Mannahatta, Mon Amour

Before the “events” of 2011, which if you were “lucky” made your life surreal and possibly oneiric (and if you’re reading this, I’m sure you know what I mean), I had lived in a part of Manhattan (specifically: the northern or “unsettled” part) for close to two decades. Sections of this neighborhood nevertheless remained unfamiliar or “foreign” to me, although I had heard rumors about a specific “location” said to be found somewhere west of Broadway — i.e., close to the river — and most likely north of the bridge (but this fact was far from certain), a place known for its mutating and unmappable streets, represented on the internet by gray “zones” or numbered grids. I heard related stories about children and the elderly and real-estate developers leaving home and never returning; about unused subway tunnels built by prior administrations underneath the bedrock and encrusted in diamonds (now worthless); about vast swaths of virgin or “old-growth” forest stretching down to the banks of the Mauritius (as we now call it) populated by indigenous beings who predated human settlement; and finally about censored doctorate dissertations written by manic depressives who (after predicting this very future in which we now find ourselves) had without exception hurled themselves from the steel arches to their watery graves.

When I first encountered these stories or rumors or fables, it was during a period not only of youthful skepticism, but also when, owing to other “obligations” (as we used to refer to them), I had lacked the time (or really, the inclination) to look for this mysterious landscape, and so it remained undiscovered and possibly fictive, at least as far as I was concerned. In the spring of 2011, however, not long after the fighting stopped, and as soon as it was warm enough, I went outside (i.e., I left the “shelter”) with a plan to be more systematic. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to find this place, or what exactly I intended to find there, but even the possibility of its existence seemed to offer a kind of relief or possibly condolence during what we all understand were difficult conditions, to say the least.

I began at what remained of 155th Street and each day walked from one side of the island to the other. (It’s not as far as you might think.) I went back and forth, observing what remained of the city, most of which was deserted except for the stone towers and the corpses, which like those littering the mountains of Tibet were (owing to the “methods utilized”) “frozen” or paralyzed in a posture of death or “departure.” I was not deterred; by now we’ve all seen enough of these soulless bodies to be largely impervious to the instinctive terror such sights presumably would have provoked in all but the most callous of us a few years ago; then, too, the facial expressions of these victims or “casualties” (to use the official terminology) were uniformly serene, which I understand is cold comfort, but like most during this “emergency phase” I took what solace I could find.

Already the vines were beginning to stretch down from what I presumed to be the long-uninhabited regions to the north, wrapping their tendrils around the carcasses of rusting vehicles and the frames of broken doorways and widows. Soon, I thought, these streets will resemble those of Coba. Although I sometimes heard (or possibly imagined) the rustling of leaves and the crack of branches (noises quickly supplanted, at least in my ears, by the pounding of my heart) I saw no sign of animal life.

I continued to work my way north, deeper into the woods, where I passed a large house filled with broken glass and unlit rooms. I remembered hearing it described (in whispers) by two men I had observed years earlier while feigning sleep on the A-train. Fear hovered over this structure like a miasma, and as I edged past, I peered in to the rooms and observed the vaguely horrifying and decaying detritus of lives abandoned in a second and forgotten for an eternity.

The air became heavy and wet; it wasn’t so much stagnant as undisturbed. I had never felt more alone but was no longer afraid, and perhaps even transfixed by the dazzling effect of the coruscating light filtering through the canopy. The path narrowed and led me through an arch; here I detected (or imagined) a susurrus wave of disembodied voices, speaking in a language I couldn’t begin to understand. To them, I suspected, our lost cities were nothing more than anthills.

A stone lion greeted me with blinded, doleful eyes.

His twin brother had been decapitated.

I carefully walked up the steps, which were buried in leaves.

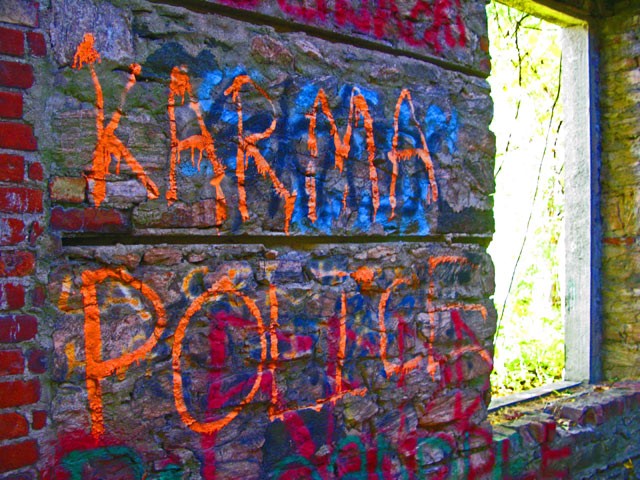

I arrived at the ruins of what appeared to be a small mansion or perhaps a guardhouse that had apparently been inhabited by the “Karma Police.” (I suppressed a shudder.)

There was no roof but the foundation seemed solid. I entered and stood in the middle of the room. I resisted the temptation to remember anything from my past, knowing that here, for once, it was irrelevant.

The sempiternal buzz of the eldritch voices reached a fever pitch. I looked out the window into a clearing, where I had had a foreboding sense of being judged. I was both a spectator and a participant in the assembling tribunal; civilization had vanished, and only the pillars remained.

Matthew Gallaway lives in Washington Heights and is the author of The Metropolis Case — which is available now! Perhaps you read its glowing, stunning review in the Times this week?