The Dementia Bonus: Football as Black Servitude

My favorite contribution to the fake motivational poster meme is “Reinstated Slavery.” In deference to those who’ve not seen it, it depicts a white man — a coach, perhaps? — with his arm around the shoulder of a much younger black man, who’s got the netting from a basketball hoop draped loosely around his neck. The white man is smiling gleefully, his eyes on some wonderful prize off in the distance; the young black man is weeping. The caption reads, “Catch yourself a strong one.”

I don’t know much about sports, so I can’t tell you the name of the coach or the player or why they were behaving the way the were in that moment of time (though I imagine they’d won a championship of some sort). What I do know is that the poster succinctly sums up how I’ve come to look at football, boxing and, to a lesser extent, basketball, the older I’ve become: glorified servitude.

Where some see the Super Bowl, I see young black men risking their bodies, minds and futures for the joy and wealth of old white men. Anymore, I don’t just not watch sports; I dislike them in a very visceral way.

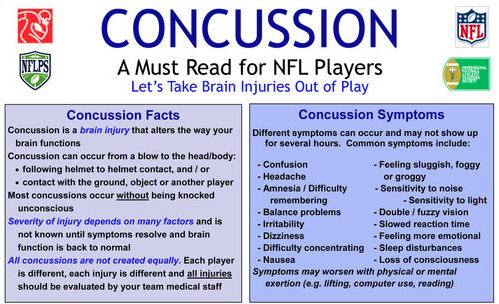

Recently a new poster debuted that now rivals “Reinstated Slavery” for my favorite commentary on modern professional athletics. This one wasn’t a joke. Starting immediately, a poster explaining the severity and symptoms of concussions will be hung in every NFL team’s locker room, probably in a place not easily seen, like an OSHA informational sheet. (It’s in part a project of the CDC, which is expanding its concussion and sports awareness program.)

“Concussion is a brain injury that alters the way your brain functions,” it says. “Concussions and conditions resulting from repeated brain injury can change your life and your family’s life forever.”

Life-changing injuries are what precipitated the poster in the first place. According to a study from last year, NFL players develop dementia and Alzheimer’s at a rate more than five times that of average Americans. The same study showed that “players ages 30 through 49 reported dementia-related diagnoses at a rate of 1.9 percent-19 times the national average of 0.1 percent….”

In others words, many professional football players — almost 70 percent of whom are black — are literally killing their brains, and that’s just the numbers on players in their 30s and 40s. For players over 50, it’s more than 1 in 20.

It’s shocking but actually perfectly sensible considering that football players slam each other into the ground at the end of almost every play. One would never guess it, though, from hearing NFL spokesperson Greg Aiello speak. “[T]here are thousands of retired players who do not have memory problems,” Aiello said when told about how many black men were ruining themselves to enrich him and his bosses. “Memory disorders affect many people who never played football or other sports.” For context here, think of a general sating a bereaved mother with, “There are many people who die of gunshot wounds who have never been to war.”

Lest you think it’s just the PR people who don’t care, the NFL’s legal team is indeed doing its part to contribute to the stonewalling:

On April 30, [2010,] an outside lawyer for the league, Lawrence L. Lamade, wrote a memo to the lead lawyer for the league’s and union’s joint disability plan, Douglas Ell, discrediting connections between football head trauma and cognitive decline. The letter, obtained by The New York Times, explained, “We can point to the current state of uncertainty in scientific and medical understanding” on the subject to deny players’ claims that their neurological impairments are related to football.

Exacerbating its unwillingness to accept that football can cause brain damage is that the NFL isn’t doing everything within its power to prevent head injuries in the first place. As recently as February, helmet-manufacturers were questioning the league’s helmet-testing program, worried that it was dangerously flawed. The tests proved so bad, in fact, that one manufacturer pulled out, with its CEO saying the NFL’s tests are “not deserving of credibility.”

For reasons that are obvious yet difficult to describe, the NFL’s policy of allowing its players to gradually destroy themselves would probably be less offensive were African Americans involved in ways other than just running, jumping and hitting. They aren’t. As of today, there are still no black majority owners in the NFL, and only one who comes close (Reggie Fowler owns 40 percent of the Minnesota Vikings). Out of 32, only six of the league’s head coaches are African American, a dearth that may be part of why blacks don’t even watch the NFL. According to an ABC study, less than 13 percent of the league’s viewership is black. Football fans are primarily white and relatively wealthy, earning $55,000 annually on average. 40 percent are over the age of 50. “Football has demographics that baseball would kill for,” said one CNN analyst, who, were he more direct, would have said, “White guys with hefty disposable incomes watch football.”

Maybe it’s a fair trade — black kids losing the ability to remember their mother’s name in exchange for a decade of big checks and fame amongst middle-aged white men. What’s not fair by any reasonable metric is what comes next, when players retire. Although the NFL recently started a fund that will give ex-players with dementia $50,000 a year for medical treatment, it’s also installed a byzantine bureaucracy between the patients and that money. Brent Boyd, a former Vikings lineman who now suffers from dizziness and chronic headaches, has been deemed ineligible for funds multiple times by league doctors, who say that one of his major on-field concussions “could not organically be responsible for all or even a major portion” of his symptoms.

Without the dementia bonus, the average NFL pension payments, which kick in at age 55, are hardly enough to cover a person’s living expenses and specialty medical care. As of 2006, a 10-year veteran who retired in 1998 would receive about $51,000 annually.

Boxing, which drops the niceties of football and lets minorities and poor whites pound each other’s heads sans helmets, sometimes until someone dies, has no nationwide pension plan at all. The assumption certainly being that all pugilists develop significant financial acumen while hitting the heavy bag for hours on end.

For a stark contrast, consider Major League Baseball, a sport that’s about 60 percent white and eight percent black. Bolstered by a strong player’s union, the MLB has a pension plan that dwarfs that of the NFL, despite the fact that most baseball players rarely hit the ball, let alone each other. Any player who gives just 43 days of service to the MLB is guaranteed $34,000 in pension benefits-just one day as a member of an active roster qualifies him for comprehensive medical coverage. Beyond that, a major-leaguer with at least 10 years under his belt is set to receive $100,000 per year at age 62.

Then there’s the NHL, a vastly, strikingly white organization. While the average NHL pension payment is about the same as the NFL’s, full benefits begin an entire decade earlier than they do for football players. What’s more, NHL veterans who play at least 400 games — about five seasons — are also recipients of a lump sum payout of around $250,000 when they reach 55.

Though the NHL and MLB take care of their players a little and a lot more than the NFL, respectively, both organizations make less in yearly revenues — the NHL about $4 billion less.

It’s all indefensible and disgusting and sad, but perhaps the sickest twist in America’s black-on-black violence as sport is how everyone reacts when our vaunted, dark-skinned gladiators explore bloodshed and aggression off the field, or outside of the ring. Vegas takes bets on when boxers will be knocked unconscious and football fans cheer when they think one man’s hit another hard enough to cause paralysis, yet it’s incomprehensible — inhuman, even — when Michael Vick makes dogs fight for his amusement when he’s not fighting for other people’s amusement. Imagine Mike Tyson’s surprise at how differently witnesses reacted when he wasn’t knocking a man’s teeth out in Madison Square Garden, but some $500-a-bottle nightclub in Manhattan. “You animal!” they must have screamed. “What makes you think it’s OK to punch someone?”

When I was growing up, I had a friend named Joey whose father, Rocco, was a beach ball of an Italian from northern New Jersey. Rocco was always tremendously affable whenever I saw him, being sure to ask me how my parents were and telling me I looked great, all in a charming, gravelly, thickly accented baritone. This warmth never surprised me until years later, when another friend told me that Rocco had a strange habit that emerged whenever he watched the NFL. When black players scored a touchdown and celebrated in the end zone, Rocco would shout at the television, as if he had Tourrette’s. “Do the nigger dance,” he’d yell. “Do the nigger dance.”

Cord Jefferson also writes at The Root.