Glenn Beck as America's Professor

by Mike Barthel

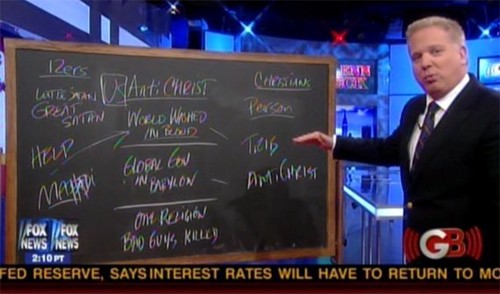

Recently I decided to check in with Glenn Beck. (I do this semi-regularly with all the various cable news talk shows out of a sense of responsibility, though I never last more than about 10 minutes at a stretch.) I was not optimistic. Based on the clips I’d been exposed to by people who don’t like Glenn Beck, I expected a mix between a revival meeting, a Klan rally, and the McCarthy hearings. Instead, I got Glenn in front of a blackboard, lecturing about…Calvin Coolidge.

I found this hilarious. In terms of presidents, it’s like giving a lecture about James Bond focused entirely on George Lazenby. Coolidge lucked into the presidency after Warren G. Harding died (Harding having made the fatal mistake of speaking at the University of Washington), and is primarily remembered for being very quiet. But Beck seemed to love the guy, which struck me as odd given that Coolidge was in office from 1923 to 1929, a period which may have seemed fun at the time but which we would regard today as somewhat misguided in terms of public policy.

A quick visit to Coolidge’s Wikipedia page, however, will tell you why Beck likes him — he’s a prototypical small-government conservative — while also suggesting that Beck’s viewers have made a few alterations to the page; for instance, Coolidge is praised for not including any members of the Klan in his government. (Wow, sure, cookies for everyone!) Nor was this episode an anomaly: Beck is now going after Woodrow Wilson, who’s at least the right target even if Beck’s going after him for the wrong reasons.

Besides the strange choice of subject matter, I was struck by the delivery: a guy who’s trying to advance a populist political agenda was performing an hour-long academic lecture. As someone who has spent his share of time in front of a classroom, it struck me as perhaps not the best way of seizing the attention of a television audience. If that’s all you’ve got, then great, but Beck is clearly adept at producing emotionally compelling arguments through theatrical gestures. What does he get out of posing as a professor?

Well, scholarship has a certain authority, and Beck would like to claim that authority. In the post-civil rights era, Beck’s familiar us-versus-them stance can’t be framed in terms of identity; most of his audience may be white and middle-class and older, but even older middle-class white people would be uncomfortable publicly making the argument that they deserve to be heard because they are older and middle-class and white. Instead, he (and many other media figures on both sides of the spectrum) utilize the stance that their audience deserves to be heard because they’re objectively correct about certain things. They simply know more than other people, the argument implicitly goes, and this knowledge only belongs to a select group. That lets you draw us-versus-them lines without coming off as a bigot. Unless you’re going to turn to mysticism, however, the only place you’re going to locate that kind of elect intellectual authority is in scholarship.

The problem for Beck and others on the right is that they also have a cultural distrust for the institutions that normally produce scholarship, which are a) liberal, b) elite, and c) collectivist. If the conservative worldview finds self-worth in rugged individualism, then the structure of the academy, in which those deemed worthy are allowed to engage in a lengthy apprenticeship to a figure of authority who’s probably an old hippie, isn’t going to work for them. Indeed, Beck’s only college experience is a single theology class at Yale in his mid-30s. Instead, his post-secondary education has come through a program of self-directed learning, pursued largely through book reading; he’s said his curriculum has included works by Alan Dershowitz, Pope John Paul II, Adolf Hitler, Billy Graham, Carl Sagan and Friedrich Nietzsche. (From which he learned, one supposes, that billions and billions of Jewish lawyers can be saved through the power of Jesus Christ, assuming they have a will to power and don’t have any abortions.)

In other words, Beck is taking advantage of the American tradition of the “self-made man.” The phrase itself originates with Frederick Douglass, who applied it both to himself and to consummate Yankee Benjamin Franklin. By framing such an identity as fundamentally American, it transfers the respect we know to give to Jefferson’s much-fetishized yeoman farmer to men of more ephemeral pursuits: teaching yourself and making your own way in the world becomes like building your own house and growing your own food, self-sufficiency as a mark of worth. Of course, both Franklin and Douglass had no option but to be self-taught, given that the public school system did not exist at the time, and Douglass, as a slave, was legally prohibited from learning to read, whereas modern Americans have access to a still pretty great public school system and the best institutions of higher learning the world has to offer. Nevertheless, the romantic image of the self-made man continues to resonate with qualities of individualism and hard work in the American imagination. That’s why the fact that certain tech-industry pioneers (and what-have-you) dropped out of or did not attend college is seen as greater evidence of their genius. This kind of authority fits particularly well with the image Beck’s trying to project: if the knowledge that makes his cause just is accessible to anyone, the movement can’t be elitist, exclusionary or based on identity. At the same time, since exceptional effort is required to acquire the knowledge, possessing it makes his audience special. Sharing this knowledge communicates the idea that those in his audience are creatures of worth. Just as the right believes that anyone can be rich if they try hard enough, so can anyone agree with Glenn Beck if they are willing to put in the work.

The problem with this sort of learning, though, is that there’s no one to tell you if you’re getting it wrong, no one to tell you about the dangers of historical analogies. And even if you do get it wrong, that opposition is easily seen as greater evidence of your own inherent rightness. You’re not misinterpreting evidence; you’re shaking up the establishment! A recent Economist article nicely summarizes the problems with Beck’s method:

If you try to teach yourself history and political science from scratch, you’re likely to draw a lot of shallow and inaccurate conclusions, particularly when you’re the sort of person who’s predisposed to seeing things in terms of white hats and black hats. One role of instructors, particularly at the college level, is to smack down the sweeping generalisations and facile analogies their students tend to make, and try to force them to adopt more rigorous and complicated approaches. But what if you’re surrounded by people who reward you handsomely for making sweeping, slanderous generalisations, both because it delivers ratings and because it’s ideologically helpful?

There’s certainly nothing wrong with not going to college or with being an amateur historian. My father has made a productive second career for himself writing in-depth histories of baseball and/or the Civil War. Doing primary-source research, or just getting out into the world and doing things that don’t require professional certification, are still excellent ways of pursuing the self-made ideal. But for any pursuit that requires an extensive knowledge of what’s come before, the Beck technique of only consulting secondary sources leaves the erstwhile scholar without the ability to critically evaluate which are right and which are wrong, or to understand arguments as elements of a widely-accepted larger narrative rather than as totalizing explanations in and of themselves. For that, the academy, as reviled as it is, is still pretty hard to beat. It’s no accident that the practice of academic work has sprung up in most major world civilizations; it’s a great way not just of producing new knowledge but of passing on existing scholarship as a kind of oral history, as institutional knowledge of what’s worked and what hasn’t. Today, you see this in general exams, a rite of passage when faculty gather to assess whether an aspiring scholar has adequately memorized the body of knowledge pertinent to their field — even though such knowledge is not exactly inaccessible in this digital era. What is being tested is not knowledge, but understanding, the ability to tell an accurate story about what we collectively know.

So some people are actually more qualified than others to have a discussion about what caused the Great Depression. But when Beck argued on-air that Hoover’s depression-causing mistake was backing away from Coolidge’s laissez-faire policies (rather than, say, not allowing the government to pursue more activist strategies), he’s doing so not on the basis of a careful assessment of the facts but because it fits in with his ideological assumptions: laissez-faire economic policies couldn’t have caused the depression, because laissez-faire policies only cause good things. This sort of reasoning is sufficient for politics, but in a more academic context it looks an awful lot like question-begging. Despite the props of learning he employs (blackboards, spectacles, pointers, Socratic dialogue), Beck’s technique brings him closer to the conspiracy theorist than to the scholar. He starts with a conclusion and accumulates a vast reservoir of facts to support that conclusion, even when the conclusion itself is invalid on its face. We all know conspiracy theorists aren’t to be trusted, of course. But by carefully hewing to the performance of the self-made scholar, Beck is able to make his audience feel like they’re learning something new, even when they’re just being told the same old thing.

The big question with Beck, as it is with a lot of figures in the latter-day conservative moment, is this: what is he? Is he evil? Ignorant? Performance art? Were I writing this for Harper’s or the Baffler or something, I would probably have to connect Beck’s dubious presidential scholarship to the right’s attack on American history, in which they’ve invented a religious basis for the nation’s founding (and a divine origin for the Constitution) and exiled morally problematic parts of our past to the cutting room floor, while simultaneously promoting capitalism as a positive historical force. But honestly, I’ve always thought that painting this as a coordinated campaign was an overly generous assessment of human beings’ ability to coordinate their activities. (Especially when those human beings are so dedicated to individualism, you know?) While I’m sure there are a few people with a big-picture view nudging things in a preferred direction, at the local level where these decisions get made, I can’t help but think it’s more due to the eternal human impulse to get everyone else’s view of the world to align with your own.

The conservative guy who comes to a school-board meeting demanding that they not teach evolution just wants everyone to agree with him. As do we all! In terms of motivation, liberals’ demands that the unpleasant parts of American history be taught in schools is no different from conservatives’ insistence that they be expunged: both want the story told as they see it so that children will grow up sympathetic to their view of the world. Of course, liberals have the advantage in this case of wanting things to be revealing, rather than concealing. But that doesn’t make our intentions any nobler, particularly.

And so this is what Beck’s doing with his academic excursions. He’s trying to accumulate enough facts so that the conservative worldview in which he believes can seem plausible once again. After all, it would take a pretty stupid conservative not to question the fundamental aspects of their political beliefs after an arch-conservative, ultra-capitalist Republican president ushered in a massive recession.

But it’s unrealistic to expect them to change their minds; after all, neither liberals nor conservatives change their political beliefs very often. Instead, we just find new ways to justify our ideology, which indicates, I suspect, that our political beliefs are more of a cultural trait than a carefully reasoned view. And that’s fine. I’d just prefer we be honest about it. If politics is something we’re not likely to be rational about, then why sully rationality by association? We can read about the past without needing it to confirm what we think about the present, and we can spin out elaborate accumulations of facts supporting a dubious conclusion without needing the conspiratorial web to be true. Glenn Beck tells a good story; Glenn Beck makes, though he doesn’t intend to, impressive art. The world would just be a better place, I tend to think, if he stuck to novels.

Mike Barthel has written about pop music for a bunch of places, mostly Idolator and Flagpole, and is currently doing so for the Portland Mercury and Color magazine. He continues to have a Tumblr and be a grad student in Seattle.