Understanding Kanye: Sweet, Sweet Robot Fantasy, Baby

by Mike Barthel

If you want to put your finger on why Americans have this nebulous but persistent sense that the way we live our lives is in some deep way wrong, I would point you toward the unresolved conflict between our ethos of individualism and the fact that worldly achievement is now almost impossible without being what’s known in the dialect as a “team member.” While we can still chant “USA #1” with perfect assurance, it all seems unreal without a life-size statue of a superstar. Which is why so many are fascinated with Kanye West. Kanye’s career is the story of one man joining and then transcending the organization, becoming the ghost in the shell: not in the system, but of it. But even this mechanized perfection does not necessarily bring happiness, and that is the message lurking in the cybernetic heart at the center of “My Dark Twisted Fantasy.”

The story of Kanye’s career is the story of his search to become a cyborg and then deal with the consequences of that transformation. In the early days, he was all too human, working at the mall and sleeping on a couch in an overheated Chicago apartment. When he finally got his foot in the door, it wasn’t as an individual artist but as a company man, becoming a house producer for Roc-A-Fella. This is the old-fashioned modern American path to success: work hard, get noticed by someone in power and then get promoted to a place of prominence within a larger organization. But Kanye wanted something more. He wanted to achieve on his own, to break free of the system. And he would slowly realize that the only way to do so is to become more than human.

Kanye had to fight to be taken seriously as a rapper, and he only succeeded once he started becoming a cyborg. A car accident in 2002 left him with a metal plate in his jaw, and instead of trying to cover up the unreal, he brought it to the fore, recording a song while and about how his jaw was still wired shut. The resulting single, “Through the Wire,” was his first hit, and the song that convinced Roc-A-Fella to give him an album deal. He had found beauty in a piece of machinery that would normally be hidden under a more believable imitation of the real. In so doing, he created a verbal analog of his most famous production technique, “Chipmunking,” in which a sample is sped up to match a faster beat and consequently raised in pitch as well. Chipmunking is a kind of joke about beatmaking; producers work to make a sample match their preferred tempo without changing pitch, but by exaggerating these seams, Kanye made the unnatural pleasing. He was learning the value of the mechanical in and of itself.

This influence of the mechanical floats in and out of his first two albums, though it fights with his natural tendencies toward the natural. You can hear the tension on “Slow Jamz,” a prime chipmunking track, when Kanye contrasts the unnatural speed and pitch of Luther Vandross with the biological abilities of Twista, someone able to imitate the hyperspeed feel of digital sound manipulation with natural verbal techniques.

When the other guest on “Slow Jamz,” Jamie Foxx, pops up on the second album’s “Gold Digger,” it’s to do the same convincing imitation of Ray Charles that he did in the movies. But after Foxx’s intro, we get the real Ray Charles, or maybe the “real” Ray Charles, since it’s a recording of a live performance that’s been cut up and rearranged. Foxx’s intro is a sort of signal to us that there’s more going on here than just sampling, but once you’re into the track, it’s easy to lose those issues given how closely the use of Charles’ “I Got a Woman” hews to rap conventions for sample use.

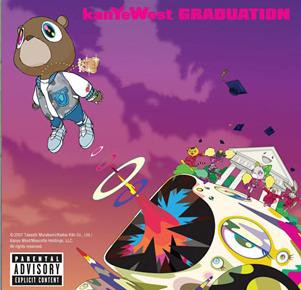

Where Kanye makes the big jump into the cybernetic, and where he consequently starts to become a real artist, is on Graduation. You can see it just in the progression of album covers.

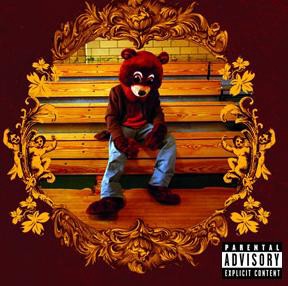

On “The College Dropout,” the mascot, “Dropout Bear,” is sitting on the bleachers in a tableaux that sticks closely to the real (realness being, after all, a key component of hip-hop, and this when Kanye was still trying to prove himself). It’s dusty, there are cracks in the floor and discolorations on the wall, and it’s clearly Kanye in the suit. It’s taken from a particular perspective, and you can see wrinkles in the clothing.

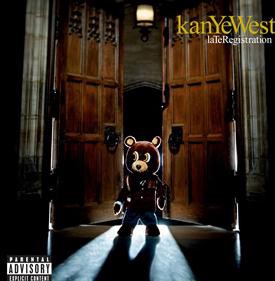

The cover of “Late Registration” is still a recognizably real image, but everything is heightened. Dropout Bear is shot from a distance and as a physical presence no longer has much roundness. Strong backlighting is employed to throw Bear’s shadow toward the viewer, and the character manifests itself as two connected two-dimensional shapes that could almost be a three-dimensional shape split down the middle. There’s no longer necessarily a human presence in the suit, and instead of looking like a repurposed mascot costume, the outfit is now clearly custom-created, given its side-glancing eyes.

On “Graduation,” however, any pretense to realness is gone. Dropout Bear, as depicted by Takashi Murakami, is now no longer three-dimensional or even two-dimensional, but superflat. The multiple visual points of the “Late Registration” cover have merged into one consistent plane, sending the message that past, present and future are irrelevant; all can combine if seen from the right perspective, or by the right set of eyes. The physical form of Dropout Bear is now not a real suit or a fake suit but merely a cartoon. But, of course, that’s what it was all along: the placement of pigments on paper (or pixels) in a particular form. That a real referent does or does not exist is irrelevant. We have moved beyond the anxiety of the artificial to a full-blown embrace of the unreal.

Kanye’s cybernetic identity came to the fore on “Graduation,” and nowhere more so than on lead single “Stronger.”

Aside from the fact that it was built around a sample from Daft Punk, a group who maintain the semi-ironic schtick of always appearing in public as robots (with remarkable consistency), the track’s video showed Kanye literally becoming a robot. Placed inside a machine operated by the Daft Punk bots, heart covered with gauze as if it had been removed, he becomes a cyborg in a sequence similar to the title sequence of Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 animated film Ghost in the Shell (he then goes crazy and wrecks shit in a brief homage to Akira). Unlike the Daft Punkers, cyborg-Kanye isn’t encased in metal, but is indistinguishable from a human; his time in the machine seems to have imbued him with a cybernetic sensibility without changing his appearance. When he lip-synchs, he appears only as a video image, filtered through electron scans or superimposed ghost-like on images of machinery. He submits to the machine and, in so doing, is able to become as powerful as a machine.

If the robot theme wasn’t as obvious throughout “Graduation” (though see also “Barry Bonds” and the mechanical manipulation of images in Spike Jonze’s video for “Flashing Lights”), it became unmistakable on “808s and Heartbreak.” But where “Graduation” depicted technology largely as aspirational and beneficent (that Akira nod seems out-of-pace with the general message of “Stronger”), on “808s” the mechanical, and particularly the digital, took a much darker turn. This was no accident. It seems almost unkind to point this out, but between “Late Registration” and “Graduation” Kanye’s mother died after complications from plastic surgery. Technology had always served Kanye well before — in the form of his producer’s tools, it was the vehicle that took him from obscurity to the cusp of stardom — but now his mother’s own cybernetic changes had ended in death. The mechanical had turned on him.

[More: Kanye was now a full-fledged cyborg.]

When he premiered his first track from the album, at the 2008 VMAs, the spot on his chest that was covered in bandages in the “Stronger” video was now filled. But instead of a real heart, he had a digital one, a pin made up of red LEDs blinking on and off, a crack running down the middle. The operation had been, at least on its own terms, a success. Kanye was now a full-fledged cyborg. On “Love Lockdown,” his voice was filtered through AutoTune with a sharp attack and a subtle bit of distortion to produce the sound of a human trapped, maybe unwillingly, inside a robot. The same effect was applied to almost all the vocals on the album, and while it was deliberately artificial, it was also, like he had said, stronger: where before he could only rap, now he could sing. The off-key caterwauling of “Drunk and Hot Girls” was now a precise tone full of a kind of electric soul. It wasn’t the raw emotion of humans, but the synthesis of emotional impulses and mechanical restraint, a computer’s inauthentic attempts at automatic expression which nevertheless sprung from a real human need to communicate.

Despite the sadness on “808s,” it still represented a kind of victory dance for Kanye. He was now a big enough pop star that he could release an album of robot R&B; and still maintain his position. He had risen through the ranks of the organization only to assert his power as an individual and continue to maintain that independence even as he became enmeshed in the machinery of popular culture. If he wanted to wear pastel or do an entire video as a tribute to Ralph Bakshi, he would. He had managed to have it all. Like the cyborg at the end of Ghost in the Machine, he was inhabiting the system to such a degree that he had risen above it. He could travel freely and act as he wished.

Following “808s,” it’s best to sum up Kanye’s two years by just mentioning that he was called a “jackass” by the current President of the United States and leave it at that. But that heel turn allowed him to work through his darker impulses in a way his audience could understand. “808s” came out of nowhere, more or less, and the audience responded largely with bafflement. His new album, though, is explicitly about being the bad guy. It’s a shame that so few people seemed to really get “808s,” but the fact that he’s able to pull off the evil thing now is a testament to the degree that his music is tied up with his public persona.

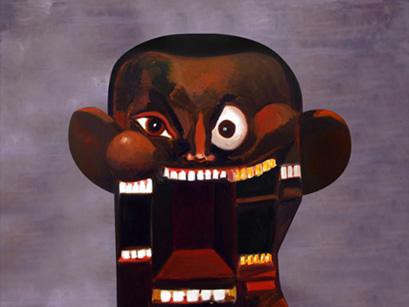

In any event, for the latest album? There are, by varying counts, four or five different covers, all by George Condo. Let’s just say the imagery has fractured.

As has been pointed out, the question about “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” is: what’s the fantasy about? Critic Nitsuh Abebe makes a good case that it’s about being royalty, and I like that, but in the context of Kanye’s career, the fantasy seems more like a recognition of the only out he has left. He can’t go back to being human; the heart has been removed — and has itself committed seppuku.

http://player.vimeo.com/video/14747182

He’s not going back to the bleachers on the cover of “The College Dropout”; he is, after all, a machine now. The downside to being a human-machine hybrid is that you’re subject to all the limitations of machinery while still being responsible for your actions in the way humans are. All that’s left for him now is to become fully machine, dropping the human agency to let himself become a feather blown by the winds of public sentiment, embracing the idea that he is whatever you say he is.

But, of course, he’s not. He’s much more than that. And this is the real fantasy: that the system isn’t a mass of complexities and ambiguities, that it is simple and easy, that heel turns are real. “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” is a nightmare of living in George W. Bush’s world, one where there are only absolutes and blacks and whites and things are simple. Kanye has ascended into the system only to find it is too complicated to communicate to us, practiced a radical simplicity only to discover that reducing himself to the simple on/off of binary code still allows for unimaginable shades of gray. On “Fantasy,” Kanye declares himself a monster, indulges in an extended nightmare of martyrdom on album centerpiece “All of the Lights,” and closes with an apocalyptic quote about America (which has been manipulated from its already fairly radical source to seemingly imply a coming civil war).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=afvMLRkLY6w

The video for “Stronger,” the lead single, features Kanye at the center of two warring sides, presiding over a battle between good and evil. And we love that shit. It’s a lot easier to understand than the ambiguities of “808s,” and as Kanye shows, we don’t even need to put ourselves in the place of good to like it. Being evil is fun, too.

The love for Kanye is because he represents our own sort of fantasy. In “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Donna Haraway (oh yes!) makes fun of technological utopianism that pretends we can break the chokehold of history by replacing flesh with machine. Kanye seems like the last free American, powerful enough to tear out his own heart and replace it with something more efficient, something stronger. He seems to represent a possible solution to our emptiness, a way of escaping the soul-crushing communitarian symbiosis of the organizational life. He’s beating the system by becoming one with the system.

But he sends the message loud and clear — and sometimes hourly — that this has its own cost, and imposes its own particular restraints. This we’re less down with. We want to think that our unhappiness comes from something besides ourselves, and so we identify the source of restraints and try to place the blame there instead. What restrains us now are the vast systems in which we’re all enmeshed, and so we turn to the fantasy of self-reliance and total independence. You can see this everywhere from the Tea Party to the environmentalist movement. Who wants to have to rely on other people or other countries or machines in order to live our lives? If we could just break free of our responsibilities to anyone other than ourselves, if we could just grow our own food and ride our own bike and be left alone by the government, then we could finally be happy.

Kanye gives the lie to this dark, beautiful fantasy. The only way to break free of the system is to give up your humanity, and even then, we are still subject to the system’s periodic spasms of condemnation. Being the only critic who ever got to George W. Bush wasn’t enough for America when Kanye decided to menace a white girl. The fantasy of becoming a robot is one in which you are shut off from the rest of the world, protected from it by technology. But the outside world will always intrude, particularly if you keep poking it with a stick. Kanye plays to our fantasies by holding out the possibility that our glum everyday experience — “the watered-down one, the one you know,” as the spoken intro to “Dark Fantasy” puts it — isn’t the only game in town. There’s something else out there, he says. But, of course, there’s not, or at least not yet. The only thing realer than real is what we make for ourselves; the only thing truer than true is the truth yet to come. Kanye is telling us that simplicity is a fantasy.

Mike Barthel has written about pop music for a bunch of places, mostly Idolator and Flagpole, and is currently doing so for the Portland Mercury and Color magazine. He continues to have a Tumblr and be a grad student in Seattle.