'The Social Network': The Old Constructing Heroes For The Young

by Matthew Wollin

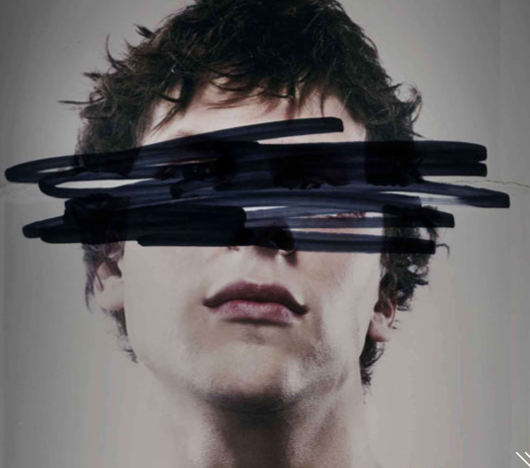

Each day I pass the glossy posters vaunting that actor’s face who I recognize from somewhere as a prettified stand-in for the CEO of that company that’s supposed to be changing the way I think, his visage of slack-jawed moronism a lame-ass stand in for profundity as decided by some group-tested marketing-teamed tautology of whatever it is that passes for brainstorming nowadays, covered in words that purport to represent the names he has been called by his (or my) peers, to be played by earnest, attractive actors who also call up feelings of vague recognition, actors conversing intently with each other in topical settings that show the world I inhabit in roughly the same way that “Jersey Shore” shows the actual Jersey shore, words whose variety and brevity (Punk. Genius. Douchebag.) claim to indicate the strength of emotional response generated by this simulacrum of somebody I have never met and give, at best, a damn about, I feel intensely ticked-off and spurred to action both, to a degree that hits and surpasses the level of guileless eagerness to shell out $12.50 that the film seeks to find in me and so wholly misses, in tandem with my sheer fed-up-ness with the presumption that this is what I most deeply care about, and hand in hand with the suspicion that not only are they missing the point, but that this shit blows.

Yes, I am on Facebook. I am part of the 176% on twentysomethings who exist online, who have friends and post on each other’s walls and have status updates and stuff. Now let’s talk about something else.

The complacency this film assumes that I have grates on me, hard. It’s like a suggestion of what I would find interesting, one that is all the more frustrating for the laziness with which it wasn’t developed. The thought process behind the movie, the one all the way at the back-because I bear no ill will towards Aaron Sorkin or David Fincher (though guys, I thought you were awesome but you have seriously let me down here man) or even Mark Zuckerberg, whose legacy is so far up in the air that my computer-trained eyes can’t even find where in the sky it was flung-is painfully, insultingly apparent: young people are on Facebook. No, young people like Facebook; young people go to see movies about things they like; QED, The Social Network. The sheer and blind underwhelmingness of this idea, its power to cajole some of the cultural power players with greater caché and artistic cred is evident in every frame of the film’s immaculate and preposterous trailer. It is an alluringly simple pitch, almost seductively thoughtless. I cannot blame the people involved. They have careers to support. I try to refrain from placing blame, because I feel guilty about it afterwards.

But has the creation of our own heroes (and villains and villain-heroes) been taken out of our hands entirely? Do we no longer rise to the occasion? Is the premature canonization of someone whose nominal status as a prophet for the young springs almost entirely from the pens and minds of thinkers whose most immediate tie to that generation-no, to me, because this is more than abstract when you’re one of those twentysomethings we hear so much about and happen to have something to say and the wherewithal to know that even if it doesn’t link to Foursquare, sometimes it just doesn’t matter-when their immediate tie is hereditary, is that all there is? I would hazard a “no,” but emphatically: perhaps it is all that has been given to us, but we are better and more complex than that, and if we are only just finding the adamance and defiance that push our talent from sanctioned accomplishment into the realm of getting shit done, it is because only now have we found the thing that we can be against wholly and with every ounce of audacity, with all due respect: this notion of the future. Not so much that we will Facebook and tweet and whatnot (I appreciate a well constructed series of 140 characters as much as the next aspiring intellectual), but that we can be told what defines us. We reserve that right, even if we have not yet used it in full.

If this claim seems overblown, well, there may be some truth in that. There is no blame to be placed, because it is just a movie, after all. No lives will be unmade, no tectonics will shift, just because a shiny cultural product from the world’s leading producer condescends to its audience; that is nothing new. Nothing is to be gained by seeking a foothold for attack when the geography doesn’t permit engagement.

We cannot expect the professionals to be the revolutionaries. Pros (which actors and filmmakers often are) are too dedicated to the thoroughly excellent completion of the task at hand to partake in the extravagant sacrifice of talent that leads to new things. Here perhaps is part of Zuckerberg’s appeal as a deeply fictionalized biographical subject, particularly by a group of seasoned professionalss, one that contains some truth: he seems insistently and alluringly amateur. Amateurs exude in full the inefficiency necessary for invention, while pros tend towards innovation’s efficiency. In the context of people who know exactly where they are headed, the ambiguity and superfluousness that are a part of invention seem deliciously exotic.

Both Sorkin and Fincher are filmmakers whose past work has something of a top-down aesthetic, consisting of sensational pieces of mass entertainment in which their will is always present, and often subtle, elegant, and thoroughly convincing. They deal largely in ideas and moods of their own that find a place in created worlds, rather than finding worlds ripe for the recording. That’s happened here again, but because this time it’s about the now instead of the then, news instead of history, and the usually subtle superimposition mutates into a mesmerizing disconnect between speaker and subject, infusing the story with an epic, overwrought, even Grecian air that feels fascinatingly inappropriate for its subject. They’re calling down from the peaks to all those kids at the bottom who haven’t decided if the mountain’s worth the climb, totally missing the point that this heroic narrative is rendered insufficient by the very thing they purport to understand. It’s old-school marketing meets new-school possibilities: to quote Joey Lucas quoting a French revolutionary, they did their best to figure out where we were headed so that they could lead us there. In classic fashion, they’ve made the guy a hero, when the term doesn’t ring true anymore.

It is perhaps not the responsibility of the young, or their culture, to consciously manifest the values that will lead us forward; that tends towards the canonical in a way that defeats the fundamental inventive impulse. But it is clear enough what we should be against, where we are coming from and what we should leave behind, if not where we are headed. I may see The Social Network. I am not sure if I want to, and depending on how much pocket change I have in October I may find myself in a theater, watching a film that I am sure will be better than I would wish. But still, the question I ask now, heedless of the film’s quality and to spite the notion that it matters: is this the best we’ve got?

Matthew Wollin lives in New York. He has no other pertinent personality traits.