Why Harry Reid's Nevada Field Operation Is Losing

by Natasha Vargas-Cooper

If there’s anything that could save Harry Reid from getting ousted by Sharron Angle on Tuesday, it would be his campaign’s ability to run a competitive ground game: tight coordination of precinct canvassing, disciplined phone banking, targeted literature distribution, quality control over hundreds of volunteers and — above all — clean, up-to-date voter lists.

Based on what I saw yesterday at Democratic Party headquarters in Las Vegas, it’s not happening for Harry Reid.

Here is how Sharron Angle’s field campaign works. Their telephones link up to a Republican voter database. Once a phonebanker has made a contact, she punches a number on the keypad to report whether the person has voted already, how they intend to vote, whether it’s a wrong number or a hang-up. This updates the database in real time. After you disconnect, the phone autodials a new number.

In one hour at Angle HQ, I made 87 phone calls. If I talked to someone who already voted or who told me to “suck off” (true story!), I pressed a button and they were removed from the bank.

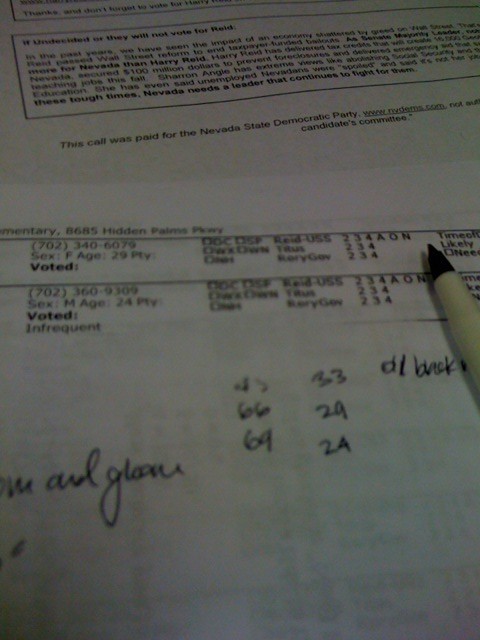

The Reid campaign tracks phonebank results by hand. On paper.

The names and information for about twelve voters are printed on each of the Reid phonebanking sheets. After making a phone call on behalf of “the Democratic party,” we were told to circle whether the voter had supported:

1. Harry Reid as Senator,

2. His son, Rory Reid, for Governor,

3. Dina Titus for Congress.

Some people planed to vote for Harry but not for Rory, so you had to mark a “2” for Harry and a “4” for his son. (Undecideds were a “3.”) If we didn’t get a response because of a busy line or a wrong number, we had to check off one seven tiny boxes ( ‘DC,’ ‘SP,’ ‘WX,’ ‘WN,’ ‘BZ,’ ‘NH’) listed alongside each phone number.

So for insistance, I talked to a Clark County resident who spoke Spanish and intended to vote for Reid but had never heard of his son or Dina Titus. I had to mark this as “2, 3, 3, SP” on my sheet. There’s a bar code next to each voter’s name, so then later campaign workers scan the codes and enter in the data collected.

This was the same method used for the Obama campaign. This sort of data entry takes hours, is easy to mess up, and quickly gets backlogged — thereby keeping people who already voted in the phonebank and house visiting rotation.

At Reid HQ, I made 32 calls in an hour-plus.

* * *

The volunteers seated at the Reid phonebank table were like a diversity brochure come to life: a black lady in her 60s, a young Asian woman, Latino college students, members of the coveted white working class and also an elderly Welshman who had the disposition of a jolly gnome. The campaign staffers are all young, under thirty, and there are a lot of them, on their Bluetooths, in Obama t-shirts and jeans. Two extremely young men came in holding door-to-door canvassing packets. They reported the neighborhoods they canvassed and then have a staffer sign some papers for them.

I chatted with one of the boys. He’s smiley and blushing, wearing skate shoes and t-shirt with distressed, decorative gothic lettering. He’s seventeen years old. “We have to put in ten hours of community service to graduate,” he said. I asked him how it was going door to door. “It was super windy, but it was fun,” he said. We talked about his school’s homecoming and how universally lame homecoming is. Then his ride came to pick him up.

When faced with a voter enthusiasm gap — the kind of dispassion that settles in around a lackluster incumbent in a faltering economy (and, in the case of Harry Reid, a cadaverous temperament) — a campaign’s ability to target infrequent voters and get them to the polls on election day can absolutely change the outcome of a race.

What’s more, Reid has a two-decade legacy of squeaking by in Nevada elections — like in Reid’s congressional bid in 1998, when he beat Republican John Ensign by a few hundred votes.

In most states, getting voters to the polls is a 14-hour operation. For a campaign in Nevada, voting booths are open each day for more than two weeks before the election. So the standards of an effective mobilization campaign are higher in Nevada because there’s a whole other logistic feat to master: tracking people who already voted in order to avoid wasting time and resources. This is usually done by going to precincts and checking the voter rolls. (You’re not allowed to write anything down though, so it’s laborious and inefficient.)

* * *

The Democratic headquarters looks a lot like the way it did in during the 2008 presidential election, with one big difference: no momentum. Given the stakes of the race, it was my opinion that the staffers were moving at a surprisingly sluggish rate. Over the course of the day, they deployed and debrief, over and over, but with food-service style enthusiasm. Two years ago, the Obama campaign captain was a 27-year-old sparkplug from Boston who talked, walked and commanded squadrons of volunteers with Sorkin-style speed and precision. Days before the election, it was all delirium and nerves. When people would get burnt out, he would cheerily remind, “This is History we’re doing! History!”

Most of the staffers today are in front of their laptops clicking back and forth between data entry forms and YouTube. The young man overseeing our phonebank called over a female staffer to show her the infamous “Always Be Closing” speech from Glengarry Glen Ross. In between the snatches of “Hi, I’m calling from the Democratic party,” you could hear Alec Baldwin’s throaty voice over the tiny speakers, berating a small group of sad sack real estate hustlers.

Blake: Let’s talk about something important. Put. That coffee. Down. Coffee’s for closers only. You think I’m fucking with you? I am not fucking with you. I’m here from downtown. I’m here from Mitch and Murray. And I’m here on a mission of mercy. Your name’s Levine? You call yourself a salesman, you son of a bitch?

Dave Moss: I don’t gotta sit here and listen to this shit.

Blake: You certainly don’t pal, ‘cuz the good news is — you’re fired. The bad news is — you’ve got, all of you’ve got just one week to regain your jobs starting with tonight.

I used to watch the same clip with fellow campaign staffers when we were attempting to get healthcare reform passed in the first frigid days of Obama’s presidency. We used to repeat the Mamet-penned soliloquy, in private, before big meetings and rallies to get our energy up (it worked much better than any “Si Se Puede” chant). It allowed us to have the kind of naked aggression and bravado that’s usually absent in squishy, lefty, non profits.

“Ok, I’m over this,” the female staffer muttered, as she shuffled off from her inspirational video session. “I have to go to do data entry.”

Natasha Vargas-Cooper is in Nevada through the election — you can reach her via Twitter.