Scenes From An American Oil Spill

by Suzannah Evans

A few weeks ago, I was on a boat in Barataria Bay off Louisiana’s Grand Isle, touring mangrove islands encircled by orange and white booms. The mangroves brimmed with roosting pelicans with their cottonball chicks and roseate spoonbills turned from pink to beige by a thin film of oil. A local Fox field reporter asked if she could see an oiled bird rescue-the avatars of the crisis. But the breeding colony didn’t have birds that were oily enough for removal, so the Fish and Wildlife Service was just taking media out on motorboats for an educational tour.

One of my boatmates was Alan S. Chin, an experienced photojournalist whose work in Kosovo earned him Pulitzer nominations in 1999 and 2000. Since then, he’s been embedded in Iraq and Afghanistan multiple times, but he told me that photographing the oil disaster has been one of the most difficult jobs he’d ever done. In conflict, there are immediate visual stories with blood and shoes and twisted metal. The creeping oil spill has been more evasive.

There have been a few memorable images: the Jerry Bruckheimer-esque burning rig, the grainy spillcam and the oiled pelicans, which started cropping up in photos a full six weeks after the Deepwater Horizon exploded, providing a gut-punch visual that seemed to finally define the crisis. But unlike the Exxon Valdez spill, in a finite area with a finite amount of oil conveniently located on the surface and near the shore, the scale of the Gulf disaster is difficult to convey. The changes are in the chemistry of the water. The livelihoods of the people who live on the Gulf will slip away as quietly as the tide.

I called Chin up after our on-the-water meeting, and he agreed to share some of his images with the Awl and talk about the unique challenges of depicting the disaster. As the media storyline tips toward talk of the “disappearing” oil slick, he emphasized the less perceptible effects of the disaster that even his experienced lens struggled to capture.

Oil is burned off from the Deepwater Horizon site. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“I had covered New Orleans and the surrounding region since Hurricane Katrina. I went down there for Mardi Gras, and it was really the first time in four years I had gone to New Orleans, not to photograph the after-effects of Katrina but really just to see my friends and to have a good time. It was really the first time in all these years that it felt like the city was back to a real city with a real life. The Saints had just won the Super Bowl, and there was a good feeling in town. And I really finally felt that my project, which I want to publish as a book on New Orleans, Louisiana and Mississippi during and after Katrina, was finished. So I’m feeling good about it, and two weeks later, the shit hits the fan again with this oil spill. And then I felt, well, how do you photograph this? It’s just the most important breaking news story in this country right now and you know that it’s not going to be a fast one; this wasn’t a one-day story, or even a one-week or one-month story.”

At the Deepwater Horizon spill site. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“This is something that’s going to go on for months and the aftereffects are going to go on for years, even decades. So how do you get at something like this? And of course we saw those pictures of the pelicans covered with oil. You can spend time with fishermen and shrimpers, and other people who live on the coast, or even the people who work in the oil industry, whose lives are going to be affected, they’re going to lose income, they’re going to lose their tradition, they’re going to lose their livelihood, you can do all that. You can do what we did on the boat and helicopter, you can try to look at the actual thing itself in terms of ‘Okay, here’s the oil. Here’s the oil on fire.’”

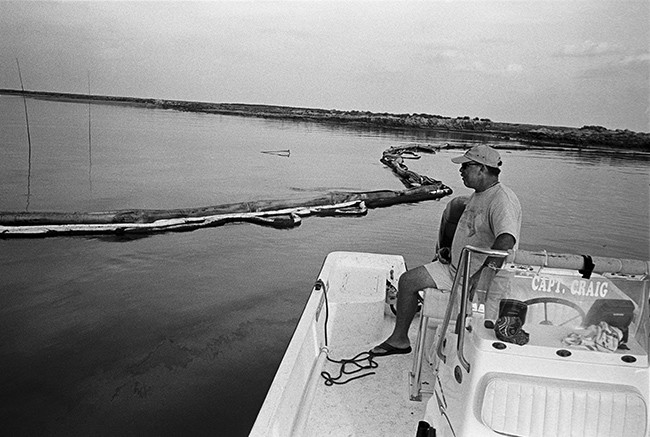

Absorbent booms tangled up near Grand Isle, La. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“And here’s the booms trying to protect these islands, which to me-I didn’t really want to say it in front of those Coast Guard and Fish and Wildlife guys-but to me, it really felt like putting a condom on a fire hydrant. It’s theater.”

A bird rescue crew checks out one of the breeding mangroves. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“But even with documenting all of that, I don’t think any of it really gets the heart of this story, because what makes this oil spill bad, ultimately, isn’t that some birds got covered in oil and died, isn’t that the coastline gets screwed up for a while. The oil is bad because of what it is. It’s a chemical. When you photograph a war, or a catastrophe like Katrina, the damage is evident. Buildings burn. Bodies are in the streets. We know exactly what the impact of this is, right? The levee breaks and a whole neighborhood is wiped out. And you can see it. “

A Coast Guard member. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“I think with the oil spill we can see effect, but the true cause, the actual, biological and physical and scientific reason, is not easy to see. In fact, it’s impossible to see.”

Pelican, Grand Isle, La. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“I could take a pelican, and I could dip him in chocolate, and it would look the same. I don’t think we can really get at the heart of just how awful it is and how much of an impact this will have.”

The more vital wildlife areas are protected by “soft” absorbent white booms as well as “hard” orange inflatable booms. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“I feel that the limitations to access are a little bit subtle, too. Like, for example, the day we went out on that boat. They were happy to show us certain things. But, you know, they were not going to take us to the worst-affected areas.”

Coast Guard air crew on board aircraft flying over the spill site. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“I’ve been in Iraq two times, I was in Afghanistan three times, I covered the Balkan wars in Bosnia, also Israel/Palestine. [The oil disaster is] very different. When you cover conflict, everything, in a way, is easy. It’s horrible, and it’s criminal, but it’s visible, right? Here, it’s slow, and it’s almost invisible except for maybe these couple telling things. This is really a narrative story of long term. It’s going to be 10 years or 20 years. It may be 60 years.”

National Guard helicopters drop 3000-lb. sandbags to build up an artificial berm. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“As long as we’re a great power, these things are going to happen. Because we’re still going to pursue oil drilling even if we do it in a much more responsible way. We’re still going to get involved in foreign wars, we’re still going to have natural disasters like Katrina. I’m a member of the semi-mainstream media, or maybe not so mainstream, I don’t even know what that means-I think we’re actually doing our jobs. I think the problem is reaching the audience. Not that people aren’t doing the right reporting and the right photography and filming and so on. I think we are. I think we’re out there and we are covering these stories and with some intelligence and sensitivity. The problem is getting it out into the world in a way that is effective and that is where I don’t know how to answer that question.”

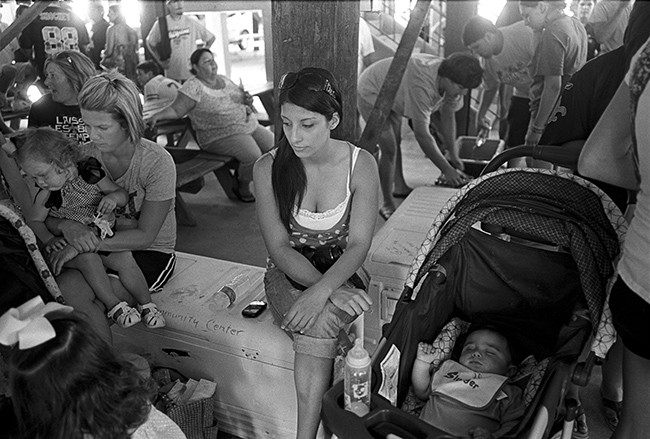

Residents waiting for New Orleans Saints players as part of a morale-boosting event in Grand Isle, La., which was devastated by the spill. [ALAN CHIN/facingchange.org]

“There’s this other project called ‘Facing Change: Documenting America’ which is a group of us, a collective of photographers who have formed a nonprofit. We were inspired by what the Farm Security Administration they did in the 1930s, like the Dorothy Lange picture of the migrant mother. Those were the iconic images of the Great Depression. We live in a very different media world and a different society than they did in the 1930s, but we aspire to that kind of project. We think it’s extremely important to create a historical record of this time because-for all the reasons I’ve just been talking about-I think the time we’re living in now is as critical as what this nation went through in the ‘30s. Maybe it’s not a Great Depression, but it’s damn critical.”

Alan S. Chin has covered conflicts in Iraq, the ex-Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and the Middle East. His work has twice been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

Suzannah Evans is an editor for a nonprofit in Washington, D.C. She recently resurrected her Tumblr after a three-year hiatus.