before the shooting. Frank asked Sam about who the Pack played the next week. Sam texted: “49ers at Lambo but dude I cant watch it. u will have to watch it for me.”

Frank told me, “When he said that, I thought he meant that he couldn’t watch it in person. But looking back on it, I believe he meant that he couldn’t watch it on TV either and that’s why I was supposed to watch it for him.”

* * *

The 911 call transcript reads, “Yes, this is Corry Lambie from Marinette High School. We have a student holding an entire class hostage right now… I’m leaving to go up to the commons right now… tell them to hurry.” It is 3:48 p.m., two hours since shots were fired.

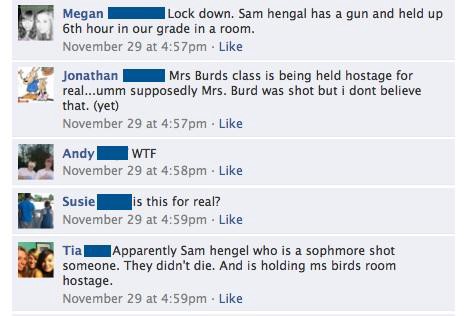

Within minutes of the principal’s call, the school is evacuated. Minutes after that the first texts and Facebook updates go out. Val Burd is rumored to have been shot.

The police and emergency vehicles that flooded the school grounds may have put students in mind of the “Every 15 Minutes” program held just three weeks earlier. The drunk driving safety event included a mock car wreck, police cruisers, rescue personnel. Chilling only in retrospect, the exercise included a costumed Grim Reaper who entered classrooms every quarter hour to “kill” a student. The “dead” students spent the night at a local hotel to create a feeling of loss. The next day, assembled students listened to parents speak of their “dead” child.

During the standoff, Sam Hengel was exhausted. Ms. Burd spoke with the police on his behalf but he had no demands. They couldn’t give him what he wanted because nobody knew what he wanted. He looked at the class: Tyler, Brad, Zach, Paige, Kayla, Marisa, another Paige, Hayley, Alex, Alysha, Nathan, Austin and the others. He decided to let five students use the bathroom, surely knowing they wouldn’t come back. This was 7:40 p.m. He knew the SWAT team from Green Bay is crouching outside the door.

A few students talked about what happened. Nathan Miller told the local Fox affiliate, “They were yelling at him to get on the ground, and they were yelling at us to get out and everything was kind of a blur at the moment.” Others choose to remain silent. One 16-year-old student who was in the room turned down an interview request with a simple “Fuck. You.”

At 8:03 p.m., Sam Hangel fired three more bullets into a computer. Fearing the worst, SWAT breached the room, and Sam put the gun to his head.

“That’s not the first thing that you think of in a school. School’s the place where you’re supposed to feel safe,” said a junior, who was in an nearby English classroom when Hengel discharged the gun. She said the shots sounded like “a door upstairs being slammed or a table being dropped.”

A freshman who was in the sixth period World Geography class immediately next to Burd’s room tells me that several students jumped at the gunshots during sixth period. One boy even joked that everyone should “get down.”

“We only thought that there was people slamming doors up stairs. If you would have made us make a list of what we thought it was, that wouldn’t be anywhere near the top of my list,” he said. The freshman says his teacher dismissed the shots as a door slamming.

Another student emailed to say, “there were two bangs durin 6th hour but we just thought it was somethin normal.” On Facebook, several Marinette students posted on others’ walls about “those sounds we heard.”

A junior who hunts and also heard the shots explained, “In the woods it’s open where you hear the echo more than the actual thing. I don’t know. I think just at first it didn’t seem real to be a gunshot in school.”

In the days after the shooting, the school’s top administrator bragged to the press that recently the school’s “educators were all involved in a mock shooter situation.” That claim is a little misleading as the teachers really did not play any part in the “shooter” part of the exercise.

Through an open records request, The Awl obtained a copy of the “Marinette Co. School Shooting Exercise Plan” carried out on Aug. 27, 2009. The “Scenario Summary” of the report on the training exercise states:

Time: 0830 hrs Marinette High School is preparing for the new school year and all High School staff and school administrative personnel are on campus for in-service meetings and classroom preparation. At approx 0830 hrs masked gunmen storm the campus firing rifles and small arms. Several people are shot in the area of the main entrance to the High School. The gunmen start firing at anyone they encounter and begin searching the building for victims.

The report describes an impressive and extensive plan to handle and coordinate the school and emergency services after an active school shooter had been identified.

Marinette County Emergency Management Director Eric Burmeister told me that the place Hengel chose, room A111, was noteworthy as this “A-area” was the same place police and emergency services had staged its mock shooter exercise. Burmeister explained that the training used “simulation” — gunfire simulating technology. “It’s probably not as loud as live rounds but it’s close,” he said.

So just 15 months before Sam Hengel fired three real gunshots in this corridor of classrooms, a team of police had used ammunition that produced sounds comparable to real gunshots.

But given safety concerns, only a few school administrators were present for this segment of the training. The teachers who participated did so in a separate part of the exercise and were not present to hear what gunfire might sound like in their everyday environment.

It’s an absence that raises a simple question: Would adding a program that familiarized staff (and maybe students) with the sound of gunfire within their everyday environments add a valuable, and cost-effective, dynamic to the security preparedness of schools?

Sam Hengel’s funeral was held on Sunday, Dec. 5, at 1:00 p.m., and at the same time, the Packers were beating the 49ers, a game they would go on to win.

Note: As residents of a small community, nearly all students and parents interviewed asked to do so anonymously. Only Frank’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Abe Sauer is working on a book about North Dakota. You can reach him at abesauer [AT] gmail.com.