Footnotes of Mad Men: The Youth Machine and Godzilla Handjobs

by Natasha Vargas-Cooper

The main ingredients of American counterculture formation all guest-starred in last night’s “Mad Men” episode: abortion, Berkeley, Vietnam and, most ominously: young people. The ‘youthquake’ is not just an explosive population boom, it’s when, supposedly, teenagers and college students seized control of culture from adults. At the very least, they seized control of the consumer goods market. Beginning around the 1920s, a common theme in advertising was to offer a return to youth and vitality (and relevance in the towering industrial age) through consumer goods. Oatmeal, face creams, sodas all made mention of youth in their slogans. But that was selling youth to the aging. In the 60s, the symbolic role that youth played in American culture-honesty to self, renewal, rejection of ancient values-became a driving market force. This notion was really that becoming an adult meant participating in consumer culture. This is perhaps the most loathsome legacy of the Boomer’s ascent to cultural dominance: the perpetual teenage mentality of rebellion through buying things.

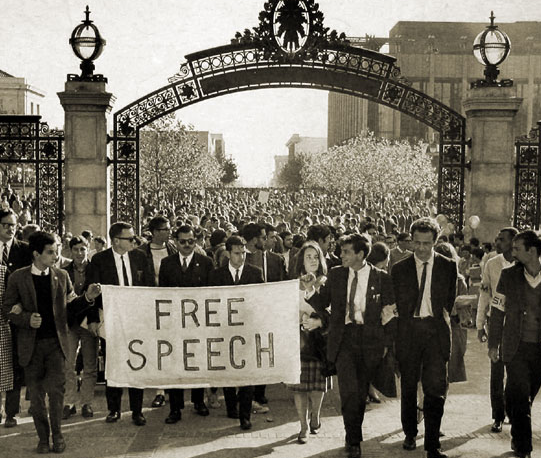

• The dogma of parental authority was being slowly dismantled through the early 60s and was eventually bulldozed, thanks in part to the protest movement coming from Don’s Long Beach Lolita’s college. Throughout much of 1963, Berkeley students were actively involved in mass protests against banks, grocers and city government for racial discrimination taking place in nearby Oakland-a suburb that played host to a tiny affluent population and a large, mostly black population mired in grinding poverty. After enough business owners and politicians complained to the school’s administration for their unruly and cantankerous student body, the Berkeley dean took action: student political groups were banned from using the school’s plaza to solicit support for “off campus political and social action.” This sparked giant and immediate demonstrations on the plaza, in front of the administration’s building and eventually inside of the dean’s office. In the melee, a charismatic young man with wild hair and a riveting manner became the de facto leader of the protests when he gave this impromptu speech in late 1964, before leading students into halls of the dean’s office for a sit-in.

There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.

• Joan has had abortions or, as she refers to them “procedures,” but now Joanie would like the option to have a baby. Though her doctor has proven himself to be a condescending finger-wagger when it comes to ladies and family planning (remember in season one, when he warned Peggy not to become the “town pump” if he gave her the pill?), he was willing to put not just his medical license on the line but possibly his own freedom, as he once performed an abortion for Joan. Aborting pregnancies in 1964 in New York, depending on the length of pregnancy, could mean jail time for physicians.

If Joan were to find herself with an unwanted pregnancy-as a married lady-she could have put in application to the Mount Sinai abortion panel in New York. She would have needed the recommendation of a psychiatrist that her life would be in danger if she were to become pregnant-due to threats of suicide or a promise utter mental collapse. Then two consultants would have to be consulted and one would have to testify before the abortion panel. 1 out of 4 abortions approved by the panel in 1958 were given to married women. It wasn’t until 1965 that abortion reform would begin to loosen state laws around performing legal abortions for rape and incest victims.

• Lane Pryce with his lower-upper class accent and prim disposition! He makes me want to salute the Union Jack every time he comes on screen. (Or, apparently, off-screen.) He was finally on camera long enough to get a look at that distinctly continental apparel. The English suit that Pryce dons is heavy even for winter, nothing like the less-elaborate suits of Wall Street in the 60s, or the slanted pocket Italian suit with the barely-there-lapels. Pryce’s suit is purebred English: with vest, tie with a full Windsor knot, in muted browns, grays, and blues-if you want to get cheeky you could go cream-a white pocket square (no patterns), with the shirt quite starchy with hard collar. (He’s an interesting contrast as Don’s ties are getting ever-thinner.) And on the jacket, beautiful buttonholes. As Oscar Wilde wrote, “A really well made buttonhole is the only link between art and nature.” An Englishman’s business style rested upon the idea that through conformity to tradition there is dignity.

You can always find more footnotes by Natasha Vargas-Cooper right here, or, you know, you can get a whole book of ‘em.