John Edgar Wideman On The Sadness Of Emptiness

Soon after moving to New York in 1995, I was walking down Avenue A one afternoon when a guy with a frown on his face beckoned me over to him. He was a black guy, standing next to a suitcase he’d placed on the curb. “Excuse me,” he said. “But could you hail me a cab?”

I looked out on onto the street, where there were many cabs with their vacancy signs lit up driving past us. I looked back at him puzzled.

“None of them will stop for me.”

I looked at him like was pulling my leg. Because I thought maybe he was.

“Because I’m black,” he said, exasperated, with an unspoken “Duh!”

“Really?” I said. I stepped out into the street and raised my arm. A cab pulled over almost immediately.

“Thanks,” he said, politely. But he was angry. “I’ve been out here ten minutes. I gotta get to the airport.”

“Sure,” I said, stunned. I had heard about this phenomenon on TV and stuff. But I guess I’d never understood it to be so blatantly true. There were really lots of cabs on the street. I stepped aside so he could get to the one that had pulled over. “And, umm,” I stammered some and offered a lame, “Sorry.”

He gave me an expression somewhere in between “Thanks, you’re sweet,” and “You’re an idiot.”

For the next five years, I worked at Vibe magazine with lots of black people, and it became a very regular and accepted thing-whenever a bunch of us would leave the office and to go anywhere together, I would get the cab. We joked about it, Like, What a world. But the joke was always a little sour.

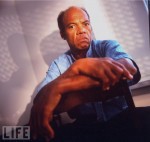

If you missed John Edgar Wideman’s op-ed in yesterday’s Times, about how no one ever takes the empty seat next to him on the train because he’s black, you should read it. It’s really good.

“I admit I look forward to the moment when other passengers, searching for a good seat, or any seat at all on the busiest days, stop anxiously prowling the quiet-car aisle, the moment when they have all settled elsewhere, including the ones who willfully blinded themselves to the open seat beside me or were unconvinced of its availability when they passed by. I savor that precise moment when the train sighs and begins to glide away from Penn or Providence Station, and I’m able to say to myself, with relative assurance, that the vacant place beside me is free, free at last, or at least free until the next station. I can relax, prop open my briefcase or rest papers, snacks or my arm in the unoccupied seat. But the very pleasing moment of anticipation casts a shadow, because I can’t accept the bounty of an extra seat without remembering why it’s empty, without wondering if its emptiness isn’t something quite sad. And quite dangerous, also, if left unexamined.”

Wideman’s novel Philadelphia Fire is really good about this stuff, too. It’s based around the 1985 police bombing of the Move headquarters and is more broadly about blackness and anger and sadness and fucked-upness in America. But it also has the funniest, most-profane rereading of the Tempest you’ll likely find anywhere. And Wideman’s prose is beautiful beautiful. You should pick it up, if you haven’t already read it.