Captain Beefheart, Gilbert Arenas And The Fate Of The Weirdo

by Bethlehem Shoals

Captain Beefheart died with the mark of the weirdo on him. If the twelve-tone Howlin’ Wolf acolyte who dabbled in Surrealism and late Coltrane hadn’t once been mistaken for a rock musician, his passing wouldn’t be national news. But he was, and thus became the kind of eccentric who can’t simply be ignored. Beefheart had to be confronted.

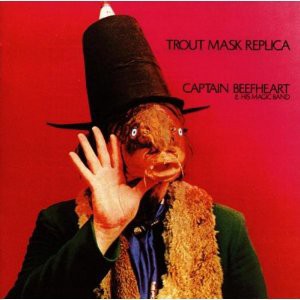

Some records don’t get reviews, they get epigrams. Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica isn’t “the sound of a generation”, “when [insert genre] grew up”, or “the greatest no one ever heard.” Instead, it’s “that one you have to listen to at least once” — after which, presumably, you’re either converted for life or come away hopelessly alienated and yet somehow better off for it. That was certainly my experience with it. It was recommended to me as a rite of passage, and although I was already listening to Albert Ayler and early Sonic Youth for fun, my first encounter with the record was jarring. Trout Mask wasn’t just noisy or ecstatic — it was ugly and proud. And yet this 90-minute song cycle could never be mistaken for nihilistic. It was creative in the most literal sense, a loud, harrowing language that had burnt away or scrambled once-familiar vestiges.

At the time of these sessions, Beefheart’s Magic Band was a bleary-eyed, zonked-out cult of blues primitivism, free jazz, and contemporary composition that sprang out of the best and worse impulses of the sixties. With virtually no money, they lived like ascetics in a rented California house and devoted themselves to music that had no business aspiring to naturalism. Their leader was imperious, even cruel — former band members claim that Beefheart denied them food and sleep, and egged on conflicts that sometimes led to violence — but also strangely earnest. The contorted, off-kilter riffs he drilled them on were his version of school spirit, if not divine messaging. There was also a satirical impulse there, something Beefheart shared in common with on-and-off buddy (and frequent biographical reference point) Frank Zappa. Yet Trout Mask is so thick with both bile and gleeful nonsense that it’s hard to separate irony from garbled prophecy. What does it all mean? Demanding in the most literal sense, this record turns the hard questions back on the listener.

Many serious Beefheart fans prefer 1970’s Lick My Decals Off, where Magic Band acknowledges the outside world just enough to treat the music as advanced, if still alien. While it’s an idiom all its own, it’s one that can influence others, not just spawn imitators. In its own haphazard way, Lick My Decals participates in history, alluding to the punk, art rock, and fusion that would follow. But it’s Trout Mask that represents Beefheart’s great crossover moment, his most abrasive work and his most relevant. In the 41 years since its release, has come to signify utter, impregnable strangeness, and Beefheart, a Great American Original who, for all we know, may have at some point been considered for inclusion in a Gap or Microsoft campaign. Trout Mask is the bum posted up in front of a fancy restaurant like he knows something about the menu.

The day after Don Van Vliet died, Washington Wizards guard Gilbert Arenas was traded to the Orlando Magic, giving him yet another chance at a comeback. From 2002–2007, Arenas was a voluble scoring machine who put the long-suffering Wizards back in the playoffs. Arenas also had a theatrical streak, a sense of himself as performer and sports as entertainment, that only heightened his competitive nature. And then, as a sidehow, there was “Gilbertology”, the unusual, colorful, and just plain goofy behavior that made him an internet sensation.

In the nineties, Dennis Rodman’s dyed hair, piercings, and tabloid-ready personal life (I dated Madonna! I’m bi!) passed for “weird” among basketball players. By contrast, Arenas’s shtick was too unpredictable to wear thin. When Arenas was described as “weird”, it was part of a game — his game — that engaged fans in a way athletes just didn’t anymore. He put a personal touch on every buzzer-beater or scoring rampage. Every locker room appearance could yield a classic line; every magazine feature, some new revelation about what made him tick. Lang Whitaker deemed him “the first blog superstar”; between his perilously confessive blog on, of all places, NBA.com, and seeming inability to give brief, topical quotes for reporters on deadlines, Arenas needed the web as much as it needed him. David Roth wondered if Gil wasn’t “a throwback to the charismatic, recognizably human hoops superstars of the ’70s and ‘80s.” Chuck Klosterman concluded that “People are not fascinated by Arenas because his behavior is outrageous; they’re bewitched because they have no idea what his behavior is supposed to signify.”

Arenas was a confounding presence in the league but, as long as he was playing well, was also an altogether welcome one. That changed when he missed the better part of two seasons with knee injuries. No one wanted to acknowledge that the possibility that Gilbert Arenas might actually be, well, weird, in the way Ron Artest had proven himself to be. Artest was a problem; Arenas was a brand with rough edges. When Arenas’s luck changed, Gilbertology took on a darker tone, and yet for those two years, somehow waiting on Gil’s return to action was part and parcel with letting him have a personality. He came back healthy, and seemingly engaged, for the 2009–10 season, only to sent his career — and the Wizards organization — into a free-fall that January. As a particularly acrid joke, Arenas decided to settle an argument with teammate Javaris Crittendon by putting four weapons in Crittendon’s locker with a note to “pick one”. One was a gold-plated semiautomatic Desert Eagle. That shit is diesel.

What happened next remains murky, but it’s worth noting that the disagreement was over cards; that Arenas had already, reportedly, idly threatened to blow up his teammate’s car; and that DC has zero tolerance gun laws. He was allowed to keep playing, pending investigation by the league and law enforcement. Yet Gil simply couldn’t help himself. Within days, he was dancing around in pre-game warm-ups with his fingers cocked back like six-shooters, picking off invisible enemies and smiling where a smirk would have been more appropriate. His teammates, even strait-laced Antawn Jamison, surround him, laughing. Commissioner David Stern was not amused; he promptly yanked Arenas from active duty, eventually suspending him for the rest of the season.

To say that the initial incident, or the FINGER GUNZ dance, were worth the trouble is foolish. Arenas threw the Wizards into disarray — luckily, they won the draft lottery and nabbed Kentucky phenom John Wall first overall that summer — and, as he has acknowledged this year, threw away his last best chance at being a featured star. What’s often forgotten, though, is that you can’t rationally separate Gil the Sinner from Gil, Comic Genius. Last winter’s meltdown was the price of his earlier, more convivial weirdness. And yet somehow, in going beyond the pale, or suggesting a psychology that went deeper than “weird”, Arenas lost the mark of the weirdo. He returned to DC a rueful, frank character; when he spoke to the press, it was somewhere between a suicide note and the grizzled drop-out who could’ve been a contender. In Orlando, no one’s expecting the return of Gilbertology as part of the package. If anything, he’ll be graded on his professionalism, regardless of how well he plays. Anything else augurs danger.

Critique and dissent are, in theory, part of our socio-political mainstream. Rebellion is a commodity; deviance, however principled, repulses. What attracts us, though, is this construct of the Weirdo. This crystallized, kooky individualism, the notion that originality is both profound and entertaining, is also distinctly American. We care about Beefheart, and once cared about Arenas, because what made them interesting transcends what it is they actually did well. Weirdness also spills over boundaries of race, class, and gender; it makes for beloved, if ultimately harmless, figures. But it’s a delicate balance. Arenas went too far; it was by accident that Beefheart was brought into orbit and judged as one of our own. That the professional athlete ended up marginal, and the resolute avant-gardist an unlikely outpost of pop, attests to just how little control the Weirdo has over his own fate.

Bethlehem Shoals is a founding member of FreeDarko.com and a regular contributor to NBA FanHouse. Pay attention to his book and FD’s art emporium.