Harry Potter and the Incredibly Conservative Aristocratic Children's Club

The richly imaginative details of J.K. Rowling’s fictive world, it must be admitted, are pleasurable. The hot-rod brooms, the flowing robes and flying cars, the goth Heaven of the sullen Slytherins, the snake language and the magic wands enclosing phoenix feathers or unicorn hairs, the metamorphic potions, the leaping or fizzing sweets! All these have been fully and lovingly realized in the Warner Brothers movie adaptations of the Harry Potter books, including the most recent, which is a fine-looking but completely incoherent mess with a morally bankrupt and politically repugnant story at its core.

No expense has been spared, naturally; Warner Brothers has seen $5.7 billion out of these movies in theatrical revenue, so far. The visual imagination of director David Yates (he has helmed Harry Potter 5 through 8) is kind of pedestrian but there are some lovely set pieces, notably an animated vignette that is just so beautiful and interesting. The movie was bound to be entertaining, a spectacle, provided you don’t look too closely at what’s being said.

The multitude of sins committed in Rowling’s imaginative but horrible story can be roughly divided into three classes: ethical or pedagogical, literary and political.

Some years ago I was driving a carful of kids to some practice or party, and from the crowded back seat I heard one breathlessly ask the others, “When you were little,” (they were maybe twelve at the time), “did you think you were going to get a letter from Hogwarts?”

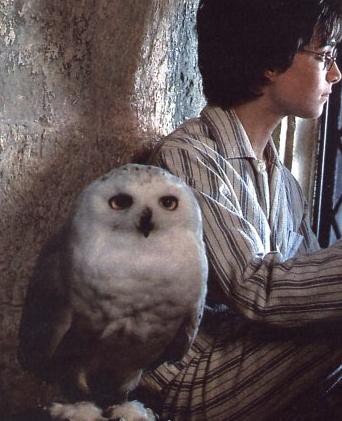

Giggles arose in the car, some lofty and some sounding a little embarrassed; a couple of the kids admitted that they had in fact fantasized about receiving such an invitation. (When you are chosen to attend Hogwarts, the public school for wizards attended by Harry Potter, an owl shows up with a letter informing you that you are one of the lucky ones.) This concept of “chosenness” has always put me off the Potter books because it seems so harmful for kids, even though I am a lifelong SF/fantasy fan (a genre where this crops up frequently, to be sure).

In the world of Harry Potter, rules are for the little people. The “wisest” adult, headmaster Albus Dumbledore, showers magical gifts and indulgences on his favorites and lets them break every rule because they are so special, better than all others. How come they are so much better? Well, the general awesomeness and favoriteness of Harry Potter and his friends is mostly arbitrary, the result of the chosenness itself, rather than of effort or application. Harry Potter is just naturally fantastic at flying around on a broom and conjuring illuminated stags up out of his soul and things, Hermione Granger is just naturally the most brilliant student Hogwarts has ever seen, and so on. Ron Weasley, the impoverished aristocrat, is a Sancho Panza-like figure whose rough common sense is meant to keep Harry on the straight and narrow; his noble blood is his “chosen” quality, and marks him, too, as an unimpeachable Establishment figure.

Which brings us to the disconnect between reality and appearances regarding the nonconformity that Rowling so hamfistedly praises at every turn. Harry Potter and his friends, far from being renegades, are in fact slavishly obedient to the all-powerful, omniscient, do-no-wrong Dumbledore. And why not, when he provides them in advance with every rare and fabulous magical gewgaw and hint they will ever need in order to extricate themselves from whatever peril they may find themselves in.

Rowling’s adherence to the old English principle of blood-nobility — that weird but deeply held superstition that has caused countless English protagonists to discover that unbeknownst to them, they were peers of the realm all along — is in stark contrast to the biggest conflict depicted in the Potter stories, the blood purity conflict. The bad guys, Voldemort and crew, are race purists, anti-Muggle (meaning anti-human), which is to say that they are against any magical Muggles or intermingling of Muggle blood (“Mudblood”) and wizard blood. Yet Rowling’s heroes are all noblemen, with the exception of one: Harry Potter learns in the old-fashioned surprise way that his father was a fabulously rich wizard, and his godfather is a rich aristocrat, too; Ron Weasley is a nobleman of the purest blood, though poor. The sole pure-Muggle wizard of any consequence at all in these books is Hermione, the author’s personal projection of herself (there are two other minor pure-Muggle wizards, boys, both of whom are bumped off). So this story can be read pretty effectively as an explanation of why J.K. Rowling should be allowed to hang around with the nobility (she is smart, is why).

Maybe, incidentally, the reason no other woman as smart as Hermione appears in the books is that J.K. Rowling, like the Turk, can bear no sister near the throne. Her volcanic ego burns down everything in its path. Where the Twilight books are works produced from and for a state of sexual yearning and frustration, Rowling’s “wizarding world” is a fantasy place created for the benefit of Hermione Granger, for her infinite sagacity, foresightedness and teacher’s-pet-hood to be rewarded at every turn.

In any case it is a horrible thing to be teaching children, that you have to be “chosen”; that the highest places in this world are gained by celestial fiat, rather than by working out how to get there yourself and then busting tail until you succeed. If the “special” and “chosen” and “gifted” automatically receive all the honors there are, then what would be the point of working hard to achieve anything? So it is really terrible to hear these twelve-year-old kids so smitten with the idea that fulfillment would literally fly to them out of the sky, via owl.

Rowling is a self-avowed liberal who gave a million pounds to the Labour Party in 2008, but her values are Tory through and through. In her books it is the hoary old white guys who run everything; women are popped in here and there for liberal flavor. The tokenism is unbelievable.

Rowling named her first child after Jessica Mitford, the lefty Mitford sister (as opposed to the Nazi-sympathizing ones). Rowling often says she read Mitford’s Hons and Rebels at age fourteen, and that it affected her profoundly; this book in fact provides a perfect illustration of Rowling’s political disconnect, because Jessica Mitford was the daughter of the second Baron Redesdale, a “terrific Hon,” as the Mitfords would have said. She was a super-blue-blood with rebelliously liberal views. It’s exactly this privileged, elitist compassion-from-on-high that Rowling admires and has consistently depicted in the Potter books. But the liberal values, the openmindedness, the diversity, are all fake.

I am no fan of Ann Althouse, but I had to admit to a shudder of recognition when I read her criticism of liberals last week:

What is liberal about this attitude toward other people? You wallow in self-love, and what is it you love yourself for? For wanting to shower benefits on people… that you have nothing but contempt for.

This may not be such a very good description of liberals in general but it is an excellent description of J.K. Rowling. In the “touching” climactic scene in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the house-elf Dobby has been “liberated” by, and now sacrifices himself to save, Harry Potter & co. The house-elves as depicted in the movies are horrifyingly pathetic, small, cringing, grateful; the sad, brave little creature Dobby literally expires with the name of Harry Potter on his lips. It’s like freedom is the gift of the chosen ones to bestow, and those thus benefited can die of gratitude and be “properly buried,” which really, there is this long burial scene complete with Harry Potter and shovel. It’s a perfect illustration of the “liberal condescension” that conservatives are always yodeling about, and it made my hair stand on end.

So don’t think about that! Think instead of the strapping young buck Rupert Grint, a fine young actor who manages to rise above the tawdry, maudlin script, or even more, of Helena Bonham-Carter as the queen of the goths, Bellatrix Lestrange, whose gorgeous performance had me totally rooting for the bad guys, as usual. She’s always got a magic wand or a knife at someone’s throat, that girl. Alan Rickman as Severus Snape, too, is as seductive as ever. Just to hear his voice for me is easily worth the price of a movie ticket; really he could read the phone book aloud, for all I care.

The most conservative element of Harry Potter’s world is that it is a materialist paradise, full of costly and rare magical artifacts, invisibility cloaks and piles of “wizard gold” at Gringott’s Bank. Things, that you can make toys out of, things that you can worship and desire and buy. There’s nothing in this story of alleged iconoclasts and rebels that would present the slightest challenge to the establishment. That’s why the story dovetails so easily into a series of Hollywood blockbusters.

The Rowling story of the Single Welfare Mom Who Made Good is not exactly accurate, either; her background is solidly middle class, her dad was a Rolls-Royce engineer, she read French and classics at Exeter, and the father of her first child (whom she divorced, rather than the other way around) was a Portuguese TV personality.

So this good liberal’s face is absolutely the face of the corpocracy. The number of lawsuits brought all over the world by Rowling and Warner Brothers against practically anybody who would dare to slap the Potter moniker on so much as a work of fanfic would curl your hair. Well, finally she allowed this one guy to write a fanfic novel, after having threatened to sue, perhaps because she knew she wouldn’t have won. If it were up to J.K. Rowling, I think Jean Rhys would have been thrown in jail for daring to write Wide Sargasso Sea. Which is fanfic, too, come to that.

In the best-known and most terrible of these lawsuits, the proud liberal Rowling saw fit to sue a fan who’d devoted years of his life to making an online encyclopedia about her books. I don’t believe I’ll ever cry again over the plight of an alleged copyright violator but you never know, I guess. Steve Vander Ark wept openly himself when he testified at the trial, and even though Rowling personally sued him, he later wrote on the blog part of the Harry Potter Lexicon — just like a house-elf! — that he was “still Jo’s man, through and through.” It just breaks your heart, the integrity and gentleness of this man, the love he bears these wretched books, the way he was so wrongly disgraced. A shorter version of Vander Ark’s book finally did see the light of day, in 2009.

On the literary side, suffice it to say that Rowling is ferociously dull and long-winded, that there is no suspense, that she kills people off (nobody Chosen, though) simply in order to show how serious things have become; magical artifacts are produced, used once for the specific purpose for which they were invented and then never seen again; the bad guys, whose actual aims are hopelessly opaque, have got the immemorial bad-guy cluelessness regarding the element of surprise, they let one opportunity after another to bump off our heroes slip past them, etc. Christopher Hitchens’s 2007 review in the New York Times is generous, but pretty searing, too. (“The repeated tactic of deus ex machina (without a deus) has a deplorable effect on both the plot and the dialogue. The need for Rowling to play catch-up with her many convolutions infects her characters as well.”)

Anybody should write whatever he or she pleases, of course, and there’s no doubt that Rowling did something right in creating her fictional world of Quidditch and faux-Latin magical incantations, if only because so many people love it so dearly. But if you have a young Harry Potter fan in your orbit, you might steer him or her toward Philip Pullman, whose Dark Materials trilogy is genuine in every way that Harry Potter is false; a fully realized work of fantasy to rival Tolkien in its wisdom, inventiveness and questioning. Because Pullman’s novels really do threaten the establishment view of religion and institutionalized coercion, because they are really subversive in the manner in which Harry Potter pretends to be, the Hollywood establishment chickened out completely and made a perfect hash of the first Pullman movie. Tom Stoppard, who’d adapted the original screenplay, was dumped by director Chris Weitz (of American Pie fame), who preferred to write his own. Hollywood is, unfortunately, an absolute tool of the corpocracy, and will never be equal to any story that presents a legitimate threat to conventionality or to materialist values.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo: The Macho of the Dork and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.