How Scratch-Off Lottery Tickets Have (Not Yet) Changed My Life

by Beth Boyle Machlan

“Loose Change” or “Amazing Eights”: that’s a one-dollar play with a maximum win of $500-or half of what I owe this month. “Lemon Twist” or a crossword: that’s two dollars to fix my car and kill off one of my Visas. Five dollars buys me a “Black Series 2” or a “Millionaire Madness.” Either one would bring me back to baseline, make me someone who pays her phone bill on time and maybe once a year goes on vacation. A “Platinum Payout” costs ten dollars (eek), but I could both break even and buy a house-not a big one, but that’s okay. Yes, I know, Megamillions costs just a dollar and a dream, but I don’t have time for dreaming. This is a plan-a serious financial plan. One $2 scratch-off lottery ticket is all that lies between me and solvency, and $5 could buy me success.

As far as the world is concerned, I’ve already won the lottery. My children and I are healthy, not hungry or homeless. I have a good job, a loving family and partner and great friends. So it’s easier to ignore the statistics telling me I’m more likely to die in a plane crash or be blown up by a terrorist than I am to win a lottery jackpot. I’m not trying to get ahead so much as catch up, refresh the page. For someone who assigns herself only a 50/50 chance of surviving plane flights anyway, scratch-off lottery cards-magic wands that only work .001% of the time, roll after fat roll of golden tickets that admit the holder to absolutely nowhere-make perfect sense. Hell, education got me into this. Maybe foolishness can get me out.

It helps that I waited until I was 40 to move to New York. My hopes aren’t as high as they used to be, mainly because I know the difference between what I want and what I can actually do. My reasons for coming here are, compared to most people’s, sadly rational; I just wanted to spend less time commuting and more time with my boyfriend and kids. The electric giddiness New York used to elicit in me every time I climbed, blinking, out of Grand Central into a night striped with skyscrapers? Long gone. Now it’s just next in a number of places-Princeton, Portland, Buffalo-where I’ll dream of Being Happy, but I’ll settle for Not Sad. If the city still has magic, it shouldn’t waste that wonder on me.

Besides, I’m not really new here. I was born in Brooklyn in 1970, and my parents moved to Westchester in 1972. Twenty years later, post graduation, I commuted from their house to a marketing job in midtown. I ran away to Maine after seeing a long line of weary people block a seeing-eye dog and his owner from boarding an escalator near the 6 train. (The dog looked frantic, the man resigned.)

Now my brother lives in Riverdale, a stone’s throw from the apartment building where my grandmother died, and I’ve come to Carroll Gardens, the Italian answer to Bay Ridge, where my dad and I were born. I often wonder what my grandparents would say about my brother and me returning to the city they worked so hard to get us out of, but perhaps New York’s most enduring quality is the way it keeps us wanting. The Plaza palace my Eloise self craved at 6 became a 5th Avenue pied-a-terre at 12 (belonging to my friend’s divorced dad), a Soho loft at 16 (school-sponsored gallery crawl), and then a West Village garden apartment at 23 (housesitting). Then I left. By the time I was ready and able to come back, just this summer, people like me wanted Brooklyn brownstones. So that’s what I have-the ground floor of a Brooklyn brownstone, rather, what the broker referred to as a “garden apartment” and my no-fee mother calls a “basement.”

Is living in the basement of your dream house better or worse than not living in it at all? Beats me. These days, I’m way more focused on cleaning up my past than transforming my future. The type of cleaning depends of course on the crime committed; after six years of separation, my divorce is final, I’m up to date on apologies and a recent physical gave the all-clear for all possible cancers and cooties. Just one mess remains, that dark tower of steadily growing debt, which is apparently immune to apologies and antibiotics. Worse, it’s also immune to on-time minimum payments, and (since the bulk is student loans) to bankruptcy. The sad thing is that, other than education, I can’t even remember what I bought, or thought I needed. Nor am I sure when I started running the American Dream in reverse. All I know is that in spite of her upscale upbringing and four degrees from name-brand schools, the Irish girl is back in a Brooklyn basement, overeducated and utterly screwed.

It’s possible to romanticize poverty. It is not possible to romanticize debt. If they could foreclose on my education like a house or a car, I’d happily pack it up, pull out my memories of each and every course-”Tudor and Stuart England,” “East Asian Art”-and leave them stacked neatly at the curb. (“Take my Ph.D.-please!”) Hell, I’d even downgrade, trade in my ivy and the New England Liberal Arts degree for any of your better state schools. But I can’t, and so I’m fucked. The concept of credit is based on a future brighter than the present; it assumes that your ship will come in. I can sit behind Fairway and scan the harbor until my eyeballs dry, but at this point I’m pretty sure none of those boats are mine.

As the Dead said, way more than once, I need a miracle.

* * *

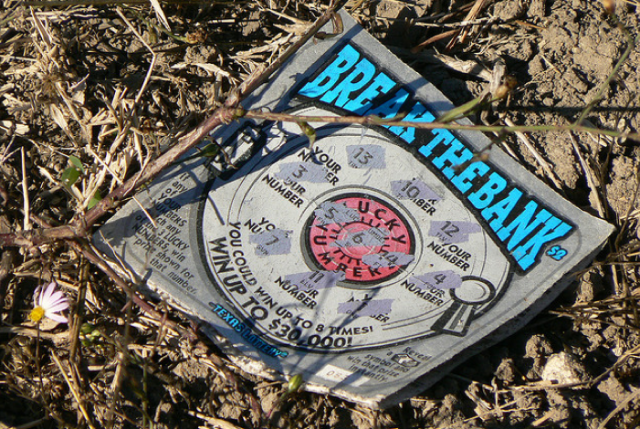

Scratchies are, or purport to be, colorful cardboard game changers, small paper plot twists, mass-produced dei ex machinae. Scratchies offer the chance to jump genres in a matter of minutes, to move you and your family from a dark, damp naturalist novella to an airy four-story romance zoned for P.S. 58. For those of us who play regularly, the numerical near-certainty that we won’t win dick is no match for the allure of “what if?” Hell, everyone who buys a ticket knows they won’t win, but hopes they will. And some of them do. What does it feel like to be the exception, to look down at the card and see match after match, three pots of gold, three tiny flat black piles of cash followed by $25,000, $100,000, ONE MILLION? (I imagine they write that last one out; all the zeros wouldn’t fit on the card.) DDB Inc., the creative team behind the lottery ads, played this angle to great effect. It’s hard to resist the wheedling possibility of “Hey, you never know,” even when you kind of do.

Part of the appeal of scratchies is the illusion of control. There’s a ritual to them. Choose the vendor, choose the ticket, choose the private place to scratch (as when scratching your ass, you don’t want anyone you know to see you), choose the coin with which you’ll dig a tiny pile of gray dust to find, almost always, that you’ve lost again. But that’s the thing-you haven’t lost, not really, because other than pocket change nothing you had is gone. In the odd logic of lottery players, we can only win.

Of course, not all tickets are created equal. To a scratchy addict, playing Megamillions or Powerball seems boring, even fiscally conservative. Yes, the jackpots are bigger, but the chits are thin and colorless and the wait until the drawing interminable-more like planning for retirement (yawn) than playing a game. Scratchers need the right now, the feeling of mastery that comes with choosing and defacing the surface of what could be a whole new world. Spooled like tape or ribbon behind a thin panel of plastic, the scratchies look to me like I imagine cash register candy looks to a hungry, irritable child-an easy panacea-a way to even the score for all the indignities of the last hour, day or decade. There have been bad days when I’ve bought ticket after ticket from the same bright skein, stubborn as a toddler, certain for whatever asinine reason that today, I deserve to win. I once bought thirty dollars’ worth of my favorite $3 game, climbed to a lofty place suitable to what I believed was an epic occasion, and scratched away, my conviction decreasing in direct proportion to the gray shards accumulating in my lap, revealing… nothing. Not even a one-dollar win. That broke me for a week or so, but not for good.

Like most high-functioning addicts, I keep my habit to myself. The few discussions I’ve had with friends who also play reveal an almost universal association between their ticket purchases and their mood. Some buy scratchies when all is well, because they feel lucky. Others play when they feel down, for the cheap hit of serotonin that anticipation provides. Almost all have a ritual; almost all play regularly, regardless of their income, or lack thereof, although their definition of regular varies from “once a month” to “twice a day” (no one confessed to more than that). The one anecdote I heard otherwise may be apocryphal: a statistics professor who bought a single scratchy to use in a lesson on probability ended up winning $20,000. I believe it. And I hate him.

My fantasy of what will happen if I win is, in its own way, as sadly rational as my move to New York. There’s no champagne or limousines or dinner at Per Se, just me at my desk with my checkbook and a stack of bills. I neatly and methodically plow through them, paying each in full.

I imagine calling up Sallie Mae to ask how they prefer I make my final payment, seeing as it’s such a large amount-wire transfer, perhaps? Cashier’s check? I imagine the operator’s initial disbelief, and how my calm demeanor eventually convinces her to take my picture off the Most-Wanted wall and close my account for good. With apologies to Prospero and the magical islands of New York, these mundane moments are the stuff my grownup dreams are made on. Only after visualizing that pile of paper gone do I allow myself less pragmatic fantasies, like a walkthrough of my most recent dream house. It is, of course, a tastefully-renovated brownstone in the historic district just a few blocks from my basement, and offers a gourmet kitchen, a paneled library-ooh, with one of those ladders that runs on a rail!-and a whole bright floor for my daughters. Through the fanlight on the third-floor landing I can see Brooklyn Harbor, where a small boat laden with all my accidents chugs away from my new world. I watch for a while as it beats on against the current, back into the past where it belongs.

Beth Boyle Machlan was born in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn and now lives in Carroll Gardens with her daughters. Her writing about architecture and fiction has appeared in academic journals; her writing about herself has been featured on Nerve.com and The Faster Times. She recently appeared in Representing Segregation: Toward an Aesthetics of Living Jim Crow, and Other Forms of Racial Division. She teaches in the Expository Writing Program at New York University.

Photo from Flickr by Terry Ross.